After Adolf Hitler became chancellor in January 1933, the public for several months was under the illusion that the situation in the country could be reversed. By March, however, the means of combating the dictatorship within the Reich were virtually exhausted. Those who disagreed with the regime hurriedly fled abroad, mainly to France, Austria and Czechoslovakia. They left Germany not only because their lives were threatened, but also because they wanted nothing to do with the crimes. Anti-Fascist emigrants were not welcomed everywhere abroad. They were interned in special camps, interrogated, arrested, forbidden to work and deported if they had no means of subsistence. Nevertheless, there were well-known anti-fascists who were greeted more favorably – such as the previously apolitical writer Thomas Mann. In exile, he effectively became the voice of emigration, a constant reminder of a different Germany.

Content

Early signals for political refugees

Everybody out

Emigration map

People without citizenship and language

Emigrant leader

The place of a different Germany in the world

Early signals for political refugees

The humiliating provisions of the Treaty of Versailles were considered excessive not only in Germany, but also in other European countries. When Hitler moved to directly violate them (for example, by creating an army and sending troops to the demilitarized Rhineland), other countries preferred to ignore his activity for a long time. France was experiencing an internal political crisis, Britain did not want to get involved in another war on the continent, and the USSR was seen by all as an even bigger threat. Without collusion, all countries adhered to the policy of appeasement; in order to avoid provoking an even greater aggression they made concessions to the aggressor. The mass exodus of political refugees from the Third Reich was long regarded from the outside as a whim of a spoilt public. The emigrants recounted the regime's crimes and warned they would eventually become even greater, but they were not listened to until 1939, when Hitler's Germany attacked Poland at the dawning of the first day of September under the pretext of protecting oppressed Germans.

The mass exodus of political refugees from the Third Reich seemed like a whim of a spoiled public

However, Hitler's regime was not born in 1939; its formation had been long and gradual. At the end of February 1933, a month after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor, the Reichstag fire served tas a pretext for the terror launched against the left-wing forces. The day after the fire, the Reich president Paul von Hindenburg issued two decrees: “On the Protection of the People and the State” and “Against Betrayal of the German People and the Intrigues of the Traitors of the Fatherland”. Both markedly restricted the rights and freedoms of citizens, effectively unleashing political persecution. On the evening of 9 March 1933, the swastika flag was hoisted on the Town Hall tower of Marienplatz in Munich as a symbol of the National Socialists' seizure of power. The last free sessions of the Reichstag were also held in March - they adopted the Emergency Powers Act, which definitively transferred power to the Nazis. Bertolt Brecht wrote:

“The first country Hitler conquered was Germany; the first nation he oppressed was the German people. It is wrong to say that all German literature went into exile. It would be better to say that the German people were exiled.”

During 1933, more than 53,000 citizens left the country, of whom only 37,000 were Jews. The rest left because, as Klaus Mann wrote, “they could not breathe the air in Nazi Germany”. Thus, for example, Bertolt Brecht, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, René Schickele, Oskar Graf, Georg Kaiser, Leonhard Frank, Johannes Becher, Fritz von Unruh, Ludwig Renn and Gustav Regler had no Jewish roots. However, some of them - Heinrich Mann, Brecht, Becher, Remarque - were threatened based on their political beliefs. The exodus of German intellectuals was also a moral choice: emigrants did not want to become accomplices to the crimes of the regime. The departure peaked in the two weeks between March 15th and March 30th. The majority fled illegally, in a hurry, risking their lives, without a valid passport, without money, heading nowhere. In all, during the period from 1933 to the fall of the Third Reich on May 8, 1945, about 500,000 people emigrated from Germany.

Hitler at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Reichsautobahn in Frankfurt am Main sueddeutsche.de

Everybody out

Many intellectuals - whose lives we usually know in more detail from memoirs, preserved correspondence and documents - were for various reasons outside Germany in January 1933. The writer Thomas Mann lectured abroad, the actor Fritz Kortner toured with a theatre company, the composer Hans Eisler and the writer Oskar Graf were visiting Austria, and the poet Walter Hasenclever and the journalist Josef Roth were visiting France. They had the opportunity to remain in emigration at once. But many returned even after Hitler came to power: it still seemed that no major catastrophe had occurred in German political life.

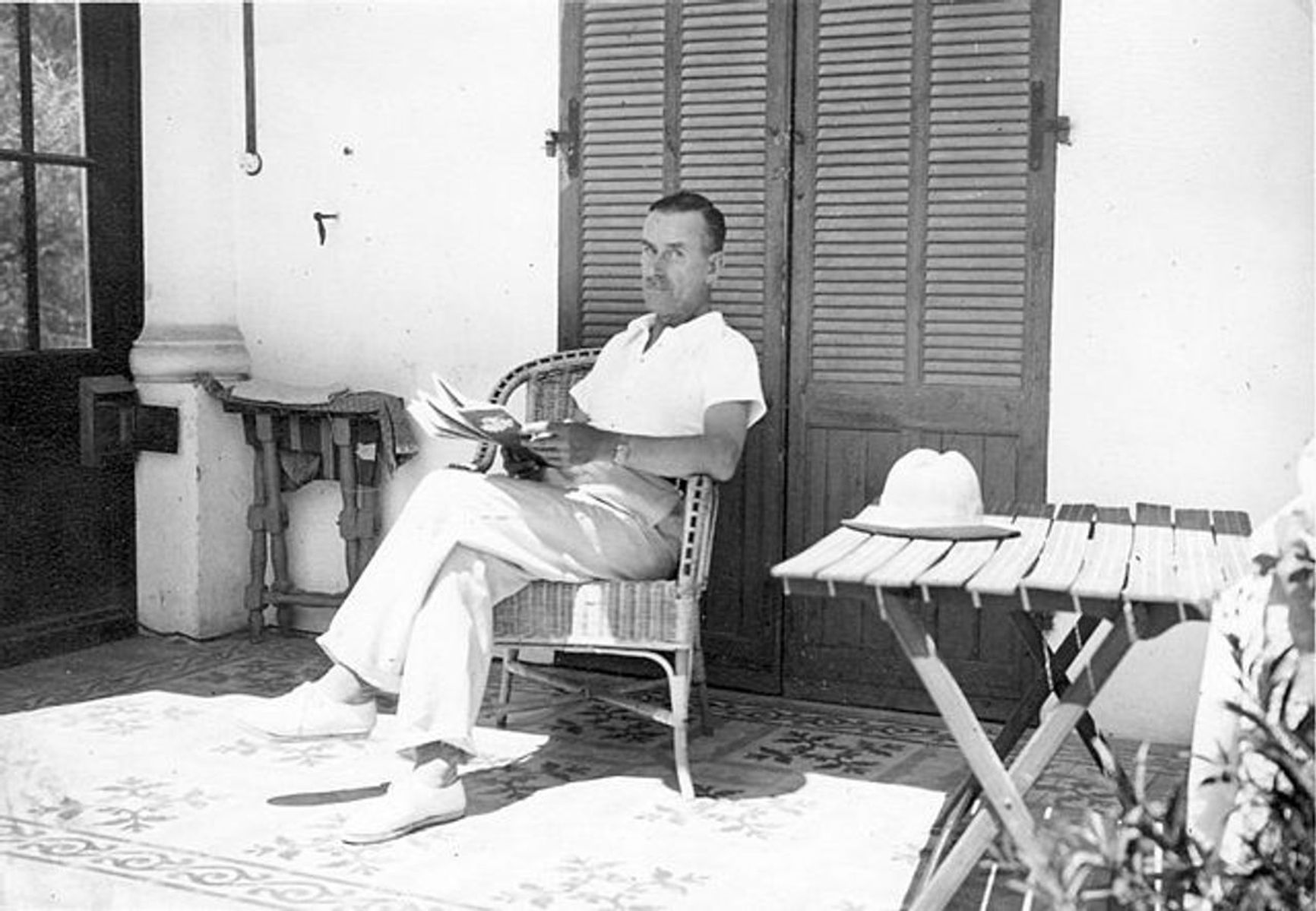

Thomas Mann at his villa in Sanary-sur-Mer in 1933 wikimedia.org

Fritz Kortner, even considering his Jewish background and the threat associated with it, returned to Berlin after his tour ended. When the writer Leonhard Frank asked about the reason for his return, Kortner replied:

“Because they speak English there, because there are no cafes or bars like ours, because I can't just meet you and others, because my mouth is set up to speak German and my head to read German books, because I have no friends there.”

Kortner did later leave and did not return until December 21, 1947.

Klaus Mann, Thomas Mann's son, said that he had called his father and hinted veiledly he could not return to Germany - saying that the weather was bad in Munich and it would be better to stay in Switzerland a little longer. Thomas Mann lightly parried that the weather was no better in Arosa, Switzerland. Klaus insisted and asked for some time to get his Munich house in order. When this did not work either, the younger Mann threw caution to the wind and directly asked his father to stay in Switzerland because of the Nazis. Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann's brother, and also a writer, initially refused to go to France as well: he was confident that the situation would not worsen.

At first, leaving Germany was not much of a problem, especially for the residents of Berlin. The writer Robert Neumann left the capital as soon as Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor, followed by the playwright Wilhelm Herzog and the theatre critic Alfred Kerr, who had fled the country before the end of February. Already after the Reichstag fire, government control became stricter. The Nazis monitored those suspected of the intent to leave - they checked their bank accounts and watched the trains. Anyone who travelled abroad was questioned. The Nazi jurisdiction distinguished, albeit confusingly, between two types of emigrants: racial refugees (they were generally allowed to leave) and political refugees (they were allowed to leave less willingly). Most the latter were ethnic Germans.

A visa was required to travel abroad. Those wishing to emigrate had to pretend to be mere tourists or leave Germany illegally. Publisher Wieland Herzfelde pretended to be seeing his wife off on a train. However, as soon as the train pulled away, he jumped into the carriage. The publicist Alfred Kantorovich left for Davos based on a medical certificate, supposedly to treat his lungs. People also crossed the border in large groups using fake passports. The writer Fritz Erpenbeck disguised himself as a music hall performer. The politician Friedrich Wolf took advantage of his stay in the Alps to cross the border on skis. Social Democrat leader Otto Wels also crossed the border in mountaineering gear. Naturally, those who chose the “tourist” option were not allowed to take a lot of stuff with them – bulky luggage attracted attention. Many had to leave their families behind in order not to arouse suspicion.

On 1 January 1934, the visa regime was abolished. The relaxation was not a sign of leniency on the part of the Nazi government. It simply stopped fearing the opposition - the terror had eliminated it. In addition, Jewish emigration from 1934 to 1935 was seen in a different light: the Nazis sought deals with Zionist organizations to facilitate it. However, conditions for emigration from 1933 to 1940 deteriorated rapidly. Late emigrants could take only 40 marks instead of the previous 1200, and the total value of assets that could be taken abroad was reduced from 200,000 marks to 50,000. Considering that emigrants often had nowhere to work in their new country of residence, such restrictions in themselves discouraged departures.

Emigration map

In 1933, Germany bordered on ten countries. In the early weeks of Nazism, it was quite easy to cross any of the borders. France, Austria and Czechoslovakia were considered the preferred destinations for German exiles, not only because it was easier to flee to nearby countries, but also because exiles wanted to stay close to German borders in case the regime fell and they had a chance to return. Many were waiting for it to be over. In his poem “Thoughts on the Duration of Exile”, Brecht expressed the emigrant illusion of a speedy return that was common at the time:

“No pictures on the wall; why bother? You'll be home soon. You live out of boxes, renting by the day. Tomorrow, that's when it will be, tomorrow.”

Naturally, this did not happen. The exile, which, it seemed, would last a week, a month at most, stretched into long years of painful waiting.

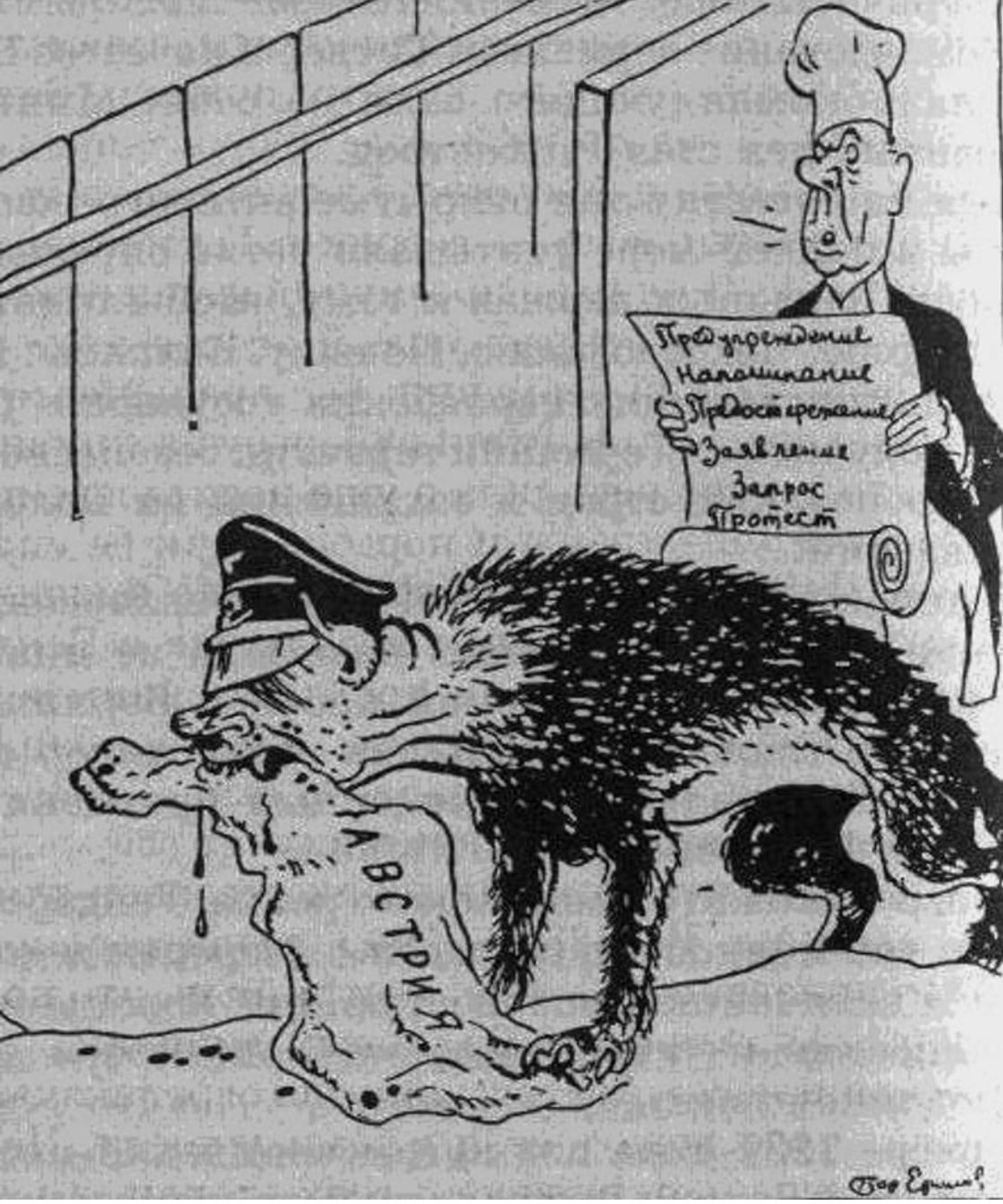

Brecht said that emigrants ended up “changing countries more often than shoes”. In 1933, it seemed to many that departure was only a forced short-term measure, and that the Nazi regime would not last. But by 1939 it was clear that Germany’s successes were consolidating the power of Hitler and his allies. The Saar plebiscite, the annexation of Austria, the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands, the fall of France - the Reich's rapid expansion into neighboring countries drove emigrants further and further away from the country's borders. They were forced to go to England, to America, to the Soviet Union. Despite some similarities, the conditions on which each country accepted immigrants are worth examining separately.

Soviet cartoon mocking public reaction to the Anschluss of Austria geomap.com.

Czechoslovakia

No visa or special permit was required for German or Jewish refugees to enter Czechoslovakia. They were allowed to remain in the country with or without a valid passport, but without the possibility of seeking work. In 1933, the Czechoslovak National Committee for Refugees from Germany was established. It assisted refugees, checked the reasons for their exile, and gathered information about Nazi terror. If it was determined that an emigrant could be considered a genuine fugitive from Nazism, he was issued documents that, while not giving him the actual right to settle in the country, provided him with legal protection. Czechoslovakia was regarded as a loyal, benevolent country for those fleeing from Germany.

Austria

The choice of Austria as a place for voluntary exile is fairly easy to explain: a country with the same language, with a familiar culture, which many of the emigrants had visited (for example, German journalists often wrote for the Austrian press at the time), where they did not feel like strangers and where they were likely to have friends. Moreover, in 1932-1933, neither visas nor permits were required for travel between Germany and Austria. German citizens could live there as long as they wanted. From 1932, Austria also entered a phase in which democracy and freedom were systematically restricted (on March 8, 1933, Chancellor Dollfuss forbade public meetings and demonstrations), and sympathies for Nazism grew within the country. On April 10, 1938, Austria held a referendum on the Anschluss with Germany.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands was considered to be a country relatively favorable towards anti-fascist emigrants. No visas were required for citizens of Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. Refugees were allowed in without a passport. Despite strict rules regarding work permits, the Dutch authorities could grant exiles the right to practice their profession if they considered them useful to the country. German-speaking authors could find not only readers but also publishers in the Netherlands: publishing newspapers or books was not considered a political activity, so they were freely printed and distributed. Allert de Lange and Emanuel Querido opened large publishing houses for German literature in exile there.

Border control sent back anyone who could not prove sufficient financial means, but entry was still allowed if a return to Germany might pose a risk. In 1938 alone, more than 7,000 political refugees were registered with the Dutch police. The actual number was much higher.

The UK

Britain was suffering from an economic crisis and unemployment and was not very keen to accept migrants. By 1937 about 4,500 refugees had arrived in the country. After 1938, when Austria and Czechoslovakia were occupied, Britain changed its migration policy to a more loyal one.

With Britain's declaration of war, the situation for emigrants in the country deteriorated. As in France, refugees were placed in special camps. Stefan Zweig wrote:

“Again, I had dropped a rung lower, within an hour I was no longer merely a stranger in the land but an “enemy alien,’’ a hostile foreigner <…>. For was a more absurd situation imaginable than for a man in a strange land to be compulsorily aligned—solely on the ground of a faded birth certificate—with a Germany that had long ago expelled him because his race and ideas branded him as anti-German.”

German and Austrian refugees in Britain were divided into three categories. Group A was immediately interned, group C was accepted as refugees on racial grounds or as anti-fascists, and group B was left in temporary freedom. They were divided into groups after being questioned by a special committee - to find out about their links to the German government, opportunities for espionage and personal relationships.

Switzerland

Switzerland's policy towards emigrants was quite strict. The laws governing asylum there allowed those without citizenship or documentation to enter. However, provisions added between 1933 and 1938 under the pressure of the economic crisis limited the possibility of any benefits to be derived from that privilege. Entry to Switzerland was denied for a variety of reasons, such as lack of means. After 1933, those emigrants whose “customs” were too different from Swiss ones were denied entry more frequently. That restriction was particularly applicable to Jews.

At least more than 2,000 refugees from Germany were denied permission to cross the French border (which was used more often than the German-Swiss border; it was virtually impossible to get out of the country after the tightening of the regime). Anyone who risked disrupting Switzerland's relations with its neighbors was refused entry. Afraid of being deprived of German coal, Switzerland paralyzed all anti-fascist activity on its territory. Fascist Italy and Portugal often treated German emigrants more humanely than liberal Switzerland, which handed over illegal immigrants to the Gestapo. If a refugee was caught doing even a tiny amount of work, he got deported. However, if he suddenly ended up without means, he was also deported.

Of course, both in Switzerland and in other countries, migrants of some renown were treated very differently. Most often they received a warm and cordial welcome. In Switzerland, for example, Thomas Mann and his Nobel Prize were of course patronized.

The USSR

According to the 1925 Constitution (Article 12), the USSR granted the right of asylum to all those who were forced to leave their countries because of their political or religious views. In practice, this right was granted to German emigrants very sparingly, and from 1936 only those in danger of being killed were allowed into the Soviet Union. The Eastern direction, that is Moscow, was most often chosen by communists - they were readily given entry visas.

Asylum, however, did not always guarantee safety: after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, the NKVD and the Gestapo held a series of conferences aimed at increasing cooperation. Formally, the conferences were used to discuss the exchange of prisoners and internees, but the NKVD also began handing over to the Gestapo antifascists who had fled Germany. There are well known stories of the return of Ernst Fabisch (in 1934 he fled to Czechoslovakia, then to the USSR, worked in the construction of power plants, and was deported to the Reich in 1938), Max Zucker (deported in 1939), Margareta Buber Neumann (deported in 1940), Josef Burger (deported in 1940). Prior to the outbreak of the war, the NKVD gave up several hundred of its former citizens to Germany.

After the attack of Hitler's Germany, the Soviet government actively subsidized anti-fascist movements abroad – it gave emigrants the opportunity to publish their works and sent food parcels. Soviet publishing houses published up to 250 books a year in German, and theaters encouraged productions of German playwrights.

France

People chose France for its proximity to the Reich, its more or less loyal policy toward emigrants, and its reputation as a welcoming country. However, the economic situation there was of great concern to the government - the influx of refugees could exacerbate the crisis. In addition, the reaction of the right-wing press had to be taken into account. From 1933 to 1939, French politics evolved from relative tolerance to stiff rejection. Emigrants became victims of growing xenophobia. Politicians openly said that France was “interested in keeping 100 to 150 major intellectuals as scientists or chemists” and that the rest should be expelled from the country.

The USA

Between 1931 and 1940, 114,000 Germans and thousands of Austrians moved to the United States. The day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt suspended naturalization procedures for Italian, German, and Japanese immigrants, required them to register, limited their mobility, and prohibited them from owning items that could be used for sabotage, like cameras and shortwave radios. The U.S. government interned nearly 11,000 German citizens between 1940 and 1948. Despite the number of emigrants who found asylum here, the United States did not make a sizable dent in the history of German emigration politically. Primarily because Americans tended to deny visas to Communists, the most politically active elements. Remoteness from Europe and a sense of powerlessness in the face of events there only contributed to abstention from political activity.

With varying degrees of relaxation, aversion to migrants was characteristic of all countries. The countries were willing to accept refugees in general, but the scale and intensity of the influx forced many governments to reconsider. The historian Golo Mann, son of Thomas Mann, wrote

“Hitler's regime was not loved, but those Germans who rejected Hitler's rule and protested against it were disliked more. Lack of referral to the relevant authorities, lack of a valid passport always aroused suspicion. So often we heard the same questions: What exactly do you want here? How long are you going to stay? When are you leaving? – and not only from the mouths of officials”.

People without citizenship and language

Stories about emigrants seeking IDs resemble Kafkaesque novels. Exiles faced bureaucratic apparatuses that were totally unwilling to sympathize with them. A man without citizenship was mistrusted. In addition, Germanophobia was growing in the world. Some people even chide the emigrants for leaving the country. Klaus Mann recounted that he was once told:

“A decent citizen has no reason to flee his country, no matter what government is in power.”

The poet Max Hermann-Neisse similarly observed:

“Opposition is not loved anywhere.”

The German legal code provided for deprivation of citizenship only in very limited cases. However, Hitler's regime gave itself the right to deprive of citizenship anyone who did not show loyalty or refused to return to Germany as ordered. At first, the emigrants accepted the loss of citizenship with little fear and even with a touch of irony or bravado. They said that the Reich, by depriving them of their citizenship, had honored them. Alfred Falk, a member of the Human Rights League and the German Peace Movement, even printed on his business card that he was apatride, that is, a stateless person. However, the emigrants quickly realized that Germany had not done them any favors.

The emigrants said that the Reich, by depriving them of their citizenship, honored them

In addition to the fact that the Reich confiscated all of their property, in some countries, such as Switzerland, the loss of German citizenship rendered any existing residence permit invalid, even if the emigrant's passport was still valid. The bureaucrats could deny residence permits due to lack of IDs. Most European countries were not going to grant new citizenship to refugees. The latter could only be legally obtained if the emigrant stayed in the country for three to ten years (as was the case in France and Belgium) and had adequate means to survive. These conditions were supplemented with new points - knowledge of language or culture, military service.

Obtaining temporary refugee status did not provide guarantees either. Without a visa, an emigrant could not travel. For those who did not have a valid passport, obtaining a visa remained impossible, and the diversity of legal norms in Europe made the hunt for a visa a farce. Stefan Zweig described this situation in “The World of Yesterday”:

“Besides that, every foreign visa on this travel paper had thenceforth to be specially pleaded for, because all countries were suspicious of the sort of people of which I had suddenly become one, of the outlaws, of the men without a country, whom one could not at a pinch pack off and deport to their own State.”

The fate of the exiles in Marseille and their struggle for visas, often humiliating, formed the basis of the novel Transit by the novelist Anne Seghers, published in 1944.

The emigrants were forbidden to work (permits were granted in rare cases) and even more so to be politically active. For many of them, their departure was not just a stressful experience, but a virtual repudiation of their past lives. The exiles (especially if they did not speak any language other than German) realized that they would never again be able to publish or work. The writer and physician Alfred Döblin wrote to the Swiss journalist Ferdinand Lyon on April 28, 1933: “I can neither be a doctor abroad, nor can I write. What for? For whom?”

Alfred Kerr, Berlin's most famous theater critic, noted in his “Sentimental Journey,” published on July 1, 1933, in the French magazine Les Nouvelles littéraires:

“No one leaves their homeland for fun. We all love the countryside where we used to be kids. We are attached to the places where we paid tax, and then, it is very hard to speak a foreign language”.

In Prague, Vienna, Zurich and Paris, Kerr continued to go to the theatres, but with a wistful feeling that he was now just a spectator. Kerr could not imagine he might never again be able to write in German. Even someone as privileged as Thomas Mann said:

“I am too good a German, too closely tied to the cultural traditions and language of my country to think about years of exile.”

Financially, the emigrants also lived differently. Heinrich Mann lived in a state of near poverty, just a few kilometers from Lyon Feuchtwanger, who dictated his books surrounded by antique furniture. More often than not, the former citizens of the Reich had no money. They remained outcasts to the new society. The writer Hermann Kesten remarked:

“I do not know to what extent those who have never been forced to leave their country can imagine a life in exile, a life without money, without family, without friends and neighbors, without a native language, without a valid passport, often without an identity card or work permit, without a country ready to accept exiles. Who can understand this situation: to be disenfranchised, rejected by their own country, which persecutes them, slanders them and sends assassins across its borders to kill them?”

Nevertheless, those emigrants, who had the opportunity, wrote books, magazine articles, appeared on the radio and tried their best to make Europe aware of the dictator who had taken over their country. They acted as a warning to a Europe that preferred to remain silent. In the early years of the Third Reich, emigrant propaganda was the only source of reliable information to the world about the extent of Nazi terror.

Emigrant leader

Thomas Mann, in a radio broadcast intended for German listeners on June 26, 1943, said that of all the bloody acts committed by the Nazis, the burning of books on May 10, 1933, had the greatest impact on the world and on the decision of many to emigrate:

“Hitler's regime is a book-burning regime, and so it will remain.”

He added that while the incident had long been a forgotten memory in Germany, it continued to haunt German emigrants abroad. On May 10, 1943, the New York Public Library and 300 other major American libraries lowered their flags to commemorate the book-burning.

Heinrich Mann often recalled being sent a charred copy of one of his novels. Stefan Zweig recounted in his autobiography that one of his friends gave him a book that a student had pierced with a nail. Ernst Toller accompanied the appeal which opened his work “I was a German” “Where were you, my German comrades?” with a note: “Written on the day my books were burned in Germany”. The action, which at first was perceived as frivolous, even farcical, quickly came to be seen as a prologue to great changes in the homeland.

Book burning campaign v-pravda.ru

Thomas Mann, unlike his brother, had long been balancing between the status of a German writer, whose books were still published in the Reich, and the status of an emigrant, which he sized up with extreme caution. The final and public break between Mann and Hitler's Germany provoked an article by the Swiss critic Eduard Korrodi, published on January 25, 1936 in Neue Zürcher Zeitung under the title “German literature in the mirror of an emigrant.” Korrodi condemned an article by Leopold Schwarzschild that had appeared in the French Neue Tage-Buch on January 11. It argued that of all the cultural and material assets of Germany, only one had been fully saved - German literature, which was now entirely out of the country. Korrodi countered Schwarzschild that Thomas Mann's books were still being sold in Germany and reminded him that Mann refrained from identifying himself as an emigrant.

On 3 February 1936, Thomas Mann sent a letter to the newspaper. Although he refused to criticize writers who had not emigrated, he also reproached Korrodi for conflating “Jewish literature” with the entire antifascist emigration, reminding him that many of the writers who had left were not Jewish (such as himself and his brother Heinrich). Mann ended his letter with a few lines from August von Platen that left no doubt that he too would now consider himself an émigré:

“This conviction, nourished every day by thousands of humane, moral and aesthetic observations and impressions, that nothing good can be expected from the present German regime, either for Germany or for the world, has made me leave a country whose spiritual traditions have deeper roots in me than in those who for three years now have been hesitant to deny me the title of German in front of the whole world. And I am deeply convinced that I did the right thing by my contemporaries and my descendants by joining with those to whom the words of the truly noble German poet August Platen can be applied: “But those who are filled with an aversion to evil, / It could also drive them abroad, / If evil is revered at home / The wiser course is to leave one's native land, so as not to merge with an unwise generation, not to know the yoke of blind plebeian malice.”

Yours faithfully,

Thomas Mann.”

The Nazis reacted immediately, stripping the writer of his German citizenship. Mann's radical break with Germany obviously upset Hermann Hesse, who sought to maintain the same ties with his homeland. Mann wrote to Hesse on February 9, 1936:

“Dear friend Hesse, don't grieve over the step taken <...>. To many sufferers I have done a good deed, as shown by the flow of letters <...>. I have never looked at what I did as a break with you <...>. I will continue my work and let time confirm my prediction (made rather late) that nothing good will come out of National Socialism. But my conscience would have been impure in the face of time if I had not predicted this.”

Since then, Thomas Mann, formerly apolitical, effectively became the leader of the emigration. He spoke on its behalf, defended the fleeing Germans and at every opportunity reminded them of another Germany that continues to live, albeit no longer within the territorial boundaries of the former country, but where people write and think in German, where honor and freedom are still defended. In 1939, Thomas Mann wrote about the Germans of the Third Reich in his book “Lotte in Weimar”:

“They don't love me, so be it. I don't love them either, and we're even. They think they are Germany, but I am. Let everything else die, roots and shoots, but it will survive and live on in me.”

The place of a different Germany in the world

During the Second World War, society knew no Germanophobia as pronounced as during the First World War. Public opinion was also influenced by the activities of German immigrants. In Britain, for example, the question “Who is the main enemy - the people of Germany or the Nazi government?” in 1939 was answered “the people” only by 6%. In 1940, after an anti-German press campaign, this percentage rose to 50, but then dropped again. British propaganda, just like Soviet or American propaganda, tried to maintain a distinction between “Nazis” and “Germans.” According to Mass Observation statistics, during World War II, 54% of the British population expressed sympathy for the German people and declared that the war was “not their fault” and that it was “Hitler's war, not the German people's.” The same rhetoric was supported in the USSR. Joseph Stalin wrote:

“It would be ridiculous to identify the Hitler clique with the German people, with the German state. The experience of history tells us that Hitlers come and go, but the German people, and the German state, remain.”

However, it would be a mistake to say that the Germans were welcomed with absolute joy.

Erich Maria Remarque's novel Shadows in Paradise is about refugees who came to the United States at the end of World War II:

“You are not an American? - asked the girl.

“No, German.”

“I hate Germans.”

“Me too,” I agreed.

She looked at me in amazement.

“I'm not talking about those present.”

“Me, too.”

“I'm French. You must understand me. The war...”

“I understand,” I said indifferently. It was not the first time I was being made responsible for the crimes of the Nazi regime in Germany. And gradually it stopped touching me. I spent time in an internment camp in France, but I did not hate the French. Explaining this, however, was useless. Anyone who can only hate or only love is enviably primitive.”

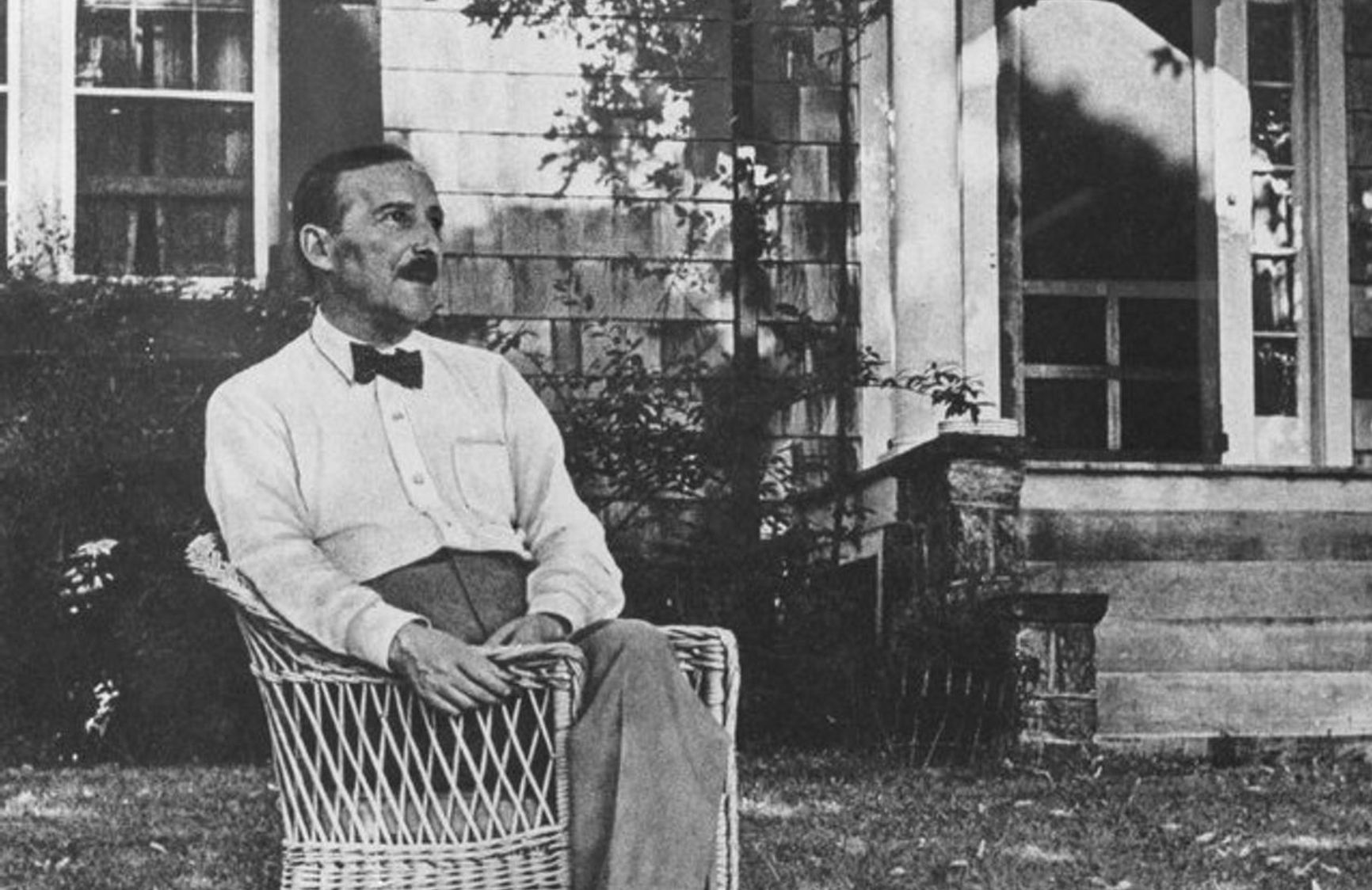

The emigrants were interned in special camps, interrogated, arrested, they were monitored, their every activity was suppressed. They were much criticized for the very fact of their departure from the homeland - they were reproached for betraying the country and returning to it wearing foreign army uniforms. Even when it was long over, during the 1961 election campaign, Willy Brandt, the future German chancellor, was constantly asked, “What were you doing twelve years while abroad?” Inside Germany, it seemed to many that the exiles had been happily living in peaceful cities while Hannover, Dresden, and Berlin had been bombed. And even though those reproaches were in part justified, behind them were stories of difficult fates, difficult decisions and dramatic outcomes: the writers Ernst Toller, Stefan Zweig and Walter Hasenclever committed suicide, unable to bear the weight of emigration.

Stefan Zweig in Brazil in 1942 snob.ru

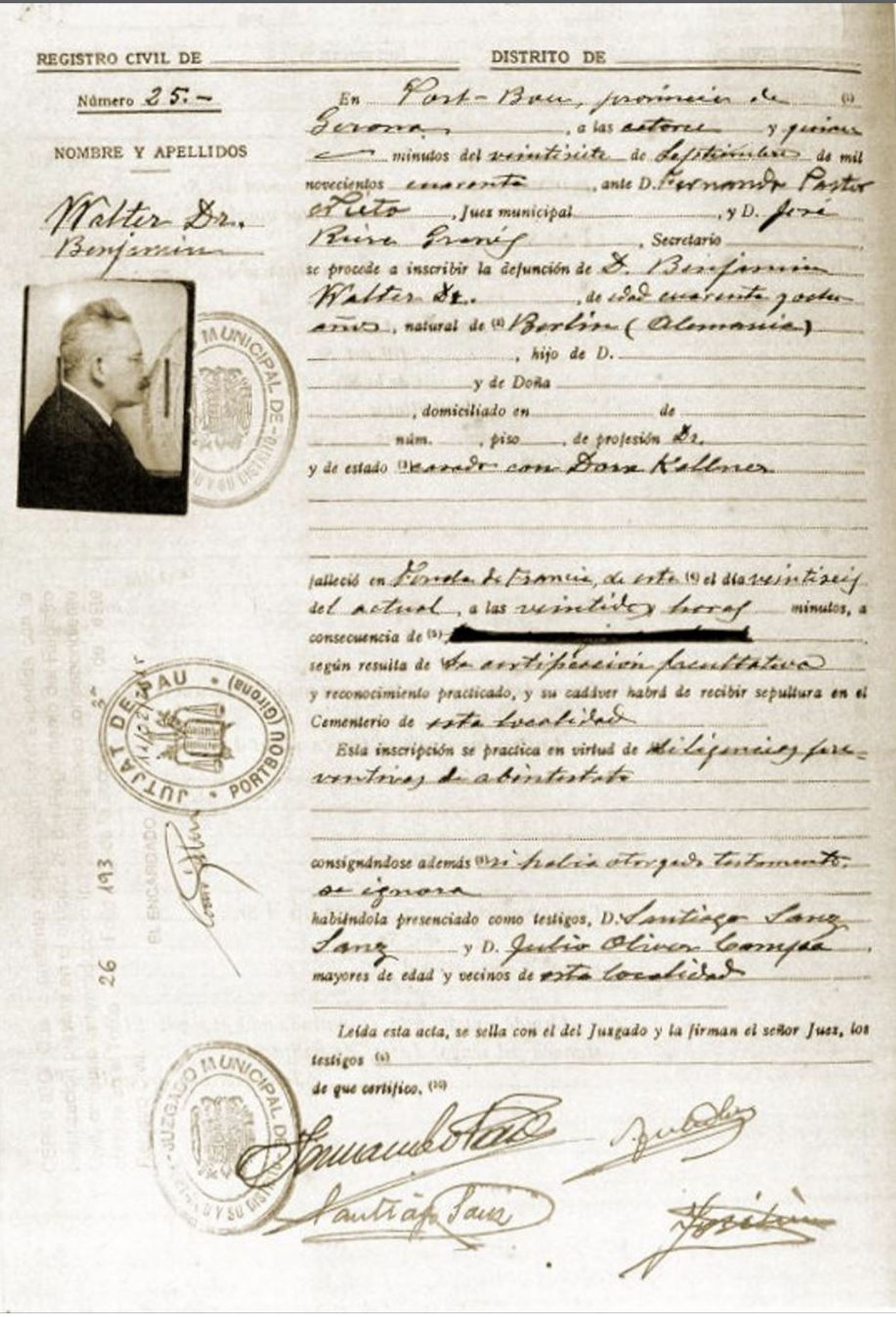

The philosopher Walter Benjamin committed suicide in the Spanish border town of Portbou: despite having an American visa, the Spanish threatened to deport the entire group of emigrants to occupied France.

Walter Benjamin's death certificate urokiistorii.ru

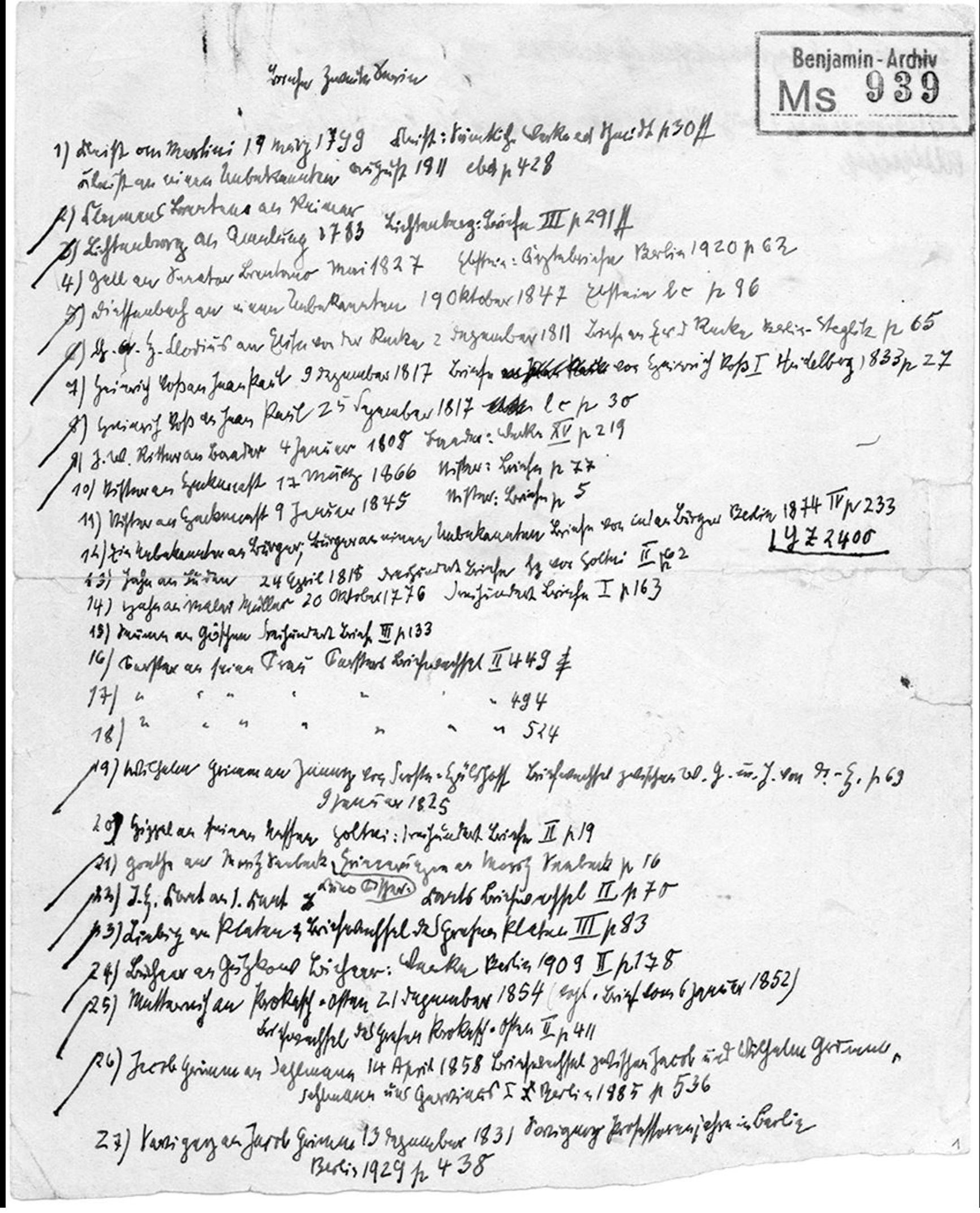

The emigrants' intellectual struggle with the Third Reich did not lead to significant consequences. Discussing Deutsche Menschen (a book by Walter Benjamin for which he collected in the archives, and commented on, the letters of German intellectuals over a hundred years to show what German humanism could be; the title and publication under a pseudonym were to facilitate the sale of the book in Germany; in Russia the book was more commonly translated as “The German People”) intended for distribution in the Reich, Theodor Adorno observed: “This book reached Germany unharmed and has had no political impact there.”

Benjamin's manuscript. List of 31 letters, 13 of which were published in Frankfurt Zeitung between April 1931 and May 1932 grundrisse.ru

Despite the calls by the antifascists, the European states never took a stand against Hitler until the conflict escalated to the stage of a world war. Klaus Mann warned everyone in “The Turning Point”:

“You are in danger. Hitler is dangerous. Hitler means war. Do not believe in his love assumed by the world! He lies. Do not make a deal with him; he will not keep his promises. Do not be frightened of him. He is not as strong as he seems, not yet! Don't let him become so. In the meantime, a gesture, a strong word on your part, is enough to prevent him from doing so. In a few years the price will be higher, it will cost you thousands of human lives. Why wait? Break off diplomatic relations with him! Boycott him! Isolate him!”

The émigré antifascist movement did not do too well. Yet the very nature of its struggle was heroic. It is naive to believe that tens of thousands of emigrants could change the course of history simply because of their intelligence and attachment to Germany. They lost the battle with Hitler, but they won a far more important one: the right to represent a different Germany. The emigrants invariably reminded the world that the Third Reich was not Germany and Hitler was not the German people. In April 1945, when the concentration camps were discovered, Alfred Kantorowicz noted that it took a world war with millions of deaths for the world to learn what the emigrants had been constantly repeating since 1933.

In 1945 at the Library of Congress, Thomas Mann read a report entitled “Germany and the Germans,” which called for Germany not to be divided into good and evil:

“Any attempt to arouse sympathy to defend and to excuse Germany, would certainly be an inappropriate undertaking for one of German birth today. To play the part of the judge, to curse and damn his own people in compliant agreement with the incalculable hatred that they have kindled, to commend himself smugly as ‘the good Germany’ in contrast with the wicked, guilty Germany over there with which he has nothing at all in common, – that too would hardly befit one of German origin. For anyone who was born a German does have something in common with German destiny and Germany guilt. <...> German misfortune is only the paradigm of the tragedy of human life. And the grace that Germany so sorely needs, my friends, all of us need it.”