“Pogrom” is one of the few words that European languages borrowed from Russian. Back at home, it seemed to have fallen out of use in recent decades, becoming a relict of the past – until the Makhachkala airport riot gave it a new relevance. That said, Judeophobia was a permanent trait of the Russian Empire, and the history of Jewish pogroms counts many brutal chapters. The authorities almost invariably failed to act, and in some cases even encouraged the looting and the slaughter.

Content

Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Elizabeth of Russia

The wave of pogroms under Alexander III

The Kishinev pogrom of 1903

The wave of pogroms of 1905: Odessa

The triumph of injustice

Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Elizabeth of Russia

As early as in the 16th century, Ivan the Terrible refused to let Jewish merchants into Moscow, saying the Jews were “culpable of wrongdoing, turning our people off Christian faith, and bringing poisonous potions into our land.” Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich expelled Jews from the cities that fell under his rule: “And the Jews shall not be and shall have no residence in Mogilev ... Send the Jews from Vilna to live outside the city.”

Peter the Great was relatively lenient to the Jews (in 1708, he even personally stopped a pogrom his soldiers started in Mstislavl and ordered to hang 13 of the pogromists), but once his widow acceded to the throne, the Supreme Privy Council issued a decree banishing Jews from the country: “Jews, both male and female ...shall all be expelled out of Russia abroad immediately and henceforth shall not be allowed to return under any circumstances, and all authorities shall be warned accordingly.” Peter the Great's daughter, Elizabeth of Russia adhered to a similar position.

However, up to the latter half of the 18th century, anti-Semitism was not a major issue in Russia for a simple reason: Jews were few and far between. Things changed after the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, when a huge number of Polish Jews suddenly found themselves under Russian jurisdiction. Already subjects of the empire, they could no longer be simply “prevented” from entering it. The government had to come up with something new, so they invented the Pale of Settlement: an area outside of which Jews (except for those who converted to Christianity and some other categories that varied over time) were forbidden to live and work. The Pale of Settlement was in place from 1791 to 1917, although its borders changed, often along with the state borders of the empire.

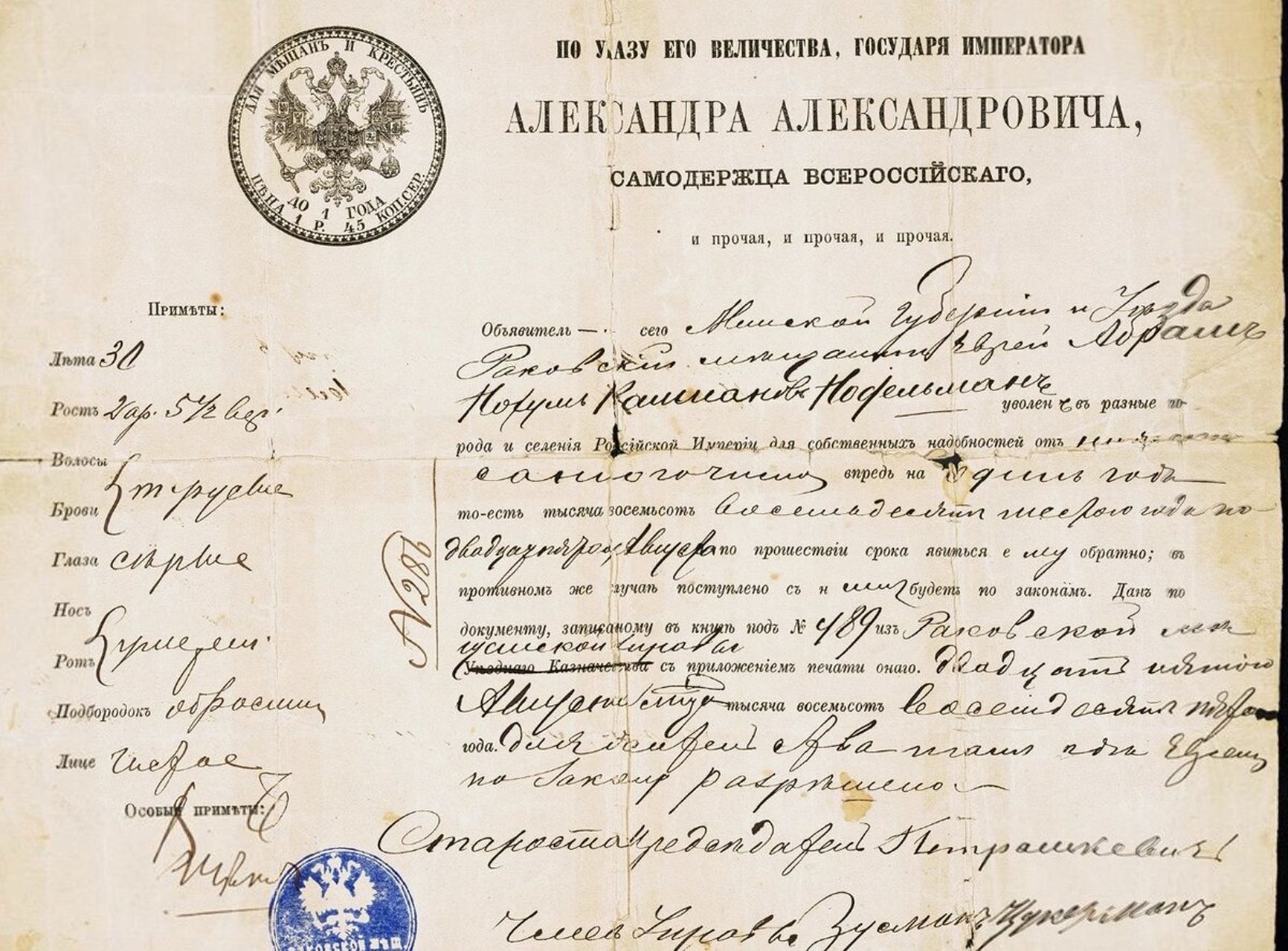

Temporary pass for a Jew to travel beyond the Pale of Settlement to other parts of Russia on family matters. Late 19th century

By 1825, the Russian Empire had found itself in a completely new situation: as demographer Pavel Polyan writes, with 1.6 million Jews, Russia was home to nearly half of world Jewry.

As of 1825, 1.6 million Jews lived in the Russian Empire – nearly half of the world's Jewry

Around the same time, in 1821, the empire saw its first major Jewish pogrom – in Odessa (the name of Odesa in imperial Russia). The pogrom was initiated by members of the Greek diaspora, which controlled the bread trade in the region and detested the increasing role of Jewish merchants. As a pretext, they used the murder of Greek Patriarch Gregory, who’d been brutally assassinated in Constantinople by the Turks, but Odessa’s Greeks were spreading rumors that “the Jews were to blame.” The patriarch’s body was brought to Odessa, and on the day of his funeral, Jewish pogroms broke out in three parts of the city – but the non-Jewish population hardly supported them at the time. The instigators of the pogroms were never found.

In 1859, Odessa saw another major pogrom, once again organized and led by the Greeks. The local authorities sent police to quell the pogrom but were reluctant to antagonize the influential Greek diaspora and tried to treat the incident as a trivial brawl.

The next Odessa pogrom, in 1871, lasted three days and damaged 863 houses and 552 shops. This one was different from the previous ones: although the Greeks started it too, this time other ethnicities joined the unrest. The reaction of the authorities, who turned a blind eye to the pogrom for three days and reacted only on the fourth, is also noteworthy. “Gloating, the local government and the general public reveled in the destruction and encouraged the aggressors to loot,” wrote historian Yuliy Gessen.

And yet that was only the backstory. The pogroms in Russia reached full force in 1881.

The wave of pogroms under Alexander III

Almost all of the Romanovs were anti-Semites to a degree: even “enlightened” Alexander II, who somewhat liberalized the position of the Jews, could easily be heard saying things like “the people are generally courteous but extremely unkempt and resemble Jews” (his take on Italians). Meanwhile, his successor, Alexander III, made no secret of his anti-Semitiс views. A man of less than stellar education, he sincerely believed in blood libel and was Judeophobic even in everyday life. Count Sergei Witte, Russia's first Prime Minister, recounted how the Emperor refused to give loans to Jewish bankers because he “couldn't fathom why to offer any kind of loans to Jews” and sometimes rejected cooperation with Jews even to the detriment of his own interests.

Alexander III was a Judeophobe even in everyday life

This had an immediate impact on policies: not only did Alexander III repeal all the relaxations introduced by his father, but he also tightened anti-Jewish laws whenever he could. “Temporary rules”, which prohibited Jews from settling in the countryside, purchasing real estate, renting land outside of towns and shtetls, and doing business on Sundays, both deprived many Jewish families of their livelihood and, as publicist Semyon Dubnov notes, ushered in legitimate pogroms. And they were only a fraction of the anti-Jewish laws passed under Alexander III, as the policy of the “peacemaking tsar” was blatantly anti-Semitic. His attitude could not but affect public sentiment. Admittedly, the government was unlikely to initiate the pogroms, but it spared no effort in showing that pogroms were allowed.

The impression that the government tacitly approved of pogroms, if not directly called for them, was a major factor behind the wave of pogroms in 1881-1884, which was formally triggered by the assassination of Alexander II. Soon after the attack, many newspapers were quick to place blame on the Jews, directly or indirectly.

The accusations were absurd: only one of the arrested Narodnaya Volya terrorists, Gesya Gelfman, and she was far from being the mastermind. This did nothing to assuage the anti-Semitic press; many were especially outraged that Gelfman, who was pregnant, had had her execution postponed until after childbirth. Some newspapers explicitly announced upcoming anti-Jewish marches on Easter Eve. Given the level of censorship in the time of Alexander III, such outbursts couldn’t have been printed without the tacit approval of censors, who were the mouthpiece for the state authorities. And that was exactly how the general public interpreted the situation: what’s printed has to have been approved.

The wave of pogroms began on April 15 in Elisavetgrad (now Kropyvnytskyi) with a petty clash between a tavern keeper and a visitor over a broken glass. A brawl that began in the tavern soon spilled over into the street. “Booing and shouting, the crowd rushed in pursuit of the fleeing Jews, smashing windows in Jewish shops along the way... Ravaging shops, throwing personal effects and goods outside, and destroying any Jewish property they could lay their hands on,” eyewitnesses recalled.

The patrols tried to intervene, but showed little enthusiasm: firstly, there were no orders from above, and secondly, because of “the crowd of onlookers from among the educated and the wealthy: ladies, women with infants and young children, against whom the officers did not dare to use force.” The next day the pogroms resumed with a new vigor: shops smashed, Jews beaten, the police and cadets trying – and failing – to stop the rioters. It wasn't until regular troops entered the city that the pogroms in Elisavetgrad were curbed. But it was too late as the unrest was rapidly engulfing the neighboring towns. In total, the wave of pogroms rolled over 150 settlements.

All of these pogroms had a common trait: the participants were absolutely convinced of their impunity. A rumor persisted that there was even a royal decree to beat the Jews, a decree that was never made public because the Jews allegedly interfered with it. Besides, the pogroms were not entirely spontaneous: provocateurs appeared the day before in almost every settlement where they broke out.

They argued that “Jews are being beaten everywhere, and this goes unpunished,” that «the Emperor dislikes Jews» and won't give soldiers the order to “shoot at Russian people,” that they “personally heard a police officer cite the Emperor’s decree allowing the beating of the Jews since they are oppressing the Russian people,” or that “the Emperor is traveling abroad and ordered for all Jews to be beaten before his return.” Leaflets by anonymous authors were posted everywhere, calling for the “eradication of the heinous Jewish tribe” and conveniently announcing the dates of upcoming pogroms.

Leaflets called for the “eradication of the heinous Jewish tribe” and conveniently announced the dates of upcoming pogroms

There are different opinions about the extent to which the pogroms were planned. A note submitted to the government by Baron Ginzburg stated that most of the pogroms had occurred in settlements along the railroad, and all of them had followed the same scenario: first, a rumor emerged about an upcoming pogrom on a particular date; on that day a “gang of ragamuffins” arrived by train, got drunk, and started the pogrom, taking the cue from their ringleaders (who had lists with addresses of Jewish apartments and shops in advance). In the crowd, there were always a few instigators, reading out anti-Semitic articles and presenting them as decrees authorizing the beating of Jews.

The note also stated that the authorities tacitly sympathized with the pogromists: despite knowing the dates of the pogroms in advance, they never took preventive measures. The authorities sometimes confirmed this. Thus, General Novitsky, an eyewitness of the Kiev (currently Kyiv) pogrom of 1881, wrote that the Jews “undoubtedly owed this pogrom to the governor-general of Kiev, Adjutant General Alexander Drenteln, who hated Jews with all his heart and gave carte blanche to rampant mobs of ruffians and Dnieper tramps who openly thrashed Jewish properties, shops, stores, and markets, even in the presence of the general himself and his troops, who’d been summoned to curb the unrest. The troops became impassive spectators of all the lawlessness, havoc, and robberies of Jewish properties, and their morale was so low that they even looted Jewish stalls on outdoor markets, which I saw for myself.”

The Pogroms of the 1880s

Print by Johann Schonberg

The same failure to act, bordering on complicity, characterized the Balta pogrom in March 1882. This pogrom turned out to be one of the most violent, with 211 people injured, 12 killed, at least 20 cases of rape reported, and 976 houses and 278 shops looted.

“Deliberately or inadvertently, [the authorities'] actions only fueled the riots,” writes historian Arkady Zeltser. “Thus, on the first day of the pogrom, the troops prevented Jews from passing over the bridge to the Turkish side, which enabled the rioters to destroy Jewish property there; further on, the authorities released 24 Christians arrested on the first day of the pogrom under the pressure of the mob, while the detained Jews remained under arrest until the governor’s arrival. ... The troops tried to contain the riots to some extent; patrolling the town, the local battalion cordoned off the crowd and held it for almost an hour ... but when the police officer, the military chief, and the police inspector appeared, the chain was broken, and the mob, accompanied by peasants who had arrived from the villages, pounced on the liquor store, got drunk and began to smash and crush everything in their path. ... The police officer disappeared somewhere, and no one saw him throughout the pogrom. The police and soldiers aided and abetted the hooligans. Military chief Karpukhin patrolled the city throughout the day, accompanied by soldiers, who, however, did not counter the pogrom.”

During the subsequent debriefing, Balta’s authorities tried to convince their superiors that the riots had been organized... By none other than the Jews themselves.

Other government representatives blamed the Jews for the pogroms too, although indirectly, by saying they’d pushed people to the extreme. The most common explanations include the ‘economic domination’ of Jews, their making drunkards of Russian people, and their ‘malicious’ commercial activities. Jewish communities were even reproached for their secluded, tightly-knit nature – which they largely owed to the Pale of Settlement and other anti-Semitic laws.

The wave of pogroms abated in 1884, after causing the first major outflux of Jews from the Russian Empire. The First Aliyah, which included about 2 million Jews, was largely triggered precisely by the pogroms.

The Kishinev pogrom of 1903

Under Nicholas II, pogroms resumed. In the 1890s, they flared up sporadically all over the country. But the most outrageous bloodshed occurred already in the 20th century in Kishinev (now Chisinau), on April 6 and 7, 1903.

This pogrom was all the more shocking because Bessarabia was considered an oasis of calm. Unfortunately, the government had created an atmosphere that strongly favored pogroms.

Firstly, the post of Minister of the Interior and Chief of the Gendarmes during these years was occupied by Vyacheslav von Plehve, an open anti-Semite. Many eyewitnesses named him as one of the main culprits and organizers of the Kishinev pogrom (Count Witte also shared this opinion). And while today's historians doubt his immediate involvement, hardly anyone questions his approval of pogroms. General Kuropatkin, former Minister of War under Nicholas II, looks back on a conversation with Plehve in his diary: “As well as from the Sovereign, I heard from him that the Jews should be taught a lesson, that they’d grown arrogant and were spearheading the revolutionary movement.”

The important caveat is “as well as from the Sovereign.” Nicholas II was as much of an anti-Semite as his father – and even surpassed him. He appears to have sincerely believed in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, openly sympathized with the nationalistic Union of the Russian People, which thrived under his rule, and was quick to grant pardon to arrested pogromists. All of the above instilled confidence that pogroms were not just acceptable but desirable to the authorities.

Nicholas II sincerely believed in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and openly sympathized with nationalists

The groundwork for the Kishinev pogrom was laid by Bessarabets, a newspaper published by the infamous Black Hundred activist Pavel Krushevan, who had also been the first to release The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in 1903. The newspaper painted the previous day's murder of 14-year-old Mikhail Rybachenko (as the investigation soon found out, he'd been killed by a relative over an inheritance) as a brutal ritual killing. Day after day, journalists reveled in the gory details (the killers had allegedly sewn the boy's eyes, ears, and mouth shut) and explained that the Jews had released the child's blood and used it to make matzah. In addition, the Jews were blamed for all their other purported “transgressions.”

The date of the forthcoming pogrom was no secret, with public places strewn with anti-Semitic leaflets, and rumors spreading throughout the city that the tsar had issued a decree “to beat the Jews within three days after Easter.” The Jewish community reached out to the local government with a request for protection, and the Christian population preemptively painted crosses on their doors and put icons in the windows.

The pogrom began on April 6 (19 N.S.), the first day of Orthodox Easter. At first, the pogromists threw stones at the windows of Jewish homes, then started smashing shops. There were no human casualties early on, but the authorities’ indifference convinced the aggressors of their absolute impunity. Dr. Moses Slutsky, the chief physician of the Jewish hospital, who treated the pogrom victims, recalled that more wounded and killed were arriving every minute: “A cabman I knew and whose services I often used brought a severely wounded man to the hospital and left; half an hour later, his own corpse was brought in his carriage.”

“The faces of the dead were disfigured to such an extent,” writes the doctor, “that even the closest relatives of the deceased – their wives and children – could barely recognize them: broken skulls, from which the brains fell out, smashed faces, covered with blood and down... Often, the dead could only be identified by what they were wearing.” There was no fleeing from the pogromists: they broke into houses, beat up anyone who got in their way, searched for those who’d hid, and chased everyone who tried to escape.

Kishinev, after the pogrom

As Slutsky recalls, a family climbed to the roof, and “the thugs followed them. Soon the thugs caught them and started pushing the poor things off the roof one by one as the crowd below roared with laughter.” Almost all of the victims died. Another family hid in a shed but also unsuccessfully: a neighbor stabbed the head of the family with a knife, and then “the thugs beat him to death with clubs in front of his wife and children.” Many of the pogromists had indeed been their victims’ good neighbors if not friends. “Interestingly, there was a town policeman on duty near the house and a few soldiers not far away,” remarks Slutsky, “And yet, despite desperate pleas for protection, they remained passive onlookers, excusing themselves by saying they’d received no orders to intervene.” By contrast, according to the doctor's testimony, the police sometimes detained Jews who tried to set up self-defense units.

It wasn’t until the evening of the second day that the local garrison was authorized to use arms against the pogromists. The soldiers were given ammunition – but never fired even a single shot. “Within an hour and a half, peace was restored throughout the city. There was no need for bloodshed or gunfire. All it took was certainty,” wrote Vladimir Korolenko in his essay on the Kishinev pogrom.

Finally, arrests were made, and the casualties were tallied: 49 killed, 600 wounded, and 1,500 houses destroyed – more than one-third of all Kishinev households. “Everywhere, the trees were sprinkled with down like snow. Holes from ripped-out doors and windows gaped. The streets were strewn with fragments of furniture, smashed crockery, torn bedding, clothes, and pages from Jewish books. ... Ransacked synagogues, where Torah scrolls had been torn and desecrated,” recalls Slutsky, looking back on the city after the pogrom.

The wave of pogroms of 1905: Odessa

In 1905, the pogroms broke out with renewed vigor, and the authorities appeared to have become even more forgiving – for a host of reasons. First, they viewed Jews as potential “insurgents” (the propaganda of the time spared no effort in trying to equate “Jew” with “revolutionary,” making this, in a sense, a self-fulfilling prophecy). Secondly, Nicholas II saw the Black Hundreds as the core of his support in the troubled days, willingly endorsing their activities. Finally, the government was only too willing to direct the rage of the poor toward the Jews, distracting them from the actual source of their troubles.

The pogroms followed the same pattern, always starting with instigators spreading rumors of a Jew desecrating an icon, for instance, or shooting at the Emperor’s portrait. Police and troops often remained passive. However, Jewish self-defense groups had by then emerged in many towns and cities and sometimes managed to stop pogromists, who were unaccustomed to any resistance. They were especially efficient if the authorities did not interfere with their defense (which was not always the case).

The wake of the Odessa pogrom

The pogroms peaked in October 1905: 690 episodes in 102 settlements, with a total death toll ranging from 800 to 4,000 (by different estimates). The bloodiest one occurred in Odessa (currently Odesa) on October 18-21, 1905.

When the pogrom began, the situation in the city was already unstable, so all it took was a tiny spark. A conflict occurred between two protests; a child died, and the mob was quick to blame the Jews. On the first day, Jewish self-defense units were quite successful in containing the riots, disarming and detaining at least 200 pogromists. Unfortunately, the local authorities intervened, stepping up for the opposite side. The town mayor Dmitry Neidgardt ordered to remove police officers from the streets (allegedly fearing for their safety), and the governor-general A. Kaulbars, according to some sources, ordered the troops to use all kinds of weapons to suppress Jewish self-defense. The pogromists were given the green light.

After that, the pogroms continued for another four days, and many soldiers also joined in, according to eyewitness accounts. A Russkoye Slovo correspondent telegraphed from Odessa: “The riots are taking on grand, threatening proportions, accompanied by killings, violence, rape, attacks on civilians, and endless looting. Huge crowds of hooligans, reinforced by residents of the suburbs, scum, port beggars, armed with crowbars, clubs, and stakes with iron ends, are moving along the streets in groups, destroying and looting everything in their path.”

The riots spilled over into the suburbs. Jews who tried to escape were drowned at sea or killed right on the trains. The police did not interfere; from the onset, rumors circulated among the pogromists about orders to leave them alone until October 21. And indeed, the order to use force was issued only on the morning of October 22, and the riots immediately stopped.

According to various estimates, the Odessa pogrom killed from 500 to 1100 people. There was not enough space in the cemetery, and Jews had to be buried in mass graves. Another 3,000 people were wounded. Tens of thousands were left homeless.

The triumph of injustice

The pogroms were followed by trials, but more often than not they became a new source of abuse for the victims: “procedural pogroms,” as lawyers put it. Jews were treated like criminals. The sworn attorney and publicist Lev Kupernik wrote about the “presumption of a Jew's guilt”: “Every man is considered decent until the contrary is proved; conversely, every Jew is considered a scoundrel until the contrary is proved.”

The trial after the Gomel pogrom in 1903 is very indicative in this sense. Thirty-six Jews from self-defense groups ended up in the dock with the pogromists. Eyewitnesses recall that the court was biased against both the Jews and their defenders: at one point, the atmosphere became so outrageous that the Jews’ defenders resigned halfway through the session. Eventually, 23 of the 36 Jews were convicted, with the same punishment as the pogromists. The indictment was a clear message from the authorities: Jews weren't allowed to defend themselves against pogroms.

The indictment was a clear message from the authorities: Jews weren't allowed to defend themselves against pogroms

The fate of the Odessa mayor Dmitry Neidgard, who was guilty of at least failure to act during the pogroms of 1905, is also noteworthy. Under public pressure, he was removed from office but received subsequent promotion, becoming a senator, then a Privy Councillor, and in 1907, the Odessa Duma awarded him the title of honorary citizen of Odessa.

Nicholas II himself made no secret of his allegiance. “The people were outraged by the insolence and impudence of revolutionaries and socialists, and since nine-tenths of them are Jews, all the anger fell on them – hence the Jewish pogroms,» he wrote to his mother on October 27, 1905.

The global community sharply condemned the pogroms in the Russian Empire. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt demanded that Nicholas II amend the anti-Semitic laws (primarily on settlement), but the emperor refused, even though it meant losing much-needed foreign loans. He was not in a hurry to offer pogrom victims financial aid either, believing they were already receiving enough from domestic and Western Jewish organizations.

The Kishinev pogrom and subsequent incidents are believed to have indirectly influenced even the outcome of the Russo-Japanese War because American bankers of Jewish descent financially supported the Japanese in protest against Russia's policy toward the Jews. In the future, the anti-Semitism of Nicholas II and his entourage served them poorly, pushing Jewish youth, who had no chance for a normal life under their rule, to join the revolutionary movement.