Now that the institution of the bar has been destroyed in Belarus and is hanging by a thread in Russia, the two states are about to complete their transformation into dictatorships. In this sense, they are gearing back toward the USSR, where the defense was an accessory to the punitive justice system and did the bidding of the state – especially under Stalin. And yet, even at the height of Stalin's cannibalistic terror, Soviet defense attorneys sometimes managed to meet their definition in spite of (and sometimes, paradoxically, thanks to) the system. History holds multiple examples of successful cases from their legal practice.

Content

Defense attorneys as opinion leaders in modern history

The Bolsheviks' theory of law and dislike of lawyers

How the old judicial system was dismantled and how lawyers contributed to the process

Early days of the Civil War and Red Terror: Crimes against the revolution

The NEP and the revival of the bar

The birth of Stalinism and purges in defense boards

Legal nihilists vs. champions of legitimacy

The Communist Party and the bar: Attempted control

The terror and the bar

The Astashin case: A Great Terror trial

The war and the bar

The Artemenko case: A wartime trial

Implications of the regime's pressure on the legal system

Defense attorneys as opinion leaders in modern history

In post-feudal societies, legal practice was necessitated by the need to resolve property disputes and therefore enjoyed support from the authorities and elites. However, that doesn't mean lawyers always supported the regime. Aside from aspiring politicians, a career in law was often chosen by individuals concerned about societal disenfranchisement and inequality. Former lawyers Georges Danton and Maximilien Robespierre established and led the Republic in France. One of the creators of the Weimar Republic, Hugo Haase, and its third Chancellor Constantin Fehrenbach were also lawyers.

In the Russian Empire, the bar was also a highly influential and rebellious stratum. The share of deputies with a legal background in pre-revolutionary Russian dumas (advisory councils) fluctuated around 5%, despite them accounting for less than 0.01% of the general population. Many lawyers went into politics with the outbreak of the February and October revolutions. Thus, after the February Revolution of 1917, lawyer Alexander Kerensky first assumed the post of Minister of Justice and then headed the Provisional Government. After the October Revolution, also in 2017, the Bolsheviks appointed former lawyers from among themselves as People's Commissars of Justice. The Bolsheviks’ leader Vladimir Lenin had practiced law as well.

The Bolsheviks' theory of law and dislike of lawyers

The attitude of the Bolsheviks, who were the most radical among Russia's revolutionaries, towards the bar was largely negative. Lawyers were thought to be too closely linked with the liberal and parliamentary movements or rival socialist parties. In addition, lawyers had the reputation of being “casuist windbags” who “mislead decent people.” The condemnation of their livelihood also played its part. A defense attorney was seen as the unscrupulous mercenary of any scoundrel who hires him. In the heat of the intra-party struggle, Stalin, in a letter to Molotov, twice called his opponent Bukharin a “lawyer,” using the word as a synonym of “conman,” “swindler,” or “corrupt official.”

Stalin refers to his opponent Bukharin as a “lawyer” – in the sense of “conman” – twice in a letter to Molotov

Another, and in some ways more pertinent, explanation for the adverse attitude toward lawyers in the early Soviet Union is the Bolshevik interpretation of judiciary power. The regime viewed courts only as an instrument of class struggle, not a place for the restoration of abstract justice. Vladimir Lenin's 1918 report stated that the pre-revolutionary court “portrayed itself as defending the public order, while in reality, it was a blind, subtle instrument of ruthless suppression of the exploited, defending the interests of the money bag.”

During a debate on the development of a criminal code, Soviet lawyer Mieczyslaw Kozlowski added in 1921: “The courts are in equal share organs of power and organs of dictatorship. Forget the illusions about the courts’ independence. ... These are the executive bodies of the proletariat.” Professor Mikhail Strogovich's 1938 textbook on criminal procedure draws the line: “The court is a government body that protects the interests of the ruling class.” Thus, the Bolshevik notion of legal justice rests on the idea of progress in the most radical sense. What is progressive, revolutionary, and proletarian is just. Meanwhile, defense attorneys were considered a vestige of the bourgeois past.

A 1938 criminal procedure textbook by Mikhail Strogovich

Moreover, the proponents of this approach were polarized as well. One faction insisted on abolishing all traditional forms of courts (an approach branded as “legal nihilism” by American scholar Eugene Huskey). Representatives of this group believed the only courts the nation needed were revolutionary courts or commissions guided by considerations of a “revolutionary sense of justice” – that is, awareness of the pivotal transformation of society.

This complete rejection of the conventional legal practice was countered by another view, which proposed to use the existing forms of law, adapting them to the current needs. This group, which advocated for upholding written and systematized laws, can be called “champions of legitimacy.” The coexistence of the two approaches explains why the Bolsheviks initially decided to keep the institution of the bar.

How the old judicial system was dismantled and how lawyers contributed to the process

At first, the Soviet judicial experiment developed along the lines of compromise between the two factions: razing the old system to the ground, the Bolsheviks intended to keep some of its elements with only slight modifications. Between November 1917 and July 1918, three court decrees were issued, demolishing the imperial justice system with its institutes of prosecution and investigation. Courts became elective. The bar was replaced by “boards of legal defenders,” which provided legal support by order of the courts. The boards maintained a certain independence from the People's Commissariat of Justice, which was headed by the rather moderate Isaac Steinberg and then Petr Struchka, both former lawyers themselves.

Isaac Steinberg, People's Commissar of Justice of the RSFSR from December 1917 to March 1918, member of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Yiddish writer

The dismantling of the system faced fierce resistance from lawyers. The boards of sworn attorneys (as lawyers were officially referred to before the revolution) refused to dissolve voluntarily. At first, the young government was hesitant to do anything about it. The boards were not forcibly disbanded until August 1918.

Despite their initial boycott of the Soviet government, lawyers soon began to implicate themselves in the cases of the “democratic” Soviet justice in early 1918. Back then, lay assessors were often selected randomly, and some were particularly susceptible to the honed rhetorical skills of the old bar, which resulted in a curious outcome in many cases. Former sworn attorney Sergei Kobyakov wrote in his memoirs:

“Some of the lay assessors were women, often very respectable old ladies, who’d apparently been driven into the Communist Party by hunger. After a few touching phrases uttered by the defense counsel, these old ladies would begin to cry, and the sentences in the district court were extremely lenient, sometimes to the point of absurdity.

Once the court tried a Red Army soldier who’d returned from captivity shortly before that. A policeman at the Sukharev Tower offended his comrade. The comrade ran to the Spassky Barracks and complained about the offense. The defendant ran into the street with a shotgun, sought out the assailant, and shot him dead at point-blank range. When the defendant began to recount his suffering at the front and in German captivity, the assessors wept.

The verdict was as follows: despite having been found guilty in the murder of a policeman, the soldier got away with a 'public reprimand'.”

Early days of the Civil War and Red Terror: Crimes against the revolution

In the summer of 1918, the Bolsheviks cracked down on the “enemies of the revolution.” Their efforts climaxed in the passing of the Decree on Red Terror on September 5. The harsh policy was motivated by the outbreak of the Civil War. As the new government struggled to centralize the nation and establish a dictatorship through mass terror, the remnants of the bar were also affected.

On November 30, 1918, the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets adopted the Decree on the People's Court, thus reforming the People's Commissariat of Justice. Authored by Dmitry Kursky, another former lawyer, the decree provided for the replacement of the “boards of legal defenders” with rather amorphous institutions referred to as “boards of defenders, prosecutors, and representatives of the parties in civil proceedings.” From then on, defendants couldn’t hire a specific lawyer: after receiving the fee, the People's Commissariat of Justice appointed a defender from among its salaried staff.

Dmitry Kursky, the first Soviet Prosecutor General, People's Commissar of Justice of the RSFSR, and the Prosecutor of the RSFSR. A proponent of a justice system tailored to “the needs of the revolution”

In this form, the Soviet judicial system existed until 1922. Besides abolishing the old system, the court decrees introduced a duality in the justice system: there were revolutionary tribunals to handle crimes against the revolution and people's courts for everything else. There was also the Extraordinary Commission – the infamous Cheka – a security agency with a mandate to carry out repression and the power to execute by firing squad or imprison in labor camps on an administrative basis – that is, without a trial.

Cheka's decisions could not be influenced by any defenders. Revolutionary tribunals, whose jurisdiction was interpreted very arbitrarily, also allowed defense only in exceptional cases. Defense attorneys had broader access to the people's courts, but the bar had been almost destroyed by then. Many lawyers died of starvation or were killed in the lawlessness of the Civil War; some were forced to change their occupation, and about 1,700 attorneys emigrated.

Eugene Huskey estimated that of the 13,000 attorneys in 1917, approximately 650 remained active in 1921. To compare, the Russian Federal Bar Association counted 75,504 practicing lawyers in 2020, and the populations of the Russian Federation and the 1920s’ USSR are almost identical.

Of the 13,000 Russian attorneys in 1917, only about 650 remained active in 1921

The division of Soviet legal practices into counter-revolutionary and all others persisted until the Khrushchev Thaw in the early 1960s. Counter-revolutionary crimes always implied special treatment – that is, mass terror executed by specialized punitive bodies. In the Criminal Code, such crimes were singled out in a separate chapter in which the state openly proclaimed the courts to be a means of squashing political opposition (in Russia’s current Criminal Code, there are no purely “political” articles, so the political motivation of an investigation requires proof in today's Russia).

The amended version of the Decree on the People's Court dated October 21, 1920, aggravated the plight of the bar. The decree abolished the boards and introduced labor duty for lawyers. All independence was gone.

The NEP and the revival of the bar

This setup did not last, as the young nation soon entered the period of liberalization known as NEP – the New Economic Policy. The de facto ban on legal practice led to the emergence of “underground lawyers.” While they couldn’t argue cases in courts of law, they offered counseling and drafted paperwork for a fee. Unable to beat the phenomenon, the Bolsheviks decided to join it – especially since the government allowed certain elements of capitalism. The legal nihilism characteristic of the Civil War period gave way to a more regular approach advocated by champions of legitimacy. Russia adopted its first-ever criminal and civil codes, along with corresponding codes of criminal and civil procedure. Revolutionary tribunals were abolished, and a unified system of people's courts and higher instances was introduced instead.

The de facto ban on legal practice led to the emergence of “underground lawyers”

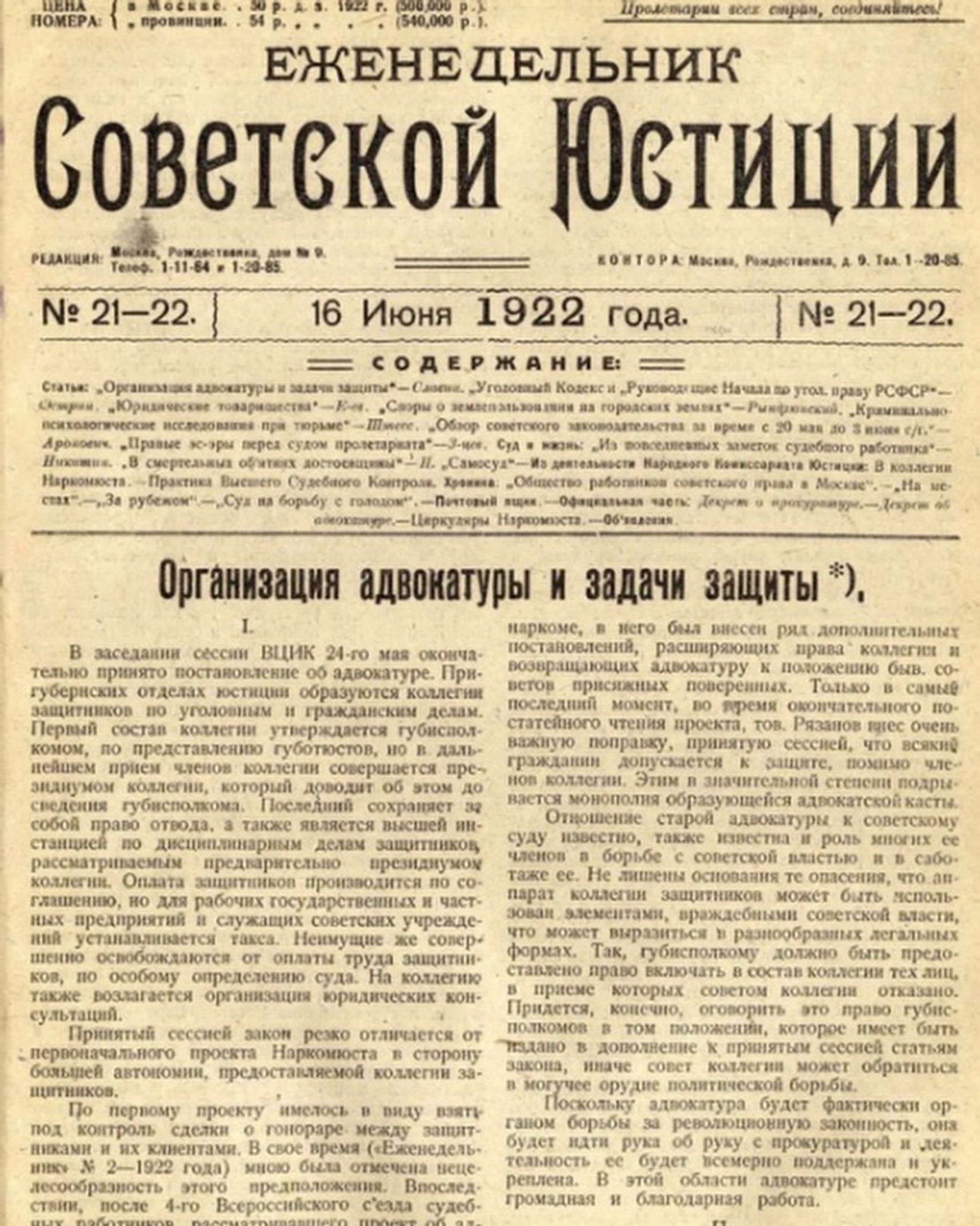

May 26, 1922, saw the adoption of the Statute on the Board of Defenders, which offered the boards greater autonomy: each board elected the bureau, which made decisions on admission to the board. The executive committees of the Soviets, prosecutor's offices, and courts were to “supervise” the boards’ activities, but the statute did not specify the exact procedure. Private practice was also allowed, but “collectives of defenders” remained a preferable modality. By some estimates, the number of attorneys had grown to 2,800 by early 1923, with lawyers beginning to trickle back to their trade. With minor changes, the relatively independent version of the bar existed until 1939.

The weekly publication by the Soviet justice system that released the Statute on the Board of Defenders

However, Soviet defense attorneys were never referred to as “defense counsels” before 1939. These were either “defenders” or, more frequently, CheKaZe (the Russian abbreviation for “members of the Board of Defenders”). The word “attorney” was associated with imperial sworn attorneys and the bourgeoisie – and such was the stereotypical image of lawyers in Soviet mass culture. A vivid example is the nameless character noted in the credit as “Lawyer” and brilliantly played by actor Boris Zhukovsky in Vyborg Side (New Horizons), a 1939 Soviet blockbuster by Grigory Kozintsev. The Vyborg Side is the final part of the trilogy about the heroic Maxim, who fights to install order in the new revolutionary conditions. Among the spontaneous forces taken on by the protagonist are the pogromists, whose inglorious but certainly memorable defender is the corrupt “Lawyer.”

The birth of Stalinism and purges in defense boards

Although the legislation on boards of defenders was barely amended, their practice underwent drastic changes. In the late 1920s, the rivalry within the Communist Party escalated, ending in the unquestionable victory of Joseph Stalin, whose theory of intensifying the class struggle in the transition period required strengthening the state and its legal framework. The state began to structure its institutions in a centralized and hierarchical manner, finalizing its bureaucratic procedures and controls.

The period of the First Five-Year Plan was marked by increased repression and chaos, accompanied by staff turnover, rapid urbanization, and famine in many parts of the USSR. The defense boards were also impacted by these developments. In the late 1920s, the “purges” began. Defense counsels were forced to join collectives. The independent Moscow Board of Defenders, which in 1929 had 1,200 members, had shrunk to only 600 in 1932.

Before the Soviet Union entered World War II in 1941, the bar had survived six purges. Notably, the purges affected not only defenders whom the authorities found “unreliable” but also those who’d become the object of real (and legitimate) complaints due to their incompetence. A vicious circle emerged: the government sought to attract more Communists to the bar, solely because of their loyalty to the party, but then had to «weed them out» because of their low qualification. Russian researcher Alexander Kodintsev cites curious statistics. In 1939, shortly before the bar was reorganized, only 37% of lawyers on the Moscow Board of Defenders had a higher education. Some were downright illiterate. Thus, lawyer Loboda from Sverdlovsk made 83 spelling mistakes in a single complaint, lawyer Chernenkov from Krasnoyarsk made 75 mistakes, and their colleague Stekker managed to make 38 mistakes in a 100-word statement.

Lawyer Loboda from Sverdlovsk made 83 spelling mistakes in a single complaint

As a consequence, the country suffered from a catastrophic shortage of lawyers. Eugene Huskey believes that only 10% of cases were tried with a defense counsel in the late NEP period. Alexander Kodintsev cites data from the People's Commissariats of Justice of November-December 1938, already after the Great Terror: 816 districts of the USSR didn’t have a single lawyer.

Legal nihilists vs. champions of legitimacy

During the first Five-Year Plan, the ideas of legal nihilism were rejected, and the proponents of the “revolutionary sense of justice” were even held partly responsible for the failures and extremities of the previous years. Nikolai Krylenko, a highly influential legal nihilist who occupied the post of People's Commissar of Justice first in the RSFSR (from 1931) and then on the national level (from 1936) pushed for abolishing the Criminal Code altogether. In 1938, he was arrested and executed on falsified charges as a member of a conspiracy. With his demise, legal nihilism gradually faded into the background.

Nikolai Krylenko, Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army after the October Revolution of 1917, People's Commissar of Justice of the USSR

Meanwhile, the “champions of legitimacy,” headed by Andrei Vyshinsky, the chief prosecutor of the RSFSR and then the entire Soviet Union, were gaining strength. Vyshinsky, who’d also practiced law before the revolution, wholeheartedly believed in the social benefits of legal frameworks, regular institutions, and established procedures. To strengthen his position, he endeavored to ally himself with the bar. The defense attorneys saw Vyshinsky as their champion. Many willingly began to cooperate with the authorities.

However, such an alliance came at a price. At a meeting of the Moscow Board of Defenders in December 1933, Vyshinsky put forward his understanding of defense in Soviet courts. His report came out a year later as a standalone book. Vyshinsky argued: “A defense counsel’s objective is to keep in mind that the courtroom is the laboratory where public opinion is formed – in other words, where relations take shape and, interlocking with other social and political relations outside the courtroom, grow into a certain political force.” Quite naturally, Vyshinsky's main goal was to transform the bar into a political ally of the Soviet government. And the bar generally accepted the new terms.

Vyshinsky's personality is closely linked to the show trials that were organized on falsified charges from the late 1920s. In these trials, the mandatory presence of the defense and observance of the procedure were major credibility factors. However, the attorneys never challenged the prosecution. Their purpose was to remind Soviet society that it was “humane” and “merciful.”

The Communist Party and the bar: Attempted control

Since lawyers weren't technically public servants, the ruling party needed to control them somehow, so it introduced as many Communists as possible into the bureaus of the boards of defenders. The Communist Party did not abandon these attempts throughout the entire existence of the Soviet bar, but even at the height of pressure in 1939, Communists didn’t account for more than 25% of the bar.

Even at the height of pressure in 1939, Communists didn’t account for more than 25% of the bar

The first reason was the resistance to this infiltration from lawyers, as former imperial sworn attorneys still made up the core of the bar. The Moscow Board of Defenders was even known to feature an almost anti-Communist faction, which actively sought to democratize elections to the boards. Some boards practiced secret voting, thus preventing Communists from getting into the bureau.

The second reason was the nature of the Soviet nomenklatura – the hierarchy of top-ranking bureaucrats. Party bodies were the crucial social elevator in the Soviet Union. By contrast, the bar was constantly vilified in the press and withered under the pressure of the Soviet justice system. Joining the bar seemed like a strange choice for a career-oriented Communist. Granted, they could be driven by a passion for the law or considerations of financial gain, as lawyers were making decent money.

The terror and the bar

The spring of 1937 – the threshold of the Great Terror – saw a surge in repression against Red Army commanders. In Directive No. 863 of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks dated July 3, Stalin obliged party bodies to prepare lists for execution by firing squad and to form troikas (groups of three officials) to pass sentences without a trial. On July 30, together with NKVD Order No. 00447 and the kulak operation (the elimination of wealthy peasants), the period of Great Terror, or Yezhovshchina, began, and lasted until November 1938. Most scholars of the period are unanimous: of at least 1.2 million people arrested, about 700,000 were executed. Every day, the Soviet Union executed about 1,500 people.

The Great Terror was largely enabled by pre-existing investigative procedures. Repression followed the algorithm of the criminal process – minus the committal for trial and the trial itself. The court of law was replaced by special bodies with extraordinary powers: troikas, special meetings, and so on. Preliminary investigations were accompanied by intimidation, torture, and mass falsifications but were formally preserved. The Great Terror, a pogrom packaged in investigative and bureaucratic form, was an unprecedented campaign against the country's own population.

The Great Terror was largely enabled by pre-existing investigative procedures

The system left almost no room for lawyers because the Code of Criminal Procedure suggested the input of defense only at the stage of judicial investigation, which had been excluded from the terror procedure. As for the pre-trial investigation, the participation of a defense counsel was not envisaged at all. Oddly enough, lawyers still had a few options for influencing the process – either bypassing the standard practices of terror or integrating into them.

Composer and pianist Tikhon Khrennikov recalled how his two brothers had been arrested. He filed complaints wherever he could and enlisted influential acquaintances to file even more. Eventually, his brother Nikolai's case was heard by a court, not an extrajudicial body. The family got the opportunity to hire a defender. Khrennikov hired Ilya Braude, a renowned lawyer who often defended “enemies of the people” in public trials.

The outcome of the process was extremely favorable: prosecution witnesses refused to testify right on the stand, so Nikolai was immediately released. It is unclear whether it was Braude's effective defense or his overall credibility that played the key role, but this case demonstrates how the bar could contribute to the resistance to terror.

Apart from representing “political” defendants in court, Soviet lawyers could resort to semi-official formats of legal defense. For this kind of defense, connections played a bigger part than an understanding of procedures, but some chose professional lawyers as their champions. The daughter of lawyer Vladimir Rossels recalled that her father had once been approached by the wives of four agricultural specialists: three agronomists and a zootechnician.

Apart from representing “political” defendants in court, Soviet lawyers could resort to semi-official formats of legal defense

Rossels reviewed the case and drafted a supervisory complaint – a special type of complaint filed on the prosecutor's behalf. Technically, the prosecutor's office was obliged to review the justice of verdicts but it never did in times of terror. Instead, the supervisory body joined the organizers of mass repression since most troikas also included prosecutors.

Rossels took his complaint to Vyshinsky, with whom he was on good terms. Vyshinsky acted surprised and submitted a protest on his own behalf, after which the men were released. This case served as inspiration for Ilya Zverev’s short story “Defender Sedov,” which was adapted for the screen by director Ilya Serov in 1988.

During the Great Terror, less than 10% of political cases were considered by the judiciary. But even in these cases, defendants could not always hope for legal representation. The case of Mikhail Astashin was a rare exception.

The Astashin case: A Great Terror trial

In September 1937, 63-year-old yard keeper Mikhail Astashin faced charges from the state: he’d allegedly said in the presence of the tenants that villagers were starving and that Stalin knew nothing about it, being surrounded by Jews. He was also accused of hiding his purported kulak origins. Later, the list of his sins was expanded to include “defeatist sentiments”: Astashin allegedly frightened local children, saying the Japanese would come and beat them as they were now beating the Red Army (referring to the constant clashes between the two armies in the Far East).

Finally, Astashin complained about queues in stores and doubted the guilt of Pyatakov, the unfortunate defendant of one of Moscow's show trials. All this fell under Article 58.10 – “counter-revolutionary propaganda.” Paragraph ten was the most broadly applied and at the same time the most controversial part of Article 58: from the legal perspective, the key to the corpus delicti was counter-revolutionary intent – that is, a subjective component that was difficult to prove or disprove.

Proving counter-revolutionary intent was key to the corpus delicti

Astashin's trial took place on August 5, 1938. The case was heard under unusual circumstances, without a prosecutor, because the prosecution had the right to remove itself from cases seen as straightforward. Similarly, the court could keep the defense out of the proceeding, but it chose not to. As a result, the case was heard without the prosecution but with the defense.

The first important fact that needed proving is that the defendant was not a kulak. Lawyer Guliyev built his defense as follows. Astashin was no kulak since the certificate of his social origin had been compiled by a man who’d since been arrested. House manager Gavrilov, who’d reported Astashin, was acting out of self-interest because he had his eyes set on Astashin’s room.

Finally, Astashin had never expressed dissatisfaction with the Soviet authorities or said anything essentially counter-revolutionary because food shortages could have various causes. The defender summarized: “I tend to agree that Astashin is a whiny philistine, but I disagree that he is a counter-revolutionary.”

There’s hardly any evidence in the descriptive part of the sentence, but the court decided that Astashin was guilty on all charges because witnesses said so, and sentenced him to seven years in correctional labor camps. The story could have ended there, but Guliyev did not give up. Almost immediately he filed a cassation appeal to the Supreme Court of the RSFSR, which rejected it.

A year later, the USSR Supreme Court considered the complaint and sent the case for an additional hearing. At the new trial on April 11, 1940, Guliyev chose a completely different tactic: Astashin was to deny all charges. In the new version, he's no longer a “whiner” but a victim of slander. Meanwhile, the witnesses, perhaps for fear of facing perjury charges, assured they hadn’t personally heard those “dangerous conversations.” The court found their earlier testimonies unreliable and acquitted Astashin.

What secured the favorable outcome of the case? The case never reached national security agencies and was never considered by a troika or another punitive body, which would have predetermined a tragic outcome. Instead, it was heard in a court of law, which means the defendant had a chance for review and defense. The lack of publicity in Astashin's case also explains why punishing him was not a matter of principle for the Soviet authorities.

A persistent enough lawyer could save his client, so it was Guliyev's stubbornness in taking the case to the highest court that played a crucial role. The change in the court's position may also have been caused by the end of the Great Terror: judges were less afraid of being objective.

Importantly, the bar wasn't immune to repression, and many defense lawyers were executed or ended up in the Gulag. The fate of repressed lawyers from the Moscow Board is the subject of researcher Dmitry Shabelnikov's project “Defenders Whom No One Protected.” As he estimated, about 400 lawyers in the capital alone fell prey to the Great Purge.

The war and the bar

In 1939, the bar underwent another reform. Defenders were renamed attorneys and collectives were renamed legal clinics. Aside from cosmetic changes, there were also significant ones: boards of attorneys officially reported to the Commissars of Justice, and fees were now paid under the approved instructions. Private practitioners of the law came under a harsh attack. Private practice only remained possible for a handful of renowned, trusted attorneys deeply embedded into the Soviet nomenklatura – such as the aforementioned Ilya Braude. The legal profession finally assumed the form and the name it would retain until the Khrushchev Thaw in the early 1960s.

Private practice only remained possible for a handful of renowned, trusted attorneys

When Nazi Germany attacked the USSR in 1941, martial law was imposed on a large part of its territory, which implied, among other things, a reformatting of the judiciary. In some regions, civil courts were abolished and their functions were transferred to military tribunals, whose verdicts could not be challenged in cassation (the only way to challenge a verdict in the USSR, where appeals did not exist). This way, the bar had no sway over the investigation since the defense was not admitted to the hearings.

Still, some attorneys managed to find a way around it. One such ingenious lawyer was Elena Romanova, a member of the Moscow Board of Attorneys. Romanova received permission from the 3rd Legal Clinic to work in the archives, where she looked up cases of people convicted of counter-revolutionary propaganda, studied them, and drafted complaints.

She is unlikely to have received such an assignment from her superiors, so we can safely assume that she was driven by genuine personal interest. This is a good illustration of a lawyer's work in a challenging wartime setting, when the Soviet government once again transgressed the law, fearing its own population.

The Artemenko case: A wartime trial

Andrei Artemenko, the chief engineer at a defense plant, was arrested on April 29, 1942, on charges of mismanagement in a time of war (Article 128, aggravated by Article 132). In his capacity as chief engineer, he allegedly allowed the use of defective parts in the production of mortars deliberately; as a result, 150 mortars had to be recalled from the army.

Artemenko denied all accusations until an aggravating circumstance was discovered: his diary, in which the defendant, according to the investigator, expressed political sentiments “unbefitting of a Soviet citizen,” such as: “A lot of codswallop, bragging from top to bottom. We often heard lengthy statements about waging war on foreign territory, countering the onslaught of multiple capitalist states. Meanwhile, we are struggling to resist Germany alone. These reflections are inspired by the shameful panic that took place on October 15 at the order of the Party and Soviet organs, which caused Moscow's industry to stop its work.”

The investigation lasted about a month, and in June 1942, Artemenko was brought before the Military Tribunal. He was sentenced to five years on the original charge and seven years for the diary (Article 58.10). The aggregate sentence amounted to seven years. Even during the war, Soviet courts doled out harsher punishments for a diary with “counter-revolutionary ideas” than for sabotaging military production.

Even during the war, Soviet courts doled out harsher punishments for a “counter-revolutionary” diary than for sabotaging production

Romanova took an interest in Artemenko’s case. What caught her attention was the fact that Artemenko’s mismanagement charges were backed only by witness testimony, whereas procedure required expert examination to substantiate such accusations. On the “superior” counter-revolutionary charge, the procedure was grossly violated as well: the court neither questioned witnesses nor read out the diary, which meant the verdict didn't meet substantiation requirements.

Romanova decided to review Artemenko's case and file a complaint against the verdict. As befits a Soviet lawyer, Romanova did not question the significance of Soviet authority but used all the eloquence she could muster to explain her new client's motivation:

“In these words, Artemenko is revealed as a man who deeply feels and experiences the horrors of war, who believes in our victory, believes in the end of the war, and is eagerly awaiting the post-war life and his return to his favorite work and his family.

At the time when Artemenko made these records, his family was outside Moscow, he appears to have had no close friends among his colleagues, and therefore, put his experiences on paper. However, when analyzing his records, it is difficult to conclude that Artemenko is an anti-Soviet individual, that he is socially dangerous and needs to be isolated.”

It was impossible to file a cassation in the Moscow Military District during the war, so Romanova wrote a complaint to Sergei Romanovsky, the chairman of the Military Tribunal, detailing the circumstances of the case. Romanovski was her only option. As chairman of the tribunal, he had the power to review cases considered by his department.

The Prosecutor's Office also had the right of supervision, but Romanova had a history of rejected complaints there. Her gamble played off: the chairman filed a protest using Romanova's arguments, and on December 21, 1942, the Military Tribunal annulled the sentence on the counter-revolutionary charges and submitted the sabotaged production case for further investigation.

Artemenko was first held in the correctional labor colony in Kryukovo outside Moscow, then was transferred to Taganskaya Prison. On February 22, 1943, he was drafted into the army, and his case was suspended – which was also rare. In March 1943, Artemenko was shell-shocked, and after recovery was recognized as fit for non-combat service. He served in the Red Army until the end of the war and was awarded the Order of the Red Star. Due to his wartime merits, his case was finally dismissed, and all charges were dropped.

Of course, Andrei Artemenko's unusual fate is, to a large extent, the result of his own efforts, courage, and luck. But Elena Romanova holds credit for at least some of his good fortune as she found the strength to challenge a politically motivated sentence even in a war-torn totalitarian state.

Implications of the regime's pressure on the legal system

The history of the Soviet bar aptly illustrates the paradoxical and controversial nature of the Soviet Union's legal system. On the one hand, the bar experienced the brutality of the system, especially during periods of repression and political purges. However, some examples show that lawyers’ professionalism and persistence could be decisive and lead to acquittal or revision of cases. These cases illustrate the importance of the bar as a civil rights defense mechanism.

However, despite some successes and courageous representatives, the institution of the bar could not escape involvement in the Soviet political agenda, which significantly hampered its development and weight as a public institute. During the late Soviet era, when the state pressure somewhat eased, the bar never fully recovered from the consequences of Stalinism, although it did become a prominent participant in the human rights movement.

During the democratization period of the 1990s, the bar made multiple attempts to integrate into the new legal landscape and assume a meaningful position in society but failed to secure the level of influence it had during the revolutionary changes of the early 20th century. Therefore, if the impact of a political regime on the legal system is long-lasting and profound, its effects can reverberate across institutions for decades.