On March 6, three merchant sailors were killed in the Gulf of Aden by a Yemeni Houthi missile attack against the ship True Confidence. These were the first crew member deaths since the group began targeting commercial vessels in the Red Sea in October 2023. Yemen's Houthis, who have been launching rocket attacks for more than a month, were until recently a despised and persecuted minority in their own country. Now they are trying to return Yemen to a modern authoritarian version of the largely medieval, albeit peaceful, way of life that existed in the country a mere forty years ago, says journalist Andrei Ostalsky, who lived in Yemen in the 1980s. The Houthi regime, which has seized power in most of Yemen, represents about 15% of Yemenis, but dictates its will to the rest of the population, brutally cracking down on homosexuals and dissenters. Yemen faces famine and devastation, which the Houthis blame on outside forces, while widespread snitching has made ordinary citizens fearful of their neighbors.

The authorities of the so-called Islamic State cracked down ruthlessly on those suspected of homosexual orientation. They were sentenced to stoning, but more often subjected to the relatively humane execution of being taken to the roof of a tall building and thrown off — a few seconds of pure horror followed by immediate death. You are happily forgotten forever before you even feel the pain. The Yemeni Houthis have no respect for such humanism. They sentence anyone suspected of being a homosexual to beatings, or even to the longest and most painful form of torture — literal crucifixion.

A man crucified in Yemen

Source: MEMRI TV

In early February, Amnesty International reported that nine gay men were sentenced to death in the city of Damar: seven of them were sentenced to stoning and two — who seem to have particularly angered the judge — to the ancient Roman method. Another 23 people were sentenced to long prison terms for “immoral behavior.” Meanwhile, the conditions in the Houthi prisons are such that those 23 might envy those executed.

In turn, AFP reported that in Ibb province, 13 students were condemned to death because of their homosexual orientation. But these are only isolated cases, fragments of a picture that remains invisible to the world — just the tip of the iceberg. Similar sentences are being handed down in all other cities under Houthi control, including Sana'a, Hodeidah, and Taiz. This is clearly a large-scale campaign to eradicate the “sin of sodomy,” carried out at the request of the Supreme Political Council and most likely with the approval of the authoritarian ruler, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi. In Yemen, an anonymous report is sometimes enough to incriminate a person.

Under Houthi rule, any expression of dissent is generally suppressed. The security services crack down on protests. Activists and journalists are regularly detained and tortured. All ministries and agencies are staffed by Houthi appointees who subordinate the administrative system to their political goals. An atmosphere of fear is cultivated in the country to enforce obedience. Whistleblowing is in full bloom, and people have become afraid of their neighbors, frequently speaking in hushed tones to avoid being overheard. Overall, it seems that the Houthis have succeeded in building a police state in Yemen.

Who are the Houthis?

But who are they and where do they come from? The Houthis are not a nationality, a tribe, or a religious community. They are supporters and obedient enforcers of the al-Houthi family of the Banu Hamdan tribal confederation, which has long inhabited the northwestern province of Sa'ada. This family was able to capitalize on the protests of the local people, who had long been discriminated against by Yemen's previous rulers. This, then, is the story of how the oppressed became the oppressors.

The Houthis are descended from Shiite Zaydis, who make up about a third of the country's population. But not all Zaydiites support al-Houthi — only about half do. For many other Zaydis, the Houthis are impostors, a mafia that has seized power by breaking with the most important Zaydi traditions while grossly distorting others for their own selfish ends. But now it can only be whispered about — otherwise it will be reported.

In other words, the regime that has seized power in most of Yemen represents about 15 percent of Yemenis, but dictates its will to the rest. Yet history is replete with examples of how a minority, if it acts decisively, devoutedly, and above all ruthlessly, can gain unlimited power over the entire population. One need only recall the Bolsheviks.

Two years in Yemen

When I went on a long business trip to North Yemen in the early 1980s, my Arabist friends — those who had had a glimpse of the country — were unanimous in saying that they could only envy me: here are the real Arabs, the true, unspoiled origins of Arab culture and the unspoiled Arabic language.

What I saw in Sana'a, the capital, was strange to the point of being shocking. In the almost two years I worked there, I was never able to fully adjust: you cannot be painlessly transported to the “natural” Middle Ages — something like a cultural decompression sickness stands in the way. Some got over it gradually, but I was never cured; this strange environment made me feel rejected, mixed with permanent amazement. But, oddly, it also filled me with respect. What I saw was an authentic, and, in its own way, great medieval civilization.

The architecture alone was worth it! Tall clay houses, just under thirty meters (close to 100 feet) tall, with beautiful white patterns of limestone, called “the world's first skyscrapers” by many — as some of them were built a hundred, two hundred, or even three hundred years ago. This clay is specially dried in the sun and therefore surprisingly resilient to both wind and earthquakes.

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

The “world’s first skyscrapers” in Yemen

Yemeni women, known as the most beautiful women in the Arab world, are dressed all in black, in a niqab, faces fully masked but for a narrow slit for the eyes, leaving only a hint of their rare beauty. On several occasions, however, a girl walking down a narrow street took off her mask for a second and even gave me a wink.

Women in Yemen

Women in Yemen

Women in Yemen

Men wear white dishdashas — an extremely comfortable garment in a hot climate. They usually have a jambiya on their belt — a terrible curved dagger, weapon and jewelry at the same time, both a symbol and a fetish, passed down from father to son. The richer and more noble the clan, the more complex and exquisite the patterns on the scabbard. Kinship, family, tribe and clan honor — these are the main values that determine the behavior and complex relationships between people here. And the 30% lack of oxygen in the high mountains of Sa’naa has a strange effect on the brain — no wonder that something strange begins to happen to the mind. At night, you begin to see the same things you see during the day: a flicker of clay skyscrapers, black niqabs for women, and white dishdashas for men. Then narrow streets, then wild deserts — there are none of the usual signs of modern life. Strange ways of speaking and moving, strange, incomprehensible unwritten laws. Getting used to it is impossible, or at least very difficult.

The person who came closest to this ideal was the outstanding Soviet Arabist Pyotr Gryaznevich, who had a profound knowledge of Yemeni culture, manners, and psychology, as well as of the local dialect of Arabic, which is surprisingly close to the classical one seen in the Qu’ran. It was said of Gryaznevich that he became more Yemeni than the Yemenis themselves. Even in his St. Petersburg apartment, he wore a dishdasha. Some mutual acquaintances, however, twiddled their thumbs: they said he might be a genius, but to be so deeply steeped in the medieval mentality is to go a little mad — at least from the point of view of a modern European.

What those who defend the inhumane practices of the Houthis say is that Yemen has never known anything like democracy and respect for human rights in its history. And I am a living witness that this is true. The criteria and values of modern European society are not compatible with the local feudal and tribal order. But the traditional society that existed there in the latter half of the last century was equitable, stable, and even relatively humane. The country was poor, but there was no mass starvation or shortage of drinking water. Yes, it was by no means a constitutional state, but it still had laws, most of which did not allow for abuses or excesses.

Yemen has never known anything like democracy and respect for human rights in its history

The Middle Ages come to life

A strong factor was medieval ethics and a kind of public opinion that we do not fully understand: tribal clans could protect their members from lawlessness. You couldn't kill on a whim, you couldn't starve children or be openly cruel to women. There was a notion of fairness and proportionality. If you did not fight with the authorities, the authorities left you alone and were even willing to provide (or try to provide) you with security and the ability to feed yourself and your family.

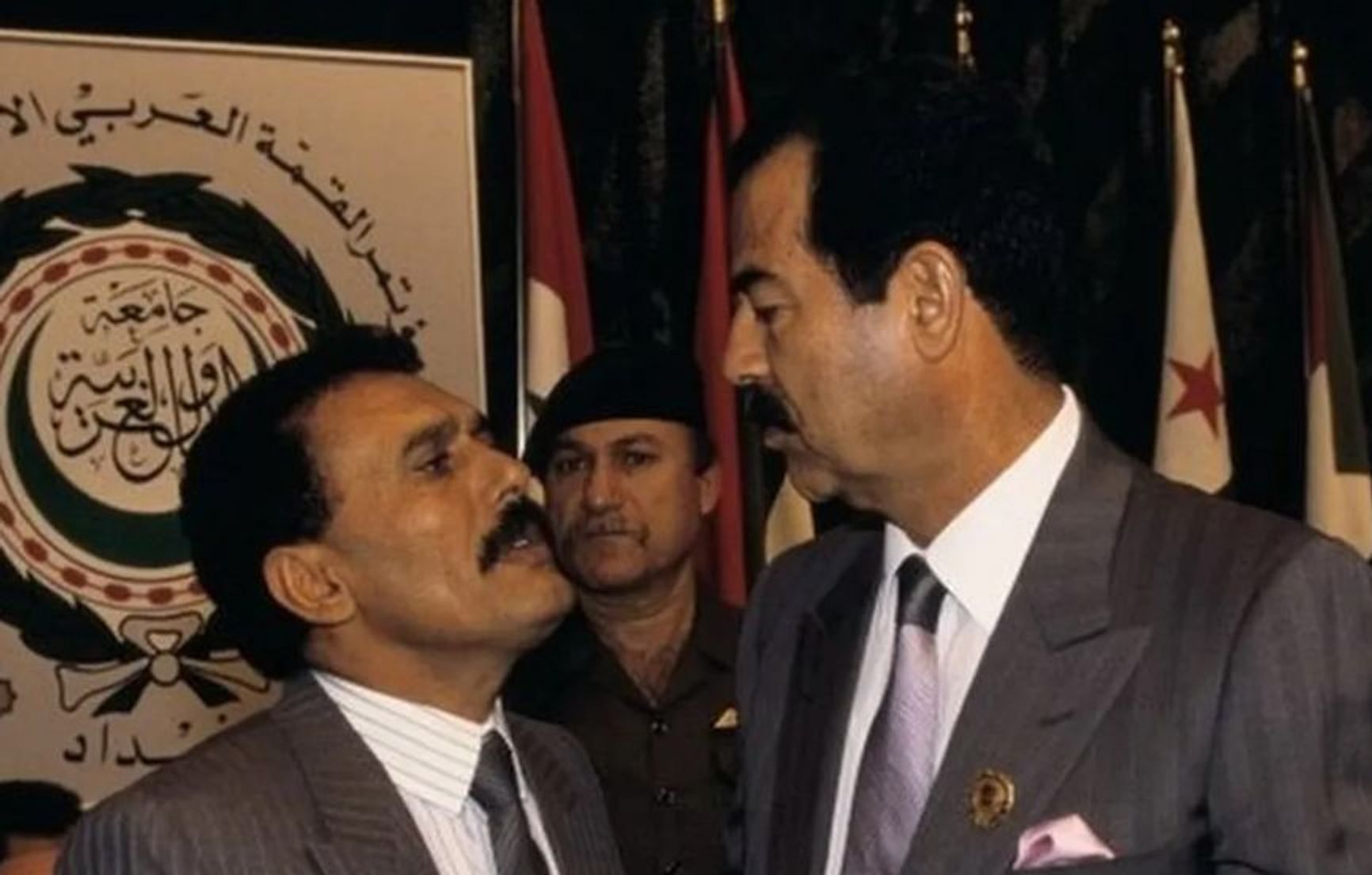

At the same time, the political system was authoritarian in nature, and President Ali Abdullah Saleh was practically a dictator, but not an absolute one: he still had to reckon to some extent with this very medieval, tribal public opinion. Parliament was by no means a place for debate, but there was still a certain independence of the Sharia court (on the same condition that you were not going to sue the supreme power).

Ali Abdullah Saleh and Saddam Hussein

In short, you could travel around the country in peace — if you avoided areas dominated by wild and proud independent tribes, where you could have easily been taken hostage. But in other places, one could have walked without looking back, spoken without lowering one's voice, and communicated at ease with the locals. For them, an exotic foreigner was new and aroused sincere and usually benevolent interest. This was in stark contrast to many other Arab countries, particularly Iraq, where I spent three years and was constantly provoked into silence by the local security services. And free communication with the Iraqi people was out of the question — it was deadly, especially for them.

In short, Yemen did not have an atmosphere of crushing, clammy fear like the one Saddam had created in Iraq or the one the Houthis are now creating in the country. The Saleh government, while not abandoning economic cooperation with the USSR, was still oriented toward the United States and other Western countries that supported Sana'a as a counterweight to Soviet influence. The USSR, on the other hand, turned South Yemen into its own semi-protectorate, claiming to have established some semblance of socialism there — in other words, failing to solve the problem of chronic shortages. In the north, however, the rial was freely exchanged for all Western currencies and capitalist plenty prevailed.

A temporary Sunni triumph

In those years, the Sunni Muslims were the country's privileged religious community. In September 1962, they ousted the Shiite Zaydis from power in a military coup — officially termed a “revolution.” Before that, the country had been a Shiite state, an imamate, for more than a thousand years — a unique case in the Arab world. But by the early 1960s, Sunnis had become the majority of the population. They represented the emerging petty bourgeoisie and a kind of urban middle class, and they also held a dominant position in the army. Therefore, the transfer of power to them seemed inevitable and even progressive. The Zaydis remained in the majority only in the mountainous regions of the north, especially in the province of Saada on the border with Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, the Zaydis as such were considered to be very relative Shiites, and their dogma and rituals were so strikingly different from those of Iran that it was difficult for the ayatollahs to regard them as fellow believers. The key difference was that the Zaydis did not recognize Iranian mysticism, with its belief in a hidden Imam, a Messiah who would appear and defeat the false prophet Dajjal and all of Islam's enemies and establish a just rule over the entire earth. They also did not recognize the authority of the ayatollahs. In general, Zaydi theology was considered very tolerant and liberal, and in some respects it was the successor to the theology of the Mu'tazilites, who believed in free will and considered reason to be the criterion of faith. They were once associated with unfulfilled hopes for an era of revival and enlightenment in the Islamic world.

The fact that the Houthis have now embraced Tehran and become loyal allies of the ayatollahs is considered heresy and treason by classical Zaydi theologians. Now Sana’a and other Houthi-controlled cities are festooned with green flags — replicas of those in Iran. There are also portraits of Khomeini, as well as of Qassem Soleimani, who commanded the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps' most important unit, the Quds Force, until his assassination by the U.S. in 2020. And the Houthis’ official slogan is everywhere, almost identical to a similar motto from revolutionary Iran: “God Is the Greatest, Death to America, Death to Israel, A Curse Upon the Jews, Victory to Islam!”

A Houthi demonstration with posters and placards reading: “God Is the Greatest, Death to America, Death to Israel, A Curse Upon the Jews, Victory to Islam!”

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Zaydis were considered a second-class people in northern Yemen. Sunni authorities disparaged them, referring to them with undisguised contempt as “semi-literate, dumb peasants.” There is no doubt that they were discriminated against everywhere except in Saada, where they were a clear majority and where the viceroys sent from Sana'a had only nominal power. The Banu Hamdan elders ruled here, and the real levers of self-government were in the hands of a few Zaydi families. The al-Houthi family was one of the most influential. Its men had long been claimants to the title of seyyid, or direct descendants of the prophet Muhammad. The respected theologian Seyyid Badruddin, who had eight sons who became the heart and driving force of the Houthi movement, was the head of the clan at the end of the twentieth century.

The Houthis return

The most fiery revolutionary, the Yemeni Lenin, was Hussein al-Houthi. His theological credentials seemed questionable. But what he lacked in knowledge he more than made up for in charisma, fanatical belief in his own leadership, fearlessness, and ruthlessness toward his enemies. With the force of a chieftain, he promised the Zaydis sweet revenge for decades of repression and discrimination, the return of power to all of Yemen, and the freedom of the country from the “damned infidel” who, he claimed, had turned Ali Abdullah Saleh into a puppet. Hussein organized a series of uprisings that shook the Sunni central government and created a powerful militia called Ansarullah (“Allah's Forces”). He became President Saleh's most important and dangerous enemy, and was hunted down with a bounty of tens of thousands of dollars on his head — colossal by Yemeni standards. In the end, the fearless Hussein fell into a trap and was killed.

The poster shows Hussein al-Houthi (left), Abdul-Malik al-Houthi (right) and their father Badreddin al-Houthi (center)

But the Yemeni Lenin was to be replaced by the local Stalin — one of Hussein's brothers, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi (also known by the revolutionary alias Abu Jibril). It is he who now rules with an iron hand over the greater part of northern Yemen, and who presides over a campaign of mass repression and ideological indoctrination. In schools, his portraits hang on the walls, students are forced to learn the facts of his and Hussein's heroic biographies and, of course, to chant the same slogan several times a day: “God Is the Greatest, Death to America, Death to Israel, A Curse Upon the Jews, Victory to Islam!”

The Houthis' claim to be the selfless protectors of all Muslims (and especially the Palestinians), their willingness to fight the West to the death by blocking international shipping in the Red Sea — all this is aimed primarily at an internal Yemeni audience. They remember that they are an absolute minority, and they cannot afford to forget that they have to win the battle for the minds and hearts of the impressionable youth, including the Sunni youth. To some extent, they are succeeding. But this play has a second important audience: the ayatollahs in Tehran. The Houthis receive weapons, drones, missiles, financial, and other support from Iran — mostly through Lebanon's Hezbollah.

Even with Iranian help, the Houthis probably would not have succeeded in taking Sanaa and other major cities in Sunni areas were it not for the history of former President Saleh. In 2012, after decades of one-man rule, amid massive Arab Spring protests and under pressure from Saudi Arabia, Saleh was forced to step down. He held a grudge, and in order to return to power, he formed an alliance with his worst enemies: the Houthis. Saleh was backed by part of the army, and as a result, this strange, impossible alliance managed to capture the capital, along with several other cities. Saleh thought he would use the Houthis and then deal with them. But it turned out the other way around. Abdul-Malik confirmed his rather Stalinist cunning — in 2017, the Houthis killed Saleh. With the loss of their leader, the soldiers were confused. Some of them scattered, while others decided to join the winning side.

Screenshot from a video showing the body of Ali Abdullah Saleh

In 2015, alarmed by the prospect of an Iranian satellite near its borders, Saudi Arabia formed a coalition that included Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Qatar, Kuwait, Morocco, the United Arab Emirates, and Pakistan. But these states did not want to fight actively on the ground and suffer casualties. Instead, they opted for intensive bombing of Houthi positions from the air. This air campaign went on for nearly seven years. Bombings and missiles often hit the wrong targets, damaging infrastructure as well as schools and hospitals. Civilian casualties were high. Eventually, the Saudis and their allies withdrew, realizing that this was not the way to achieve the war's goals. The Houthis made excellent use of the bombardments for propaganda, rallying a large segment of the population against foreign interference and the indiscriminate brutality of the interventionists.

Although the bombing has long since stopped, the Houthi authorities continue to blame mass starvation, severe shortages of drinking water, garbage in the streets, and frequent shortages of fuel and electricity on the bombing, shifting the blame for the largely self-inflicted devastation onto the Saudi coalition. And a significant part of the population believes them. The new government also emerged as the main defender of the Palestinians after the October 7 Hamas attacks. Moreover, the West seems incapable of dealing with the Houthis, who are threatening to paralyze the freedom of international navigation and thus condemn the world to another economic crisis. Many Yemenis are unwillingly admiring this, and Tehran and Hezbollah are applauding and promising to step up their support.

The bombing has long since stopped, but the Houthis still shift the blame for mass starvation and devastation to the Saudi coalition

But the Houthis themselves realize that they are incapable of running the state on their own — they simply lack sufficiently capable personnel to deal with the problems of transportation, logistics, procurement, and energy supply. That is why, in the manner of the Bolsheviks, they have had to settle for the temporary use of specialists from the old regime at all levels of government. The real power remains in the hands of a small circle — the al-Houthi family, their relatives, and friends. (For example, the nominal head of the supreme political council, President Mahdi al-Mashat, is Abdul-Malik al-Houthi’s closest childhood friend.) But already Prime Minister Abdel Aziz Habtoor and key members of his cabinet are technocrats inherited from the previous regime. There is no doubt, however, that once the Houthis have consolidated their power, they will get rid of the technocrats. “The Moor has done his duty, the Moor can go.” Or he will be sent away — or eliminated, if Abdul-Malik so desires.

It is true that the power of the Houthis is not yet consolidated. It seems that Abdul-Malik's older brother Yahia, who has lived for many years in the West, mainly in Germany, could claim the role of the local “Trotsky.” He allows himself to be sharply critical of the policies of his brother and his associates — sometimes even voicing his concerns publicly. His speech exposing corruption in the agency responsible for distributing international aid resonated with many in Yemen. Food that is not stolen often spoils in the agency's warehouses due to negligence. Officials tend to blame the UN’s World Food Program, saying it is the soulless infidels who supply the rotten food. Meanwhile, without international aid, nearly 80% of Yemenis would be condemned to starvation, and many are dying of hunger. Yahia also spoke out in defense of pensioners when Houthi fighters raided the pension office and stole people's savings.

Yahia Al-Houthi

I do not know how long Yahya and other critics of the regime will live. In an environment of mass arrests, extrajudicial executions, and the encouragement of reporting the anti-regime sentiments of one’s neighbors, fear becomes the main and invincible tool.

These events appear to mark a new era — the creation of a dictatorship hidden behind the far-fetched idea of a return to the “true,” “pure” Islam of the Middle Ages. In Russia, meanwhile, an authoritarian power claims to be the protector of “traditional values” and “spiritual bonds,” while Donald Trump leads a movement that seeks to turn back the clock of history. Yemen’s Houthis are, as the kids say, “trending.”