In late March, Vladimir Putin's press secretary Dmitry Peskov promised that Moscow and Yerevan would “survive” the “difficult” times the post-Soviet states are experiencing in their relationship. Armenia, Peskov insisted, “is even more than a brotherly nation, because we have even more Armenians living here [in Russia] than in Armenia itself.” Independent journalist and Caucasus expert Vadim Dubnov notes that Russia’s concept of “brotherly” nations has long been actively exploited by the Kremlin to justify its attempts to limit its former satellites’ sovereignty.

Brotherhood — without a statute of limitations

A 1990s-era tourist slogan in Abkhazia, one of the two Georgian provinces later recognized by Moscow as “independent” following Russia’s military incursion of 2008, read “Relax where you are loved!”

At the time, a Russian visitor to the seaside town of Pitsunda might have thought he was being observant by pointing out the similarly tragic fates of Abkhazians and Serbs, both of whom had suffered through civil wars following the fall of their Soviet patron. However, having been picked up by an Abkhaz official at the airport in the nearby Russian Black Sea town of Sochi, the Russian visitor would have had to pay very close attention if he were to notice his host’s attempt to avert his eyes at the suggestion that Russia had not lost its admiration for both peoples.

Despite Kremlin rhetoric to the contrary, over the past three decades, the relationship between Moscow and Sukhumi has been characterized more by mutual resentment than by fraternal respect. Despite local opposition, in 2022 an old Soviet government building on the blooming Abkhaz coastline was handed over to Russia in yet another example of the Kremlin simply taking from its “brotherly” partner whatever it could grab — from the tiny village of Aibga to “Gorbachev's dacha” in Miuseri (Myussera).

Gorbachev's dacha in Miuseri

Despite Kremlin rhetoric to the contrary, over the past three decades, the relationship between Moscow and Sukhumi has been characterized more by mutual resentment than by fraternal respect. Despite local opposition, in 2022 an old Soviet government building on the blooming Abkhaz coastline was handed over to Russia in yet another example of the Kremlin simply taking from its “brotherly” partner whatever it could grab — from the tiny village of Aibga to “Gorbachev's dacha” in Miuseri.

The ill will between the former imperial metropole and its former colonies also extends to unoccupied areas of Georgia. Last summer, the country experienced a wave of cruise tourism, as one after another, sea liners full of Russian passengers began to anchor in Batumi. Of course, sometimes a cruise is just a cruise, just as air travel is usually just a way of making one’s way around the world. In Georgia, however, these cruise ships were interpreted as a form of time travel — back to the imperial past — and they duly sparked protest. Many of the tourists themselves contributed to the tensions, making it clear that they were not just docking in Batumi as if it were an unambiguously foreign city. To them, Batumi was not a faraway foreign place like Marseille, or Dubai. Instead, many of the Russian passengers expressed the sentiment that they were returning to Georgia, sincerely believing that they would be met there by people with a shared historical memory and common values forged by decades of political union. Those Georgians less than enthusiastic about the Russians’ return were assumed — by the Russians at least — to be a minority.

Demonstrators protest the presence of a cruise ship carrying Russian passengers in the Georgian port of Batumi on July 27, 2023

Photo: Eka Lortkipandze / RFE/RL

Every imperial history has its own afterword, but whether the old metropole in question were London, Paris, Lisbon, or Moscow, they tend to bear certain similarities. The first stage typically involves attempts to minimize extreme reactions or reprisals. What comes after is investment in a new era of “special relations” — the exertion of “soft power” — and the operation is rarely cheap, even if it sometimes pays off in the end.

However, for those who want to save money, there is a cheaper option — “brotherhood.” Rather than recognizing historical realities, the preservation of “brotherhood” between the old imperial center and its former colonies attempts to replace life after death with something akin to business as usual.

The criteria of brotherhood are bizarre. Ethnic or confessional ties are of course frequently cited, but fraternity seems to have no clear rubric. For example, Moscow’s former Yugoslav “brothers” — Serbs and Montenegrins — do not substantially differ based on formal characteristics such as ethnicity or religion. A yet the Kremlin’s relationship with Belgrade appears much more familial than that with Podgorica.

Local cadres decide everything

In an empire, everything starts with co-opting — “buying off,” if one wishes to avoid the overuse of euphemism — the conquered elites. For imperial Russia, new territories were not so much an economic acquisition as a new outpost, and the process of expansion here was self-replicating. The initial idea of security required economic expansion, which in turn required securing the newly acquired economic assets, leading to another turn in the cycle of further expansion. The distinction between offensive and defensive doctrine was easily erased, hence the confusion in terminology. The term “outpost” took on a “brotherly” character — something Russia “encouraged” Armenians to be proud of.

The term “outpost” took on a “brotherly” character — something Russia “encouraged” Armenians to be proud of.

The forms of incentives for local leaders were not limited to material interests. Help in fighting political opponents, for example, is highly valued, and in this respect, the activities of the French administration in Africa were not all that different from the efforts of the first Soviet “big brothers” in Central Asia, or of their modern heirs in the North Caucasus.

The Armenian-Russian Cossack Union building in Yerevan

But the approach to another method of encouragement — career advancement — was fundamentally different. The traditional colonial style envisioned a mostly localized career, with migration to the metropolis seen as more of a “happy retirement.” This approach was determined both by the essence of colonization, which did not require mixing, and by the logistics of the matter, which objectively made such “mixing” difficult. The latter “brotherly” model, however, was spared from these difficulties, as it facilitated the internationalization of elites — as a form of buying loyalty, as a way to destroy dangerous potential coups, and as a mechanism for creating and strengthening loyal groups in the administrative center.

In the Soviet era, the promotion of national cadres to the very top was a rather exceptional event (Ukraine was such an exception): Latvia’s Boris Pugo, Azerbaijan’s Heydar Aliyev, and at a very late stage, Georgia’s Eduard Shevardnadze, all made it to senior positions in Moscow. However, the migration of the middle-level elite, not only bureaucratic, but also cultural, scientific, athletic, and high-level professionals, had perhaps an even greater effect. At the moment of disintegration in 1991, it turned out that many professionals from Ukraine had ended up in Moscow, and the failures of Ukraine’s first years of independence were often attributed to the resulting deficit of professional talent.

Heydar Aliyev and Eduard Shevarnadze

But what was more important was that these scientists, bureaucrats, athletes, artists, and engineers who had built their lives in the center of the empire suddenly found themselves trapped in a double loyalty. The myths of “eternal brotherhood” made it possible for many of them to escape from the contradictions that threatened to disrupt the comfortable lives they had built far from the lands of their birth.

One Armenian official spoke bitterly about his brother who had settled in Russia: “He knows that he will never become a full-fledged Russian. He will remain ‘black’ (he used a different word, of course), and his children will remain ‘black.’ But he has already established his life there. What should he do? He has already convinced himself that everything is not so bad, but he needs me, here in Yerevan, to think so too!”

Although my source did not give in to the following mode of thought, a considerable share of these “brothers” will, on occasion, parrot their “Russian” relatives: “Well, yes, and who should we support — Ukraine, maybe, or America?”

Family business

Personal motives of brotherhood turn out to be much more systematic and persistent than political preferences. They are better at self-reproducing, and almost naturally fold into the order of things. Protest and objection here is not a political position, but a violation of the system of values, and working with it — rather than against it — seems much more comfortable.

Russia’s relationship with Ukraine in this respect is a perfect example of these contradictions. On the one hand, Ukraine has a long and difficult history of struggle, including within itself, for the right to recognize its own identity. On the other hand, it has a no less dramatic history of participation in the strengthening of the empire, which converted the Ukrainian impulse to self-determination into the position of “second among equals.” From election to election, from protest to protest, from the west of the country to its center, the project of self-creation was viewed with suspicion, and not only by the powers that be in the old metropole. Dissidents who supported the Lithuanian Sąjūdis and perhaps even Georgia’s Zviad Gamsakhurdia were suspicious of the Ukrainian case.

Perhaps this is the real essence of the fashionable but misunderstood formula put forward by Ukrainian politician and writer Volodymyr Vynnychenko — “the Russian democrat ends where the Ukrainian question begins.” This isn’t about democracy, but about the very trap of “brotherhood,” which presents many with a false choice: what is clear about Lithuanians, Georgians, and all those who are considered “conquered” does not apply with the same unambiguity to those who are declared “brothers.”

What is clear about the conquered does not apply to those who are declared brothers

Imperial logic sees the protest of the conquered as a rebellion and the protest of “brothers” as a betrayal. It also applies, in a softer form, to those who do not regard themselves as defenders of the imperial idea at all.

The habit of perceiving Ukraine as “one of our own,” it would seem, should have worked against the decision to go to war. But it was precisely this perception that stimulated it

This is likely the source of the persistence with which the Russian authorities absolutize the idea of “brotherhood” vis-a-vis Ukraine. They see it as a complete, but criminally forgotten ethnic unity — and, accordingly, any attempt by Kyiv to break away from Moscow’s orbit is interpreted as an unthinkable betrayal. This, perhaps, is the key to understanding the main contradiction: the habit of perceiving Ukraine as “one of our own,” it would seem, should have worked against the decision to go to war. But it was precisely this perception that stimulated it.

Myths of brotherly nations

Even such a seemingly indestructible matter as “imperial brotherhood” has its own Achilles heel. The secret of its vulnerability lies in its secondary nature — and in its modus operandi. Brotherhood is good because it exists as the original order of things — or at least, it does right up until issues arise. At that moment of crisis, motives of kinship are immediately abandoned in favor of practical calculations.

Even such a seemingly indestructible matter as “imperial brotherhood” has its own Achilles heel

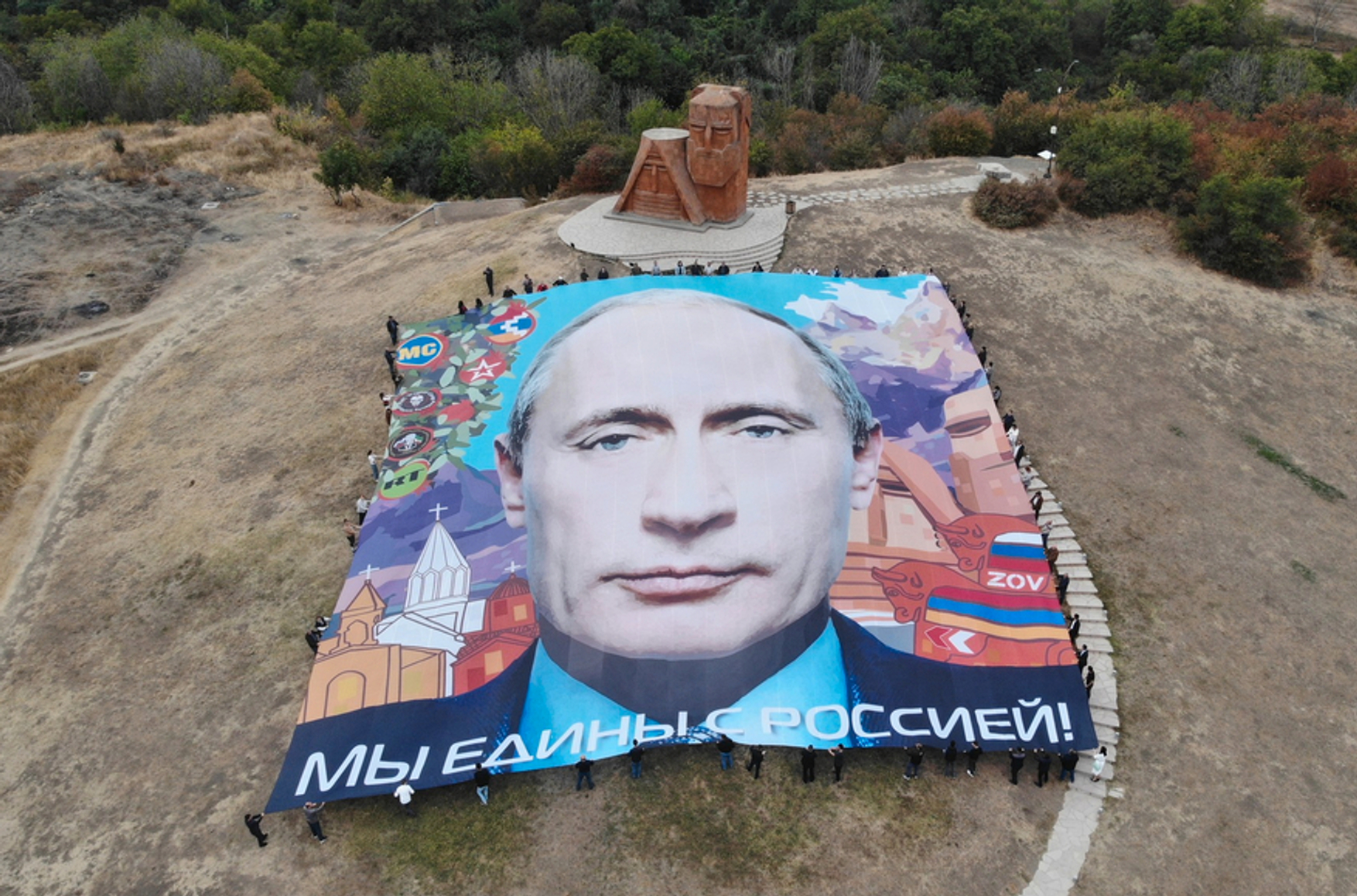

Russia’s “brotherhood” with Armenia has always existed in two planes. At the mundane level, all the parameters of identity in Armenia have been traced back either to history — the antiquity of which surpasses the boldest dates of Russian statehood — or to the motives of the tragedy of 1915: the Armenian genocide. The widespread understanding in Armenia — namely, that the massacre was largely a consequence of Russia's attempts to use Armenians in its conflicts with Turkey — easily coexists with the habit of considering Russia as a guarantor of security. Despite lessons from the not-too-distant past, Yerevan has largely convinced itself that similar cataclysms, whether perpetrated by Baku and Ankara, will not repeat themselves so long as Moscow remains interested in preventing them.

By and large, this was a sophisticated form of Stockholm syndrome — a harbinger of future trauma. Out of this contradiction, the Armenian authorities developed their own doctrine: no matter how much Armenia wants to go its own way, it cannot risk its security, which only Russia can provide, and therefore there are “red lines” beyond which no Armenian patriot can step. In this ingenious way, Armenian patriotism was equated with that of “Greater Russia.” The doctrine worked for everyone — perhaps most of all for the Armenian authorities themselves, who shifted the responsibility for what was happening in their country to Russia.

In short, the myth was convenient until the nourishing environment for its existence — the status quo in Karabakh — disintegrated. This tale of “brotherhood” was, of course, part of a multi-volume collection of myths and it is by no means the last one that will need to be addressed.

It was convenient to live in the myth until the nourishing environment surrounding it imploded

Of course, these “brotherhoods of convenience” are not unique to the Russia-Armenia case. For the Serbs, the main myth of identity, for which Moscow tries to create a “brotherly” Russian-Serbian bond, is actually Kosovo. Sometimes the secondary becomes so habitual that it is indistinguishable from the primary, but time and historical reversals eventually put everything in their place, albeit with some delay. The ancestral homeland is an ancestral homeland, but Europe is still closer than the tale of “Orthodox brotherhood.” By maintaining their “brotherly” ties with Russia, the Serbs risk nothing: unlike Ukraine, they are far away from Moscow, and at least for now, the relationship only seems to bring profit to Belgrade (in more senses than one).

But there is another flaw in the technology of “brotherhood,” perhaps a more systemic one. On the one hand, the resource is self-reproducing, as it does not require investment, only maintenance. On the other hand, this lack of immediate crisis lulls the family tyrant — the “big brother” — into a deceptive state of relaxation. He starts to think that everyone will stay in their place. That’s when vulnerabilities in the relationship start to emerge, sometimes with fratricidal consequences.

Regions that were treated in a “brotherly” fashion seem to lack long-term strategic importance — for Moscow, there is only the here and now. Like the government house in Pitsunda. The whole value of the centuries-old “brotherhood” with Armenia is now monetized into control over the road from mainland Azerbaijan to Nakhichevan and further into Turkey. The temptation of leaving strategic expectations for today's cash is reinforced by the belief that every country will have its vulnerabilities that Russia can exploit. Which is precisely what Peskov was referring to.