On June 5, a NATO naval exercise was launched off the Swedish coast on a scale unprecedented for the Stockholm archipelago as the Alliance expressed its solidarity with Sweden’s and Finland’s decision to join the organization. This decision was difficult for Sweden, because its neutrality was considered an important part of the country’s success story. The attack on Ukraine was the turning point, and public sentiment, and consequently the rhetoric of political parties, changed dramatically. Joining the Alliance would not only strengthen Sweden’s security, it would also strengthen NATO’s capabilities: Sweden’s army is small, but it meets all modern standards. Russia is not threatened by this enlargement, but if Putin wants to attack the Baltic states, it will be harder to do so now.

Content

Non-aligned for 200 years

NATO’s informal ally

Open Partnership for Peace

Finland’s Concerns

How the parties resisted

Joining NATO is safer and cheaper

Ready for defense against Russia

Non-aligned for 200 years

“We were in favor of NATO membership back when this tie was in fashion,” reads a campaign poster featuring Swedish Liberal Party leader Johan Persson, photographed wearing a garishly colored tie. That’s right - the party has had a NATO membership on its program since 1999. But at the time, membership in a military bloc seemed an extremely dim prospect. Other parties of the center-right alliance gradually joined the Liberals: the Moderate Party, the Christian Democrats and the Center Party. But the Left - the Social Democrats, the Left Party, and the Greens - continued to oppose it. The national-populist Swedish Democrats, although considered right-wing, were also against joining the alliance. As befits a party with a strong nationalist bent, they had always been against participation in the EU or any international integration at all.

Given such a state of affairs, the talk of joining NATO could have gone on for years. Firstly, because the Swedish Democrats control only about 17 percent of the votes in the Riksdag, a position that deprived the right wing of a parliamentary majority on this issue. Secondly, it would have been politically impossible for just one bloc to make such a decision - at least not without a referendum. That would be too great a shift in defense policy, in mass consciousness, and in how Swedes see their country.

Until now, the concept of Swedish defense policy has been described by the formula “non-alignment in peacetime, neutrality in wartime.” This concept is about 200 years old and has helped the country stay out of the wars that have shaken the continent. During that time, Sweden has earned a reputation as one of the most peaceful countries in Europe - a serious achievement for a country that spent the 17th and 18th centuries in ceaseless wars and created a regional empire in the north of the continent.

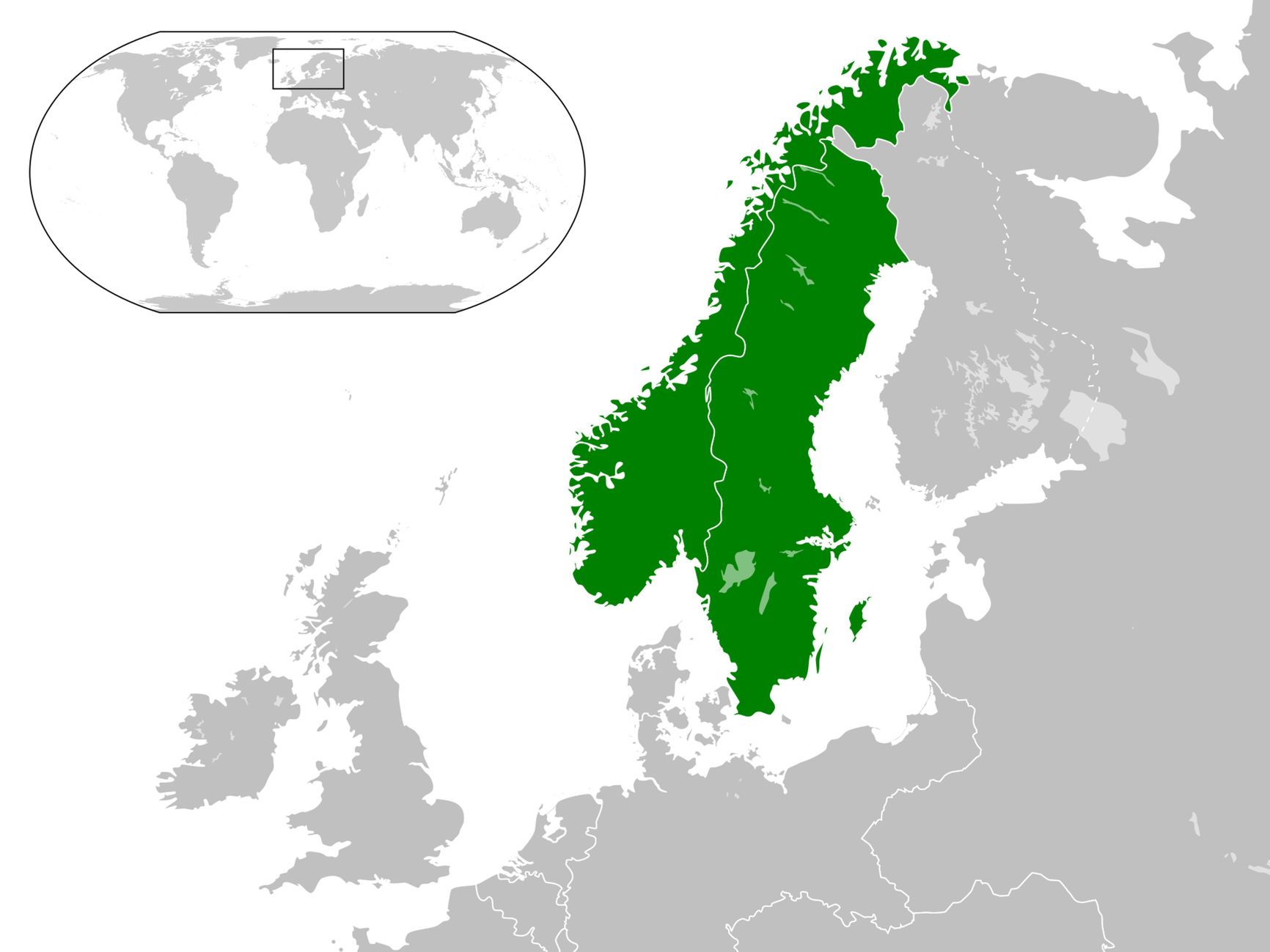

It is true that by the beginning of the nineteenth century not a trace of the former glory and overseas territories had remained. After the loss of Finland in 1809, Sweden’s territory shrank to the geographical area of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The urge for new wars of conquest had long since disappeared, and the economy was in deep decline. But the geographical position with seas on almost all sides ensured reliable protection of its territory.

Map of Sweden and Norway in 1814-1905

King Johan XIV, who ascended the throne in 1818, proclaimed that Sweden’s main policy was to avoid new wars and not to participate in military alliances. After more than 200 years of peace, it is clear the plan worked. However, “Swedish neutrality” itself was quite flexible and allowed for pragmatic compromises. Without ever going to war, Sweden was involved in various international military operations, for example, in Liberia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Libya, and Afghanistan.

In 1939, when the Soviet army invaded Finland, Sweden changed its status from “neutral” to “not participating in hostilities.” This made it possible to offer the neighboring country massive support in terms of arms and ammunition. In addition, thousands of Swedish volunteers, many of whom were “vacationers” - regular military personnel who had taken leave of absence for the duration of hostilities with the consent of their superiors - fought on Finland’s side.

During World War II, Sweden, surrounded on all sides by occupied territories or German allies, struggled to maneuver between the two sides. For Germany, Sweden was a major supplier of iron ore (it was thought that refusal to export would lead to the occupation of the country) and allowed transit of German troops to Norway. At the same time the country supplied ball bearings and anti-aircraft guns to Great Britain, and from 1943 it increasingly supported the actions of the anti-Hitler coalition. For example, Sweden hosted navigational stations for controlling American and British bombers, opened its airspace for the Allies, and effectively served as a base for the Norwegian Resistance.

During World War II, Sweden struggled to maneuver between the two sides

In the postwar period, neutrality was largely determined by the fact that Sweden was one of the most politically left-wing countries in Europe. From 1936 to 1976, the country was ruled by the Social Democratic Party, which contributed to Sweden’s image as a bridge between the East and the West. Sweden was open to dialogue with both sides, but at the same time could afford harsh criticism of both. It condemned the communist regime in Czechoslovakia after the suppression of the Prague Spring - and yet its prime minister, Olof Palme, was one of the most ardent and consistent critics of the American war in Vietnam. That annoyed the U.S. authorities, who were well aware of the hidden side of “Swedish neutrality”: the country was in fact an informal NATO ally and counted on American military assistance in the event of a Soviet invasion.

NATO’s informal ally

Sweden’s history of close cooperation with NATO is almost as long as the history of the North Atlantic Alliance itself. After the end of World War II, the threat of invasion could only come from the Soviet Union and its satellites. It was unrealistic to face it alone - and the country needed access to modern military technology possessed by the U.S. and its allies.

In 1946, the Swedish government was headed by Tage Erlander, a staunch anti-communist and a great friend of the United States. The situation was tense: the Soviet Union was establishing communist regimes in Eastern Europe, and in April 1948 Finland was forced to sign a “Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance” with the USSR. It essentially deprived the country of full sovereignty and placed it in a dependent position. Norway was thought to be next in line. “All indications are that the Soviet advance in Scandinavia will continue,” the worried prime minister wrote in his diary in March 1948.

A prototype of NATO, the Brussels Pact between Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, was created at the same time. The allies immediately launched negotiations with the U.S. to establish a defensive alliance. A year later, the North Atlantic Treaty was signed, with one of its articles requiring all its members to defend any member of the organization form outside attacks. Initially, there were 12 countries in the organization, including Sweden’s closest neighbors Denmark and Norway. By the mid 50’s the organization had expanded to 15 countries - Greece, Turkey and West Germany had joined the bloc. Neutral Sweden remained on the sidelines, but it was mostly a fiction – well-informed people within the organization called Sweden the “sixteenth member.”

Neutral Sweden was referred to as “the sixteenth member” by well-informed people within NATO

First, Sweden joined the embargo on supply of military products to the Eastern Bloc in order to gain access to U.S. military technology and buy NATO weapons. That, of course, was inconsistent with the principle of “neutrality,” so the embargo was kept under wraps. Secondly, Sweden entered into a secret agreement with the United States in 1952 that guaranteed American military protection in the event of an attack. In addition, the country pledged to give the alliance access to its airspace and military infrastructure if necessary. In 1957, NATO adopted a doctrine to defend Scandinavia as one territory.

Finally, Sweden actively exchanged intelligence with the U.S., particularly by leaking information on North Vietnam, a country involved in the war that the Swedish government so strongly condemned. But the Swedish intelligence services’ main efforts were aimed at gathering information about their eastern neighbor, the Soviet Union, primarily by means of radio-electronic reconnaissance. For this purpose, the Pentagon provided Sweden with the necessary equipment, receiving Swedish intelligence in return.

The cooperation was kept in strict secrecy for decades - not even all members of the government were privy to it. Swedish diplomats and politicians were instructed to avoid any public contacts with NATO structures and never to visit the alliance headquarters in Brussels.

Open Partnership for Peace

Since the mid-1990s, close cooperation between Sweden and NATO came out of the shadows and was formalized as part of the Partnership for Peace program. Joint military exercises, coordination of actions, regular visits of NATO warships to Swedish ports – all normal partnership relations that suited both sides. In 1997 Joran Persson became the first head of the Swedish government to attend a NATO summit. The Swedish ambassador to the Alliance was appointed the same year.

Yet, interest in full-fledged NATO membership was nevertheless rather tepid - only 21% of Swedes supported joining NATO in 2001. The likelihood of a new full-scale war in Europe seemed close to zero, so it was unclear against whom the country should defend itself. European armed forces at the time were not preparing to defend their territories but rather to participate in international peacekeeping operations.

A shift in public opinion and politicians’ attitudes toward national defense began in 2014, after the annexation of Crimea and the armed conflict in Donbass. In Europe, the consensus was that the threat of new wars was becoming increasingly real, so NATO’s defense capabilities should be focused again on protecting its territory from invasion.

A shift in public opinion began in Sweden after the annexation of Crimea

For Sweden, this meant preparing for new challenges and increasing its ability to defend itself - although the risk of a direct Russian invasion of Sweden was still seen as extremely low. But it seemed highly likely that Sweden would get involved in an armed conflict if Russia tried to “bring the Baltic states back home,” as Russian propagandists had enthusiastically discussed.

The first thing Sweden did in 2015 was to re-establish a military garrison on the island of Gotland, a key to controlling the Baltic because of its strategic position. The reinforcement of the island’s garrison proceeded step by step. The most important one occurred in January 2022, when about 100 vehicles and personnel were redeployed to Gotland.

The country’s defense budget rose from 1% to 1.7% of GDP between 2017 and 2021, and in March 2022 the government decided to raise it to 2% of GDP (the NATO standard) as quickly as practicable.

Swedish and Finnish cooperation with the North Atlantic Alliance moved to a new level in 2016 when the two countries were elevated to Enhanced Opportunity Partner status. Integration at the level of military leadership and combat training of the armed forces increased significantly at that point in time. There was also a swing in public opinion: by the mid-2010s, 40 to 45% of Swedes had already been in favor of NATO membership. At the political level, however, the political blocs were still divided over NATO membership: rightists were for it, leftists and nationalists were against it. Therefore, the prospect of the country’s membership in the military bloc still seemed quite remote.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 made Sweden’s accession to NATO almost inevitable. Already in March, polls showed that a majority of the population - about 53% - was ready to support it. And Finland played a significant role in the Swedish pro-NATO discourse.

Finland’s Concerns

For Finland, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seemed very similar to the Winter War, which defined the country’s entire postwar defense policy. That the USSR and then Russia might want to “repeat it” was always a very realistic scenario for the Finns. Unlike most European countries, Finland built and trained its armed forces so that they would be capable of effectively repelling a full-scale invasion by a large regular army.

That Russia might want to “repeat it” was always a very realistic scenario for the Finns

The Finnish army, although relatively small (21,000 soldiers in peacetime), has an active reserve. In the event of a war, it will be helpful in quickly increasing the size of the Armed Forces to 240,000 and in the longer term to 900,000. In addition, Finland has the strongest artillery in Western Europe, and that, as the war in Ukraine has shown, may be the key to a successful defense. Besides, unlike Sweden, Finland has maintained a system of mobilization depots with various strategic reserves - from winter underwear to fuel and lubricants in case of a war.

By heroically resisting Soviet aggression during the Winter War, the Finns earned themselves a serious military reputation in the Nordic countries that has remained to this day. Many in Sweden have joked that when it comes to joining NATO, one should “consult the grown-ups”, that is, the Finns.

After the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, support for joining NATO in Finland jumped from 20 percent to 60 percent. All major political forces in the country - including the ruling Social Democrats - supported accession. The fact that the matter was almost decided became clear as early as April. For the Swedes, it was a serious argument - polls showed that if Finland joined NATO, about 63 percent of the population would be in favor of Sweden joining the bloc.

In addition, the analogy with the Winter War worked well in Sweden. As early as the second week of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Swedish government promised military aid to the Ukrainian side – it was the first time since 1939 that the country sent weapons to a war zone. Memes in support of Ukraine, remade from old posters in support of Finland, appeared on Swedish social media as journalists reported on hundreds of volunteers joining the Ukrainian International Legion.

How the parties resisted

Such a strong shift in public opinion could not be ignored by politicians. New elections have been scheduled for the Riksdag in September, but the leading political parties clearly did not want to include this issue into the pre-election struggle: it would overshadow all other topics for discussion. Especially the ruling Social Democrats, who have always been against joining NATO: in the current political and military situation it would work against them.

The Swedish Democrats were the first to break. And it’s no surprise: despite the party’s official anti-NATO and anti-EU stance about 70 percent of their voters were in favor of joining the North Atlantic Alliance. On April 11, an emergency meeting of the party leadership decided to support NATO membership if Finland decides to join too. That would have been enough for a parliamentary majority, but such an important decision required a broad consensus of right- and left-leaning political forces.

It was useless to talk to the extreme left on this topic: they consistently opposed not only joining NATO, but even cooperating with the bloc. The Greens took a similarly tough anti-NATO stance. But those two parties controlled a total of only about 12% of the Riksdag, so they could be ignored. In order to make the accession to the North Atlantic Alliance a reality, the support of the Social Democrats, the country’s largest party whose electorate was roughly equally divided on this matter, was required.

Little was required of the Social Democrats: they simply needed to do an about face in their attitude. On February 24, at an emergency government meeting devoted to the outbreak of war in Ukraine, Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson firmly stated that Sweden’s accession to NATO was not under consideration and that Sweden would retain its non-aligned status. She reiterated the same position in early March.

Little was required of the Social Democrats: they simply needed to do an about face in their attitude

But as early as the beginning of April, information began to leak into the press that the government was ready to make a drastic U-turn on the matter. Active consultations with Finland in the field of security policy were launched to the accompaniment of joint press statements by the prime ministers of the two countries. Their point was that the countries would confer and decide together what would be best for their mutual security.

The rhetoric of politicians also started to change. The question of NATO membership in the public discourse began to gradually shift from purely pragmatic security considerations to points of moral choice. “One cannot remain neutral between a forest fire and a fire department,” as the dilemma was formulated by the liberal leader Johan Persson. Under those circumstances, NATO was no longer just a military alliance but a solid club of democracies, a reliable guardian of freedom and democracy.

Joining NATO is safer and cheaper

On April 20, in an interview to Swedish TV, Magdalena Andersson openly admitted that NATO membership was not out of the question, but that the final decision would be made based on in-depth analysis. On the same day, Aftonbladet, the main mouthpiece of the Social Democrats and the Swedish Left in general, published an article with the headline “Putin’s War Shows We Need to Join NATO.” This was about as abrupt a turnaround for Swedish politics as if Rossiyskaya Gazeta had published an article calling for LGBT rallies in Moscow.

The in-depth analysis of security policy that Magdalena Andersson had spoken of was carried out by a special government commission. It included representatives from all parliamentary parties. On May 13, the commission made its findings public:

• Sweden’s membership in NATO would increase the likelihood of a possible armed conflict in which the country might be involved.

• NATO membership will contribute to the country’s security and help Sweden contribute to the security of its close neighbors.

• If Finland joins NATO and Sweden remains outside the bloc, the country will find itself in a particularly vulnerable position.

Six of the eight parties represented in the Riksdag supported the analysis. The matter was decided, among other things, for purely pragmatic reasons. According to Swedish Defense Minister Peter Hultqvist, the alternative scenario – which involved remaining outside NATO and increasing the country’s defense capabilities - would have required a huge outlay of 3-4 percent of GDP, which would have been too much of a burden on the Swedish economy. It would be safer and cheaper to defend the country together with NATO.

On the morning of May 18, the Swedish and Finnish ambassadors to NATO submitted official applications for membership in the North Atlantic Alliance on behalf of the two countries to the organization’s headquarters.

Finnish and Swedish Ambassadors to NATO submit applications for NATO membership to Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg

Ready for defense against Russia

The main bonus for Sweden will be a guarantee of protection under Article 5 of the NATO charter: an attack on one of the countries within the defense alliance is considered an attack on the entire bloc, and in such a case Sweden will not be left alone. True, accession to the alliance will require further deepening of military integration with the bloc, and the Swedish military command will become part of the NATO command and control system. But it won’t be problematic: Sweden has been conducting joint exercises with NATO for more than two decades, has participated in many peacekeeping operations with the bloc, and many Swedish and NATO officers have long been well acquainted with each other.

As for the Alliance, the addition of two new members will be a huge gain for it both militarily and geostrategically, as well as a significant strengthening of the bloc’s northern flank.

For NATO, the addition of two new members will be a huge gain both militarily and geostrategically

The Swedish army, though not very large (23,000 persons in service and 31,000 in reserve), is equipped to modern standards and very well trained. Since the middle of the last century, the Swedish armed forces have been managed under the mission command doctrine, which foregoes strict centralized command and blind compliance with orders. It is focused on achieving combat objectives by whatever means are available, leaving a wide margin for initiative for commanders at all levels and for individual soldiers. This type of military culture requires a high level of tactical training and is very well suited to the concept of “network-centric warfare,” which has been actively implemented in NATO countries.

But Sweden’s biggest contribution to the North Atlantic bloc’s overall defense infrastructure will be its air force and navy - disproportionately large for a country with such a small population. The Swedish air force has more than two hundred planes and helicopters, including more than 90 Jas 39 Gripen fighters, the Swedish company SAAB’s own production. Some experts call them the best fighters in the world without stealth technology.

These aircraft have one extremely valuable feature that would help Sweden keep its air force safe in the event of a conflict with Russia: they don’t require airfields. The Jas 39 Gripen can use ordinary highways as a runway and can be serviced, refueled and armed using mobile stations and a secret network of “roadside air bases”. Many Swedish roads are specifically designed to be used by planes.

If we remember how the invasion of Ukraine began with Russian missile and air strikes on airfields, the ability to disperse and hide their aircraft could help greatly in preventing their loss during the first hours of the war. In addition, the Jas 39 was specifically designed as a Sukhoi killer, although there were no opportunities to test its capabilities in combat against Russian aircraft.

Sweden’s largest contribution to NATO’s overall defense infrastructure will be its air force and navy

The Swedish fleet includes, among other vessels, seven corvettes and five submarines. By comparison, the Russian Baltic Fleet has only a single Soviet-era submarine.

The Visby

If we add Finland’s naval and air forces, then, once the two countries have joined NATO, the Baltic will finally become a “NATO inland sea” and the Swedish island of Gotland, an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” in the middle of this sea. The Baltic states which Sweden and Finland would be able to protect from sea would benefit the most from this development (and the whole of NATO would benefit as well from the use of their airspace), This will make any plans to retake the three Baltic states by force extremely difficult to implement. Sweden’s and Finland’s application to join NATO was greeted with particular enthusiasm in Tallinn, Vilnius and Riga for a reason.

As for Russia, there is no danger for it in this NATO enlargement. And not only because it is difficult to imagine a situation where Sweden and Finland would want to participate in an attack on Russia, but also because both countries have declared their unwillingness to allow deployment of permanent NATO units, much less nuclear weapons, on their territory. Thus, all the talk of flying time to Moscow from Helsinki and Stockholm makes no sense. Not to mention that the Baltic states have been members of NATO for two decades.