In Turkey's spring elections, the dictator Erdogan will run against Kemal Kilicdaroglu, a single candidate from the National Alliance of six parties, with polls showing him ahead of Erdogan by 10 points. Like Putin, Erdogan is trying to distract the nation from domestic troubles with foreign policy, but this trick is quickly getting old. Even though Erdogan's Turkey has been stripped of many democratic rights and freedoms, national elections remain competitive. Kilicdaroglu’s victory would dampen the relations between Moscow and Ankara, but Turkey's overall foreign policy would still sustain fewer drastic changes than the domestic landscape.

Content

A quest for a perfect rival

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, “Turkey's Gandhi”

A Kemalist against a neo-Ottoman believer

Erdogan won't go out without a fight

Reputation shaken by the earthquake

Turkey – Ukraine – Russia

Turkish-Russian projects post-election

A quest for a perfect rival

The National Alliance, which consolidated six political parties, spent several months actively debating which candidate could put an end to the twenty-year rule of Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AK Party). Early in March, the opposition bloc was on the brink of collapse. One of the participants of the Table of Six political conference, the leader of the Good Party Meral Aksener, voted against the candidate who enjoyed other participants’ support: Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the head of the Republican People's Party. Aksener insisted that his more popular fellow party members, Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu or governor of Ankara Mansur Yavas, would be a better choice. However, other conference participants thought that nominating mayors was too risky: in the event of defeat, they would lose their respective offices, depriving the opposition of control over the largest cities.

On March 3, Aksener announced her withdrawal from the coalition, thus shattering opposition supporters’ hopes of victory. “The opposition platform ceased to reflect the people’s will,” the head of the Good Party stated. However, as early as on March 6, the opposition members found common ground. Aksener consented to nominate Kemal Kilicdaroglu on the condition that the leaders of five remaining opposition parties get vice presidency if he wins.

The Turkish opposition includes six parties: the Good Party (Iyi Parti) – conservative nationalists, the Felicity Party (SAADET) – Islamists, the Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA) and the Future Party (Gelecek) – two parties formerly allied with Erdogan, the Democrat Party – liberal conservatives, and the country's main opposition party, the Republican People's Party (CHP), once founded by Ataturk. Despite their serious controversy on many issues, the drive to depose Erdogan and restore the parliamentary republic has been enough of an incentive for the opposition to look for common ground, explains Ruslan Suleymanov, an expert in Oriental and Turkic studies and political scientist.

The last time the opposition joined forces was to topple Erdogan's allies in the 2019 municipal elections. Back then, the Alliance restored control over Turkey’s two principal cities, placing Mansur Yavas and Ekrem Imamoglu in charge of Ankara and Istanbul, respectively. Those elections challenged the invincibility of Erdogan and his party.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, “Turkey's Gandhi”

Erdogan's main adversary is 74 years old. Kemal Kilicdaroglu has been at the helm of the Republican People's Party since 2010, and his nomination was supported by an unprecedented 1246 out of 1250 delegates. For his level-headed manner of speaking and visual likeness, he has been nicknamed “Turkey’s Gandhi”. He might as well have been dubbed “Turkey's Navalny”, for his anti-corruption investigations. In 2008, two of Erdogan's deputies in the AKP, Saban Disli and Dengir Mir Mehmet Firat, stepped down after debates with Kilicdaroglu, who accused them of corruption. Now Kemal Kilicdaroglu looks to depose Erdogan. “Today, we are very close to overthrowing the tyrant's throne,” the CHP leader declared early in March.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu

Kemal Kilicdaroglu accuses Erdogan of political persecution and “witch hunts”. In 2017, Kilicdaroglu organized the March for Justice to support almost 500,000 detainees all over the country. The procession from Ankara to Istanbul gathered around 2 million people. The formal pretext for the rally was the politically motivated sentence passed to journalist and deputy Enis Berberglu, who’d been sentenced to 25 years in jail for releasing the video of Turkish security services transferring weapons to Syrian insurgents. The video disproved Erdogan’s claims of Ankara’s non-involvement in the Syrian conflict.

The March for Justice organized by Kilicdaroglu in 2017

DW

“Kilicdaroglu cannot be called a ‘cosmetic’ candidate in any case,” remarks political scientist Ruslan Suleymanov. “Of course, his support rate is lower than that of younger, more popular mayors of Istanbul and Ankara, but he still has all the chances to defeat Erdogan as someone who can consolidate the protesting voters.”

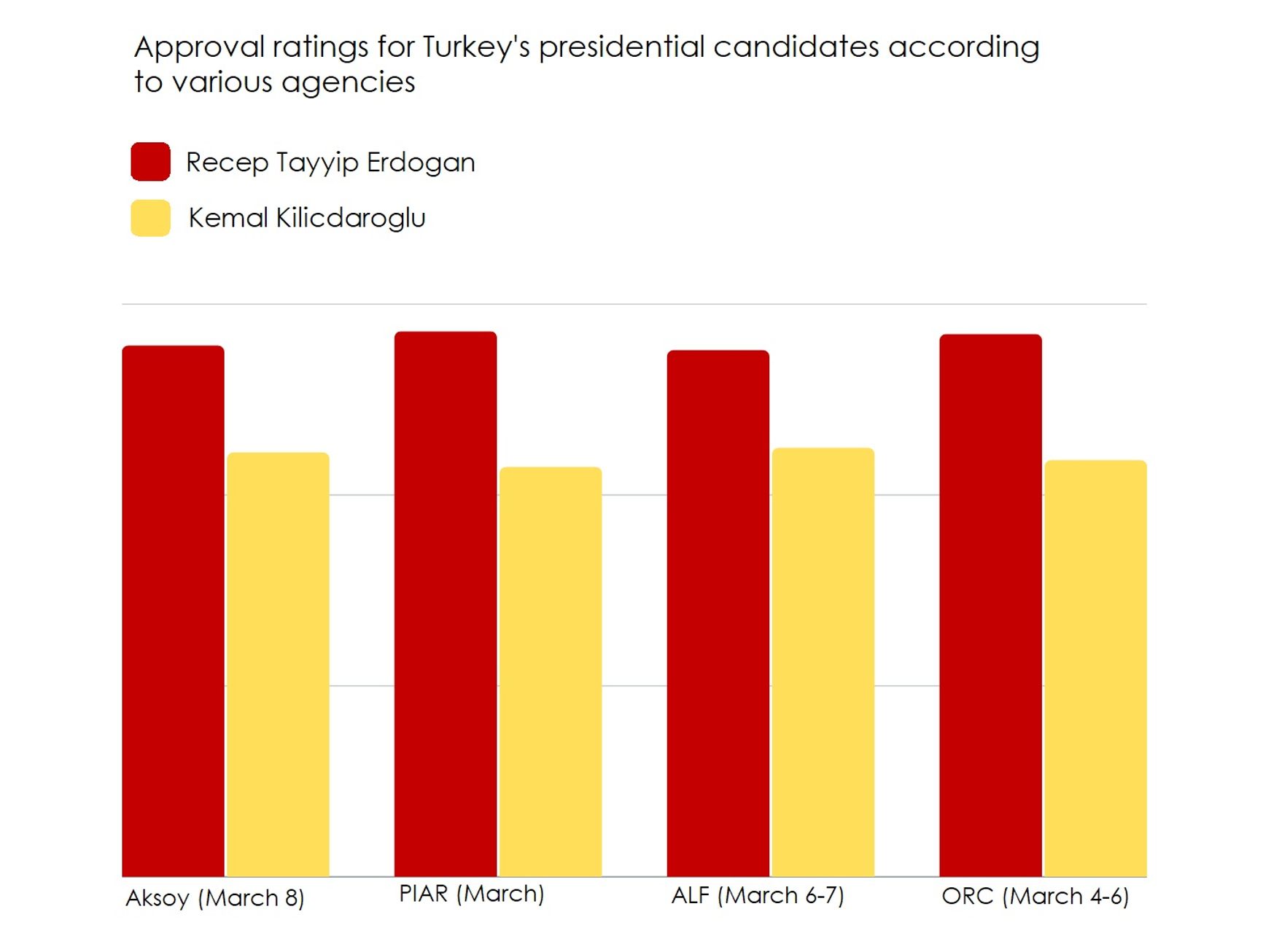

According to the latest survey, Kilicdaroglu is backed by 56,8% of respondents, while Erdogan won 43,2% of votes. Other studies show similar results. However, the CHP leader may need the backing of the third strongest parliamentary faction to win the election: the People's Democratic Party (HDP), which secured almost 12% of votes in the previous election and holds 67 seats in the parliament but stays away from the opposition bloc. The party defends the rights of ethnic minorities and is popular with the Kurds, whose votes will be decisive in the upcoming election, explains Aurélien Denizeau, an independent researcher specializing in Turkey. “About a third of the Kurdish population traditionally votes for Recep Tayyip Erdogan as conservative Sunnis,” Denizeau says. «The vote of the remaining two-thirds, which usually vote for the HDP, is less certain.”

The Kurds could become the kingmakers in the upcoming elections

HDP co-chair Pervin Buldan has announced that the party will not nominate its candidate in the presidential election. Therefore, the opposition stands a chance to win some of the Kurdish votes. Meanwhile, Kilicdaroglu called for the release of a Kurdish leader, Selahattin Demirtas, who has been imprisoned since 2016 on the charges of involvement with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. In turn, Demirtas has spoken in favor of Kiricdaroglu.

A Kemalist against a neo-Ottoman believer

If Kemal Kilicdaroglu wins, Turkey could return to the foundations of its statehood that were defined by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the revered father of the Turkish nation. Kilicdaroglu has pulled his main electoral ace from his sleeve: the promise to deliver Turkey from authoritarian rule. “We, the leaders of the political parties forming the National Alliance, have coordinated a roadmap for a transition to a reinforced parliamentary system,” the head of the CHP announced.

Kilicdaroglu's party is convinced that Erdogan's Turkey has strayed away from the ideas of Kemalism (the ideology of national modernization proposed by Ataturk). The doctrine lies on six pillars, or “arrows”. The first pillar is the state as a republic with a government that is elected by the people and is accountable to them, unlike the absolute monarchy of the Ottoman Empire. The second pillar is nationalism, but Ataturk understood this concept as a unity of citizens within the boundaries of the Turkish Republic, and not ethnic or religious principles of consolidating all Turks, including those abroad. Other pillars include the secular state and its separation from Islam, a policy of combating the vestiges of traditional society, and a focus on progress and enlightenment.

Meanwhile, Erdogan came into power, driven by ideas of resurrecting Ottoman culture and traditions in modern Turkey. His party even came close to being banned in 2002 and 2008 for neglecting the principle of separation between the state and religion. Today, Kemalists have every reason to fear that Erdogan's victory would harbor further decay of democratic institutes. Thus, in 2017, the AK Party authorized Erdogan to amend the Constitution, thus reinforcing his presidential power and changing the system of governance from a parliamentary to a presidential republic. As the Venetian Commission established, Turkey no longer has the division of powers or a system of checks and balances in place.

“Many of Kilicdaroglu’s supporters view the AK Party’s policies and their flirtation with traditional values as a return to the Middle Ages and an attempt to establish the primacy of Shariah,” explains Ceylan Ozgul, political scientist and Middle East expert.

Erdogan won't go out without a fight

The Turkish president's rating during his latest term has been a rollercoaster ride, hitting an all-time low in December 2022, when only 38,6% of the respondents were willing to support him. “Numerous surveys show that up to 60% of the Turks are most certainly opposed to Erdogan's candidature today,” says Ruslan Suleymanov. According to him, the Turkish president won't go out without a fight, using every trick in his arsenal, from imposing martial law to engaging his vast administrative resources in the elections.

Still, falsifying the outcome of the popular vote would be tricky, insists Ozgur Unsuluhisarcikli head of the German Marshall Fund's Ankara office:

“Turkish elections are unfair, but they are real and competitive and the opposition has a real chance of winning.”

The Turkish president retains a loyal base and a profound influence on mass media and public institutions. Some of the swing voters will support him, says the expert. He believes Erdogan will play on voters’ fear and uncertainty: “He will say, ‘If you vote for me, you know who will govern the country. If you vote for them, you don't know what will happen.’”

Erdogan will play on voters’ fear and uncertainty

Like Vladimir Putin, Erdogan loves history and anniversaries. The election was scheduled for June, but the president moved them to the milestone date of May 14. On that day in 1950, Ataturk’s supporters lost the election to Islamists from the Democratic Party for the first time since the foundation of the Turkish Republic. Now, 70 years later, Erdogan looks to defeat Kemalists from the CHP on the exact same date. “Another symbolic coincidence is the upcoming 100th anniversary of the Turkish Republic on October 29, 2023,” remarks Ruslan Suleymanov. “Erdogan will do all in his power to mark this anniversary at the helm of the nation.”

However, he is approaching the election without much to show in the domestic arena. In 2022, the year-on-year inflation rate exceeded 64%, after reaching 85% in 2021, which was a record high since 1998. The opposition is convinced that the president and his entourage's short-sighted policy is to blame. Erdogan pushed for decreasing the interest rate despite economists’ advice to reign in rampant price growth by upping it. He appointed loyal officials as heads of the Central Bank and fired those who showed independence in their policies.

Reputation shaken by the earthquake

Killing over 60,000 people and destroying the homes of over 2.7 million, the severe earthquake that recently hit Turkey was also a heavy blow to the president's reputation. Incidentally, Erdogan came to power on the wave of the nation's frustration with the government that failed to manage the fallout of the 1999 earthquake and the economic crisis that followed in 2001.

Kilicdaroglu is racing Erdogan to visit as many affected regions as possible. Erdogan is posing as the savior of the nation, calling on people to consolidate in the face of the common grief, remarks Ruslan Suleymanov. But his trademark social-policy-oriented rhetoric (pay compensations, increase salaries, and build new houses) lacks the reassuring potential. The opposition has been quick to notice that it was the mistakes made by Erdogan's party that resulted in the blood-curdling death toll, says Suleymanov.

“Kilicdaroglu and his team are reminding Erdogan that his AK Party has announced a nationwide ‘construction amnesty’ eight times, offering the opportunity to pay a tariff for illegal construction. Furthermore, over half of the buildings in the ten most affected provinces were built after 2001, that is, during the AKP’s rule.”

Turkey – Ukraine – Russia

Erdogan seeks to compensate for his lackluster domestic performance with foreign policy advancements, primarily, Turkey's bigger international weight against the backdrop of the energy crisis ad the war in Ukraine. Leveraging the country's position in the aftermath of Russia and the West severing their mutual ties, he made Turkey an irreplaceable link in the processes integral to global security.

In July, Turkey contributed to the grain deal that ensured Ukraine's agricultural exports. In November, the deal was renewed – again, with Ankara at the table. Turkey-made Bayraktar drones played a prominent role in the early months of combat, showing the entire world that the Ukrainian military was fending off Russia’s offensive with a Turkish weapon. After the Nord Stream explosions, Russian authorities turned to Turkey as a possible location for a natural gas hub. Ankara is yet to join the anti-Moscow sanctions. However, it is also yet to recognize the occupied territories of Ukraine as Russian lands.

“If the opposition wins and does not make a political U-turn in contradiction to Erdogan's line, I believe Ankara will continue to work on remaining the key intermediary between Moscow and Kyiv,” argues Suleymanov.

Daily Sabah

The opposition's victory is unlikely to change Turkey's relations with Kyiv because Ukraine's territorial integrity is unassailable for the entire Turkish political class, believes Suleymanov. Since 2014, Ankara has been consistent in its condemnation of Crimea's annexation, and since February 24, 2022, of Russia's full-scale military invasion of Ukraine.

Kilicdaroglu's victory will most likely put a dent in Ankara's relations with Moscow but will strengthen ties with the EU. “We're unlikely to see the chemistry we observed between Putin and Erdogan,” says Suleymanov. The expert is convinced that the opposition is far from focusing on relations with Russia:

“We don’t have any specifics on Kilicdaroglu's position on Russia. Like the entire opposition alliance, the CHP leader pays extremely little attention to relations with Moscow. Similarly, the Kremlin banks on Erdogan and shows zero interest in the Turkish opposition.”

That said, even Erdogan's victory may turn out detrimental to the country's relations with Russia. The president may need funds to cover the immense damage caused by the earthquake. The UN estimated the amount to be over $100 billion, so Erdogan may need to turn to the West, considering that Russia has plunged into a crisis of its own.

Turkish-Russian projects post-election

The opposition and the AKP differ in their stance on joint projects and formats of cooperation with Russia. However, we shouldn’t expect them to be put on hold, warns Ruslan Suleymanov. Yet the terms could be reviewed in Ankara’s favor, which could be the case with the Akkuyu NPP construction. “We have become dependent on Russia for energy,” said Kilicdaroglu in August. “If you become dependent on energy policy, it will not be possible for you to follow an independent economic policy.”

According to the CHP leader, Erdogan is using Akkuyu to enrich his associates’ companies and as a political asset. Kilicdaroglu believes that the president is misleading the nation, presenting a project that is unprofitable and fraught with risks for sovereignty as beneficial. Under the contract, Turkey will have to purchase power generated by the NPP at a high rate of $12.35 per kilowatt hour up until 2040.

Erdogan is using Akkuyu to enrich his associates’ companies and as a political asset

The opposition is equally unhappy with Rosatom’s reluctance to share nuclear technology. According to Kilicdaroglu, certain NPP sections don’t hire Turkish engineers, technicians, or workers. It was Erdogan's party that rejected the opposition's proposal to include a clause on nuclear technology transfer into the agreement with Russia.

Another issue of critical importance for Russia is the construction of a natural gas hub in Turkey. For Moscow, it’s an opportunity to export its energy carriers all over the world, circumventing the sanctions. Procured by Ankara and mixed with Azerbaijani gas, for instance, Russian gas stops being Russian from the legal standpoint. This way, Gazprom could avoid a drastic decrease in extraction and profits. Nevertheless, Ankara has no plans of investing in the hub and offered Russia to cover the costs in full, like at Akkuyu. “If Russia has the money, it is most welcome to start the construction of the hub. It all comes down to investment,” said Cagri Erhan, a member of the Turkish Presidency's Security and Foreign Policies Council.

Neftegaz.ru

For Kilicdaroglu, the gas hub could become a strong card in the negotiations with Russia on Syria, believes Turkish political scientist Ceylan Ozgul. “If Kilicdaroglu wins the election, which is highly likely, he will have to send Syrian refugees back home as the only way for Turkey to improve its economic situation,” explains Ozgul. “That would require reaching an agreement with Putin on Syria. The construction of the hub could create an ‘alternative economy’ for Syrians in Syria, to the benefit of everyone: Moscow, Ankara, and Damascus.”

Furthermore, Turkey has become a cargo hub for European, Indian, African, and Latin American goods shipped to Russia. In 2022, the volume of freight transportation between the two countries spiked almost fivefold. In these conditions, blocking transit would make Moscow extremely vulnerable. The candidate who wins the election will be able to dictate the terms of cooperation with Moscow, argues Carnegie Center expert Pavel Krivosheev.

Blocking the cargo hub would make Moscow extremely vulnerable

Some experts are convinced that Ankara has already demonstrated the will to accommodate the EU's requests and limit the transit of goods to Russia. Early in March, the Turkish authorities suspended the transit of all goods through the country, including those under sanctions. Customs agencies rejected transit declarations citing a government decree. According to Reuters, the Turkish authorities had drawn up a list of goods under sanctions that were no longer eligible for transit to Russia starting March 1. However, two weeks later, the transit resumed. By a strange coincidence, it happened on the very day when the Russian MFA agreed to renew the grain deal. Unsurprisingly, many connected the dots and called the suspension of transit an attempt of pressuring Putin to extend the agreement that the Russian MFA had repeatedly criticized.

“Turkey won’t transport sanctioned goods to Russia except for ones it deems harmless. Moreover, I don't see how the upcoming election could change this position,” says Ceylan Ozgul. Even if the imports into Russia aren’t blocked entirely, sanctioned goods will become more expensive for Russians because such shipments will have to undergo customs clearance for further transportation to Russia as Turkish cargo. So whoever becomes Turkey’s next president, they will have another efficient tool for manipulating Moscow.