Suicide drone raids in Moscow have become business as usual, and repeated attacks on the same facilities vividly prove that, despite Russian propaganda extolling domestic anti-aircraft defense, Russian armed forces are in fact struggling to fend off Ukrainian air raids. The Insider addresses the most pressing questions about these drone attacks. How can Ukrainian UAVs make it to Moscow? What goals is the Ukrainian command pursuing? How can Russian cities defend themselves?

Content

Do Ukrainian drones often make it to Moscow?

What is the purpose of drone strikes on Moscow?

What we know about Ukrainian drones

How can Ukrainian drones even make it to Moscow?

Why can't Russian air defense take down drones as they approach?

What about Moscow? How come they aren't shot down in the city?

Can Moscow fully secure itself against suicide drones?

Should Muscovites brace themselves for new air raids?

Do Ukrainian drones often make it to Moscow?

The first UAV attack on Moscow dates back to May 3. Two drones exploded above the dome of the Senate Palace, the Russian president's official residence. May 30 saw the first massive strike. By a range of estimates, it involved from eight to 30 drones. Aerial defense intercepted most of them, and the rest crashed into trees or power lines. Some hit residential buildings, though.

On July 4, the media reported five drone sightings in Moscow. According to an MoD statement, four were taken down by the Greater Moscow anti-aircraft defense, and the remaining one was disabled by EW equipment near Odintsovo, a town outside Moscow.

The drone attack on the Kremlin, early May 2023

Since July 24, UAV attacks on the Russian capital have become regular. In less than a week, Moscow had at least five visually confirmed drone incidents. One damaged the roof of a defense ministry compound in Komsomolsky Avenue, adjacent to the headquarters of Fancy Bear, a hacker group affiliated with the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU).

Furthermore, drones raided the Moscow International Business Center (MIBC), also known as Moscow City, twice in three days: on July 30 and August 1. Both attacks hit the same high-rise building, IQ Kvartal, which hosts residential units and the offices of Russian ministries and public agencies: the Ministry of Economic Development, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Digital Development, the Federal Agency for Ethnic Affairs, the Federal Accreditation Service, and Federal Technical Regulation and Metrology Agency (Rosstandart).

On July 24 and 30 and on August 1, the Russian MoD reported disabling drones with electronic warfare systems and used the term “crash”, therefore explaining the resulting damage by its own actions.

What is the purpose of drone strikes on Moscow?

At the moment, the precise targets of Ukrainian drones remain unclear. Moscow and Moscow Region hold a great many military facilities, such as the strategic missile forces headquarters in Vlasikha, Odintsovo District, and various decision-making centers, such as the Senate Palace and, to some extent, the IQ Kvartal business center. However, aiming to damage, let alone destroy, any of these facilities with drones that carry so little explosives is a long shot.

Ukrainian military expert Leonid Dmitriev believes the Ukrainian command is indeed targeting legitimate military facilities (from military bases to defense enterprises) in and outside Moscow:

“Means of destruction used on the enemy's deep rear utilize purely practical coordinates of military targets or facilities that provide the enemy with certain capabilities in waging the war of aggression against Ukraine. In addition, they explore air defense capabilities along the route and other possibilities of ensuring such destruction.”

“Patriotic” Russian analysts perceive the attacks as Ukraine's attempt to draw Russia's anti-aircraft and EW defense away from the frontline to Moscow or destabilize the domestic situation.

The aftermath of the suicide drone attack on IQ Kvartal, Moscow City

This opinion resonates with an article by Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi and Mikhail Zabrodskyi, Supreme Rada deputy and former commander of the Ukrainian Airmobile Forces, published in September 2022. The authors argue that Russia's geographic remoteness facilitates impunity and the aggressive style of its war of destruction and propose attacks on the enemy's deep rear – the areas located far from the combat zone.

Volodymyr Zelensky has made similar statements:

“Gradually, the war is returning to the territory of Russia, and this is an inevitable, natural, and fair process.”

The Insider's sources in Ukrainian special services remark the raids pursue military rather than political objectives and aim to impede the functioning of Russia’s war apparatus.

However, no Ukrainian officials have claimed responsibility for the drone attacks; all we’ve heard are hints or jokes like “anyone can buy a drone in a military store”.

What we know about Ukrainian drones

There is no precise data on their technical specifications, such as their range or warhead size, or even designation. The New York Times insists the attacks involved at least three types of long-range UAV of Ukrainian origin: the Beaver, the UJ-22, and a “mystery drone”.

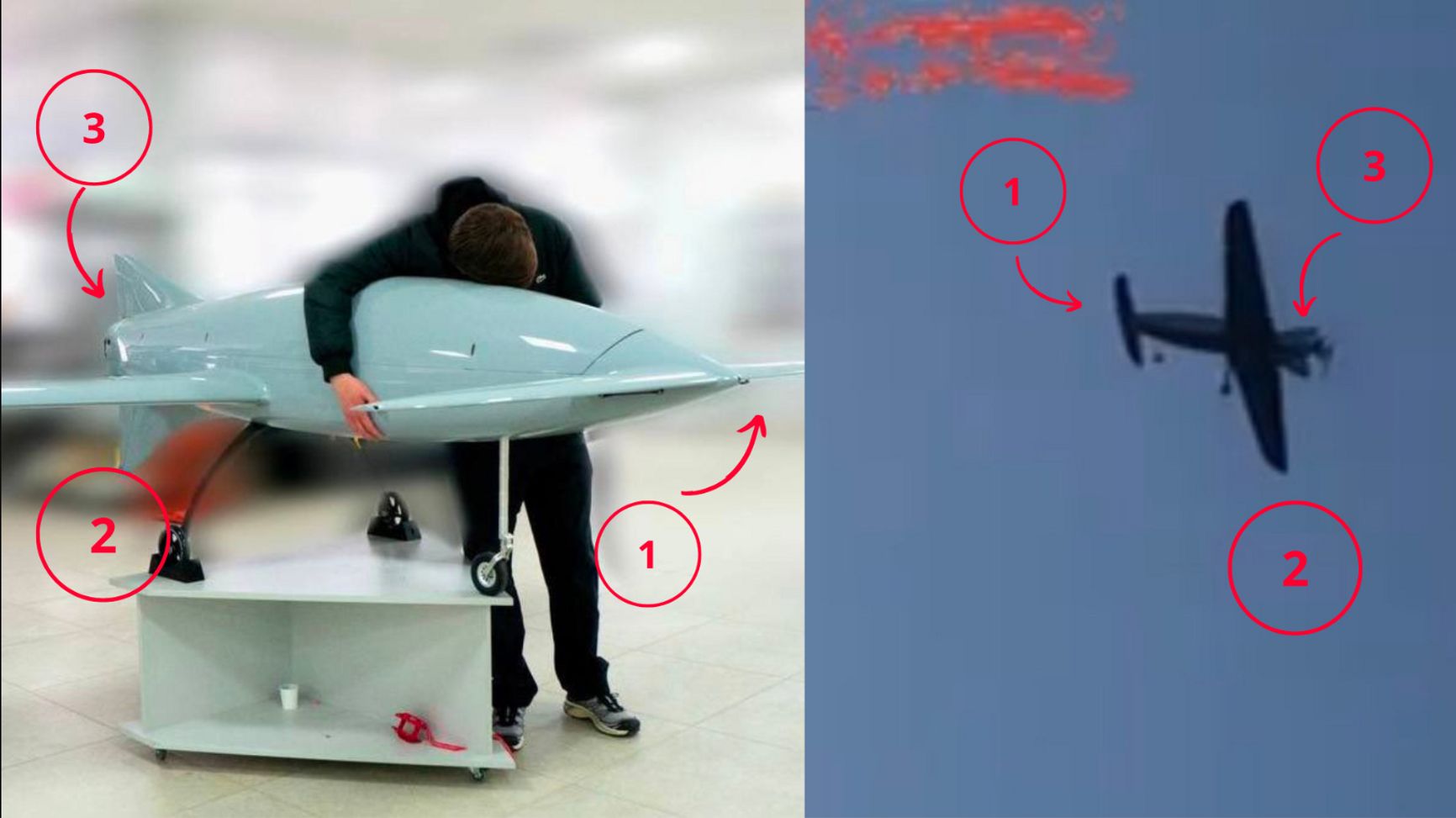

Ukrainian Beaver (front) and UJ-22 drones

The recent attacks most likely employed Beaver UAVs, which have a canard-type aerodynamic design. Indirect evidence suggests these drones are made from radar-absorbent materials and equipped with several types of navigation (satellite and inertial). They may support both land-based and catapult launching. A Beaver is presumed to have a range of 1,000 kilometers.

Considering that as many as two Ukrainian drones hit one and the same building in Moscow City in three days, they indeed feature a highly reliable and RFI-proof navigation system. Alternatively, the Ministry of Defense could be deliberately using its electronic warfare systems to redirect drones to Moscow City.

How can Ukrainian drones even make it to Moscow?

There are very few in-flight videos of Ukrainian drones, and the existing ones were shot close to the target: in or outside Moscow. One of the versions suggests that drones (or at least some of them) are launched from somewhere in the Moscow Region or an adjacent region, and not from Ukraine. In particular, this explains the success of the Kremlin raid in early May, when two drones hit the dome of the presidential residence in the heart of the capital, amidst a no-fly zone, with amazing precision.

A Beaver drone on the ground and in the air

That said, the size of the Beaver suggests it would have to be launched from Ukraine. State-owned Russian media agency TASS made this point citing a source after the August 1 attack. If we were to place the starting point on the Russo-Ukrainian border between the Chernihiv and the Bryansk regions, the crow-fly distance would equal 450 kilometers. It's not a huge challenge, even considering maneuvering and winds.

Why can't Russian air defense take down drones as they approach?

In a nutshell, it happens because Russia is too big a country.

The long answer is a bit more complex. Even the Soviet Union – a much more militarized economy and society – failed to ensure complete coverage of its vast territory with anti-aircraft defense systems.

According to the Ukrainian General Staff, around 460 Russian anti-aircraft systems of various types have been destroyed since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The Oryx OSINT project has verified the loss of 160 such systems; mostly close- and medium-range units designed to counter small-sized aerial targets. A recent video by a Russian military officer who complains of getting six malfunctioning Tunguska anti-aircraft guns (which were supposedly repaired) attests to the difficulties faced by Russia in filling the gaps in its air defense.

A Pantsir-S1 surface-to-air artillery system on the roof of the Ministry of Defense, Moscow

Considering the sanctions, the traditional challenges of Russia's military industry, and the need to keep some air defense systems on the frontline and in the tactical reserve, such losses render securing all of Moscow against aerial threats simply impossible.

Furthermore, a drone, especially one featuring stealth technologies, is a tricky target for anti-aircraft defense. Special materials make radar detection problematic, even though Beavers fly slowly at a relatively small altitude.

What about Moscow? How come they aren't shot down in the city?

Moscow started bracing itself for enemy drone attacks in the winter of 2022. The authorities began preparing sites for S-400 missile systems in suburban areas and parks, installing command systems and radar stations in Greater Moscow, and even placing Pantsir-S1 surface-to-air missile launchers right on the roofs in downtown Moscow. One such system was installed on the roof of the Ministry of Defense building in Frunzenskaya Embankment (for more details, read The Insider's feature story).

An S-400 missile launcher in the Losiny Ostrov conservation park

However, the MoD comments on the recent Moscow drone strikes use very particular language referring to electronic warfare systems. Those responsible for the capital's air defense avoid using Pantsir missile launchers in residential areas because of the inevitable risks for the civilian population, opting for EW means.

It’s impossible to verify whether a drone has been intercepted or disabled with an EW system because it crashes into something and explodes in any case. Jamming can only cause a drone to hit a different target.

Leonid Dmitriev agrees that Russian air defense has been trying (and failing) to use EW systems to make up for the shortage of weapons and radar equipment:

“Lacking in anti-aircraft weapons and sensing capabilities, Russia is instead using electronic warfare means. However, the use of EW systems in densely populated areas with high-rise buildings is both criminal negligence and a sign of Russian air defense being unable to hit small-size aircraft on an approach to the city or in its air space.

EW systems perform two functions: they either intercept a drone for its secure landing or disable its control to send it into uncontrollable flight until it's taken down or crashes into an obstacle. However, since Russian air defense weapons are notoriously inefficient against small objects, an uncontrollable drone will most likely ram into a building. As a result, Moscow has lately been using its multi-story buildings as physical air defense.”

By contrast, Ukrainian anti-aircraft systems are regularly taking out Russian UAVs above Kyiv, as evidenced by recent eye-catching photos.

Can Moscow fully secure itself against suicide drones?

Vladimir Putin assessed the performance of Russia's air defense as “satisfactory” following the May 30 raid:

“Moscow's anti-aircraft defense system provided an expected, satisfactory response, even though there's room for improvement.”

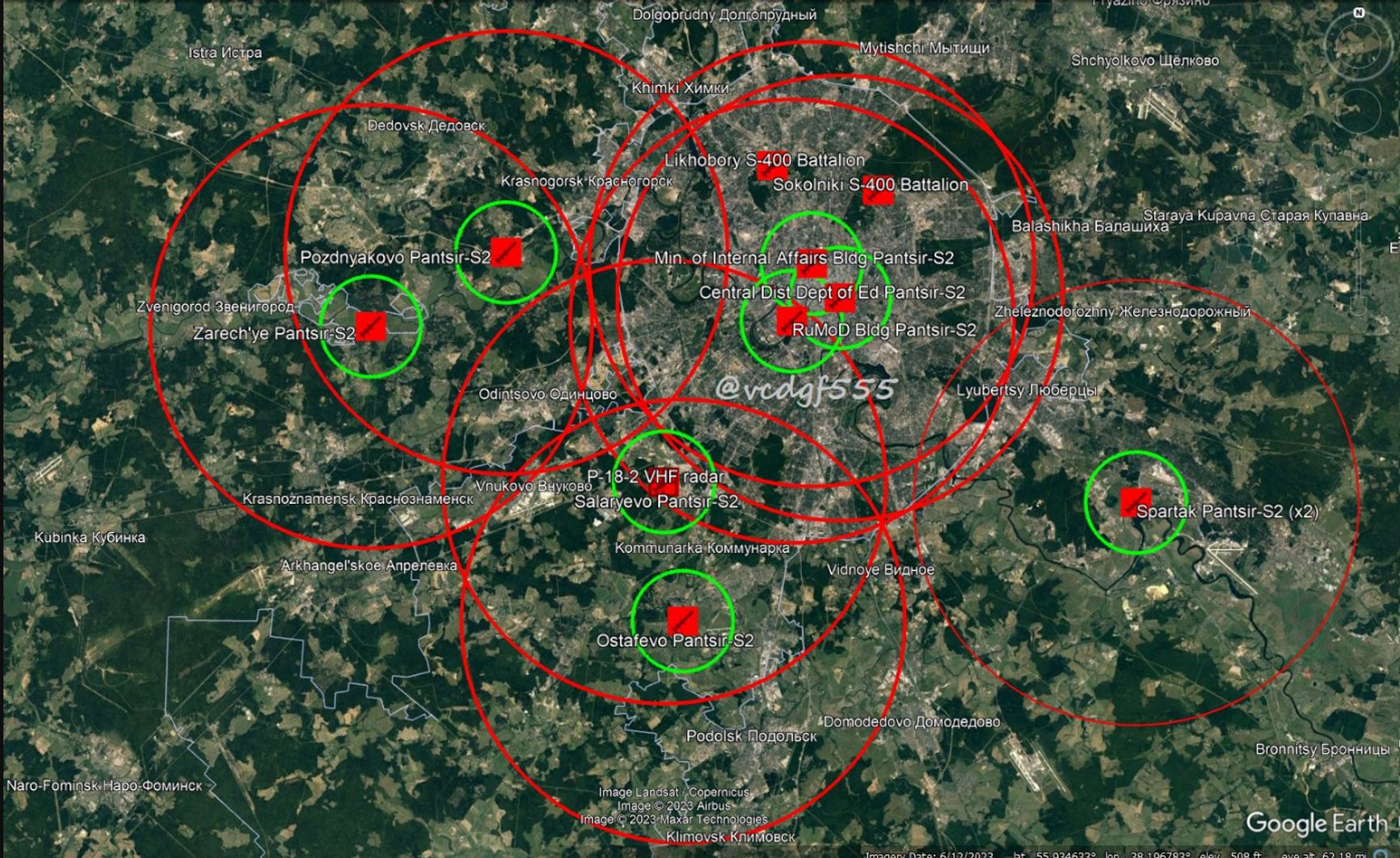

The improvement of Moscow's air defense is best summed up by the following images. The map of surface-to-air missile launcher coverage of the Russian capital as of January 2023.

The same map as of July 2023:

But no matter how many Pantsir and S-400 systems you plant in and around Moscow, you can't cover all possible drone routes.

As Leonid Dmitriev aptly put it, “The performance of Russia's domestic air defense is satisfactory for the Ukrainian side of the conflict instead of serving the interests of the aggressor state.”

Should Muscovites brace themselves for new air raids?

Indeed they should, and they should prepare for much bigger attacks.

Leonid Dmitriev believes that “with each day of the war and with each destroyed air defense system, Russia’s air space is becoming more and more vulnerable” to drones, so they will become a much more frequent sight in the Moscow skies (and beyond). Ukrainian volunteers Serhiy Prytula and Serhiy Sternenko certainly hint as much in a recent video: naming Russian cities (a popular word game in which you have to come up with a word, e.g. the name of a city, that starts with the last letter of the previous word) with canard-shaped drones in the background, one says “Arkhangelsk” (which is in the far north), and the other responds, “It probably won't fly that far.”

A still from an AFU video hinting at the August 24 raid

As The Wall Street Journal writes, the latest attacks on Moscow could be staging a truly massive raid from multiple directions and at several altitudes. The Center for Strategic Communications of the Armed Forces of Ukraine posted a video on July 30, suggesting that one such attack could be planned for August 24, Ukrainian Independence Day. Sources in Ukrainian special services have also confirmed that Russia should prepare for a series of such raids.