The village of Mulino in Russia’s Nizhny Novgorod region is a major training center for soldiers — both contract servicemen and conscripts — heading to the war in Ukraine. Mulino is also home to Europe's largest training facility for artillerymen, and is the birthplace of the 3rd Army Corps, a formation composed of thousands of mercenaries which faced significant losses near Kharkiv in the fall of 2022 and near Bakhmut this spring. The local soldiers, however, are not known for their “feats” on the battlefield, but for the way they terrorize the village: they set fire to a church in April this year, and cut off a cab driver’s finger in June. The military’s incessant drinking and rampaging has become a real nightmare for the locals. Mulino residents have even asked the Nizhny Novgorod governor to enforce a “dry law” and keep the military from leaving their bases, but neither seems likely to happen anytime soon.

Content

“Your finger or your life”

“Halt, gunfire!”

“It's very wild for us — they act like bums!”

“They drink in droves, lying everywhere”

“Graveyard for soldiers”

“We came to pray, but the church was torched by the military”

“Your finger or your life”

“I begged these soldiers, I told them I have children, a family. I have nothing on me, let's go back to the village, I’ll compensate you for everything,” says 50-year-old cab driver Abbas Ali. “He grabbed [a knife] and said: your finger or your life? I said: my finger, of course. He put my little finger on a pile of logs and sliced it off.”

Abbas Ali, a Mulino resident, had a harrowing experience when he agreed to take young soldiers from the military camp to a sauna in nearby Dzerzhinsk. The night trip almost cost him his life. The request came from a friend, and Abbas agreed, as the fare would have been a good score, totaling at least 1500 roubles ($16) for a one-way trip at night.

On the way, the soldiers, who were already tipsy, asked the driver to stop at a store and bought more vodka. On a section of the federal M7 highway, a moose jumped out onto the road — the animal was young, but large enough to shatter the car’s windshield. According to the driver, “the animal's innards soiled the uniform of the soldier riding in the front seat.” The enraged passengers took the driver to a forest in his own car, and dragged him out, threatening to kill him. The group then severed his finger and violently beat him. Abbas Ali, the cab driver, suffered broken ribs, a concussion, lung damage, and multiple hematomas. Once the violence was over, the man was warned: “If you report [any of this], we’ll kill you.”

The authorities quickly detained all four men. Two of them were recognized as witnesses, while the other two were taken into custody and became the subjects of a criminal investigation for robbery. Local media were afraid to mention that the cab driver's torturers were actually soldiers, and at least one of them — 22-year-old Denis Kozharin — had returned from Ukraine.

The Ukrainian Telegram channel Radikalnya claimed it had hacked Kozharin's page on the social network VK, and released his correspondence with two women, where the soldier describes cutting the heads off of Ukrainian prisoners of war. “We do not take them prisoner. All those we catch, we disarm. And [then] we kill them,” the chat reads. “I have a video where they filmed me cutting off the head of a Ukrainian.”

Sources in the military confirmed to The Insider that he had indeed fought in Ukraine, but denied the authenticity of the correspondence. Victoria, who had conversations with the soldier, said that the messages were forged by unknown individuals, and described Denis as a “very good and kind person.” “What happened (to him and the cab driver) is a big mistake and an accident,” she added.

The Insider has no data at its disposal to confirm or deny the authenticity of this conversation

The Insider has no data at its disposal to confirm or deny the authenticity of this conversation

The Insider has no data at its disposal to confirm or deny the authenticity of this conversation

The “mistake” has been and continues to be widely discussed throughout the Nizhny Novgorod region. Residents of Mulino, Volodarsk and Dzerzhinsk are outraged that the charges were too mild. “What are these two witnesses? All four are guilty. This is already a group. And attempted murder. At the end, they scored and fled, leaving the man to die,” — these kinds of comments flood social networks of groups and chat rooms in the region.

Local residents are outraged that the cab driver's torture was prosecuted as a mere robbery

During my journey with a cab driver from Nizhny Novgorod to Mulino, I as if he's concerned about taking fares from soldiers after such incidents.

“I think there are plenty of fools everywhere. It's not only in Mulino that you can get into trouble. In any neighborhood, in any city, you can get clients like this. I try not to be negative,” the driver says, while I recall that criticizing those involved in the so-called “special military operation” is forbidden in Russia.

“Halt, gunfire!”

We drive past several military units, a firing range, and another range with mock-ups of military equipment. While the village of Mulino is accessible, the surrounding forests and fields are off-limits to the public as they belong to the Defense Ministry. Mulino has a long history of military training dating back to tsarist Russia, thanks to its well-suited terrain.

Almost all the forests and fields around Mulino are occupied by Defense Ministry facilities

“We often come across tanks during exercises. On the right side is the training ground, and on the left is a portion of it. It's best to avoid going into the forests along the road,” the driver says with a grin. The area is now home to Gorokhovetsky — the Russian Ground Forces’ largest military training ground, which is surrounded by numerous bases. These include the 47th Tank Division, the 288th Artillery Brigade, and two training centers — the 681st Regional Training Center for Combat Training of Rocket Troops and Artillery and the 333rd Combat Training Center. There’s also the 28th Separate Disciplinary Battalion, where military personnel convicted under criminal articles are kept.

As we exit the M7 federal highway, we're met with cautionary signs on both sides of the road: “Halt, gunfire! Passage and transit forbidden!”

Both signs are duplicated in English. We drive on, passing two tank crossings along the route.

The road to Mulino

The winding road from the highway to Mulino is notorious for frequent accidents. Cameras and accident patrols are lacking, and locals — both civilian and military — regularly get behind the wheel drunk, says the driver. “Recently, a car drove into my lane from the opposite side of the road,” says the cabbie. “I hit the brakes and honked the horn, but he didn’t react. I was driving a guy in the military. We stopped, got out, looked at the driver, also a military man — he was drunk as hell. The passenger told me: ‘So what? It's Mulino!’”

The village itself is home to 14,500 people, mostly military personnel, as well as their families and relatives. Mulino is divided into two parts, which the locals call “towns” — the “new town” was built in the 1990s, while the “old town” has buildings dating back to the 1950s. That's where we’re headed: old town residents complain about soldiers' behavior most of all, demanding that the military are barred from leaving their units in the evening and that a “dry law” — a complete ban on the sale of alcohol — be enforced in the area.

“It's very wild for us — they act like bums!”

“Hey, look! The Wagnerites [members of the Wagner Group] are out there showing off!” laughs a man in military attire, peeking from the supermarket door. He holds a bag of groceries in one hand and a working walkie-talkie in the other, which occasionally bursts alive with unintelligible phrases and obscenities. The smokers at the entrance to the store — ten soldiers — turn around at the voice. Ten soldiers smoking at the entrance turn to hear him. “Wagnerites? No way, you're mistaken. Wagnerites don't show off,” one soldier responds. “Yeah, right, whatever,” grins the man with the walkie-talkie, takes a puff of his cigarette, and walks away towards the market.

Pyaterochka — one of Russia’s largest supermarket chains — is located in Mulino’s old town. There are crowds of soldiers here: aside from being a grocery store, the supermarket acts as a social hub of sorts for military men from around the area. While some civilians also come out for evening strolls along a nearby street, they seem to avoid lingering near the supermarket.

The group of “show-off Wagners” — mocked by the man with the walkie-talkie — comes out of the store. One of the soldiers has a large tattoo on his forearm, resembling an eight-rayed rotor, which is associated with the “Slaviс” version of the swastika, often used by neo-pagans, Russian neo-Nazis, and the far right. The same symbol can be seen on the emblem of the “Rusich” sabotage and assault reconnaissance group (headed by neo-Nazi and animal abuser Alexei Milchakov, who likes to be photographed with the severed heads of puppies and the severed ears of captured Ukrainian soldiers). Two uniformed soldiers sit on concrete blocks nearby, appearing to struggle to get up. There are two bags with food and alcohol nearby, along with scattered garbage on the ground.

Alyona T., a Mulino resident, had recently worked as a saleswoman in one of Mulino's nalivaykas [small stores selling cheap draft beer and other alcohol — The Insider] but she never got used to the crowds of drunk soldiers. Her husband insisted she leave her job — he is a military man himself and works at one of the bases, training soldiers. Like many of the village residents, he is not happy about those who are brought to Mulino after the beginning of the war in Ukraine. Alyona and I chat outside a panel five-story building across from Pyaterochka. She tells me that women and children avoid walking alone in the dark as they are afraid of drunken military men — especially volunteers who are going to war in Ukraine, as well as those who have returned from it.

Women and children avoid walking alone in the dark, fearing drunk soldiers

“We are not used to this kind of society here! It's very wild for us!” — Alyona complains. According to her, before Russia invaded Ukraine, the servicemen were more reserved, and behaved more decently. “Now they’re just like hobos, I don't even know where these people live. I’ve traveled across the country, I have many relatives in small towns and villages, but I’ve never seen such behavior.”

The main topics of conversation at Pyaterochka are the war in Ukraine and Yevgeny Prigozhin's mutiny. In one car, the driver plays an official's speech about humanitarian aid to the front line. Military men stand out in the crowd, closely observing the situation, while others come out of the store with cans of beer and bottles of cognac. Alyona assumes some soldiers are assigned to keep order in places where drunken soldiers gather. These patrols were introduced after the first outburst of discontent from locals in the summer of 2022 — when the first batch of volunteers arrived in Mulino.

Pyaterochka isn’t Mulino’s only popular store — the Magnit supermarket is close by, as well as several other stores selling alcohol, such as the popular chains Bristol, Red and White (“Krasnoe I Beloe”), and multiple nalivaykas. As darkness falls, the soldiers leave towards the local market or the forest. The old part of Mulino is practically a large pine forest itself — trees are everywhere, even in private courtyards, and empty vodka bottles can be found on benches and stumps.

“They drink in droves, lying everywhere”

Alyona, who now works as a beautician after leaving her job at the store, lives in Mulino’s “new town.” This newer part of the village is filled with modern “Finnish-style” five-story buildings. The neighborhood was established when the 34th Guards Artillery and 47th Guards Tank Divisions were relocated from the GDR to the Gorokhovets training ground after Germany's reunification. It was built to accommodate families of servicemen, with the construction carried out by North Korean workers. Today, their barracks — which used to be surrounded by barbed wire — have been replaced by garages.

Although Alyona's office, where she offers her services, is less than 500 meters from her home, the distance turned into an obstacle course in early fall 2022, as she had to navigate through crowds of drunken military men. While she was not surprised by the presence of soldiers — she had lived in Mulino for several years, and was used to the presence of people in uniform, the arrival of volunteers following the Russian invasion of Ukraine left her terrified.

“It was so scary. I was just terrified to walk around. When I was alone in the evenings, when it was getting dark, and I was working until seven, eight, nine o'clock... well, in general, I was having a hard time,” she told The Insider. “There was a big crowd of them down here, and I thought: how can I go out? I have to go around them somehow.”

Buying alcohol in Mulino

According to Alyona, Mulino saw three waves of servicemen come through the town after the beginning of the war. The first wave was made up of volunteers, who appeared here in the summer of 2022. All of The Insider's sources from among the local population called them “completely deranged.” They complained of drinking, fighting, stealing, as well as molestation and harassment.

“It sounds really rude, but it's like society spit them out. I can't even put it any other way. They stand here in the morning... I once ran to Magnit before work,” Alyona waves her hand in the direction of the store. “And here I see [a soldier] slumped over, pants half-unbuttoned, underwear out, drinking something. And there are a lot of them!”

In response to the complaints, the local authorities took action, and in October, the governor of Nizhny Novgorod issued a decree prohibiting the sale of alcohol in Mulino. The move resulted in a period of relative calm. However, a month later, the sale of alcohol resumed.

Russian soldiers in Pyaterochka in Mulino's "old town"

“I then also resented the dry law, I thought, well, if it's my birthday, how can I celebrate with my friends without alcohol?” — Alyona recalls. “But when the sale was allowed again, I realized that I was angry for nothing. When it was banned, there were no soldiers in the stores at all. And now there are huge crowds again and they just bring out boxes of vodka, cognacs.”

In the summer of 2022, volunteers in Mulino were assembled to form the 3rd Army Corps — specifically intended for participation in the invasion of Ukraine. In late August, photos emerged showing military equipment being transported by rail from Mulino to the Rostov region. These trains carried T-80BV and T-90M tanks, as well as the Buk surface-to-air missile system. The volunteers were reportedly training at a large combat center in Mulino, built by the German defense company Rheinmetall for Russia's Ground Forces.

The second “invasion” began after Vladimir Putin announced mobilization, says Alyona:

“There are a lot of mobilized [men], some of them were completely deranged. They drink in droves, lying everywhere. Literally! Especially where the stadium is, in the woods, in the old town. Sometimes we go to work in the morning, and there are bodies everywhere. We don't have that in the new town. We're a military village, and it's strictly monitored — I mean, it used to be. It's rare to get this drunk here. And look at things now! Now it's more decent, the mobilized people seem to behave better, but there are still a lot of them, and they drink.”

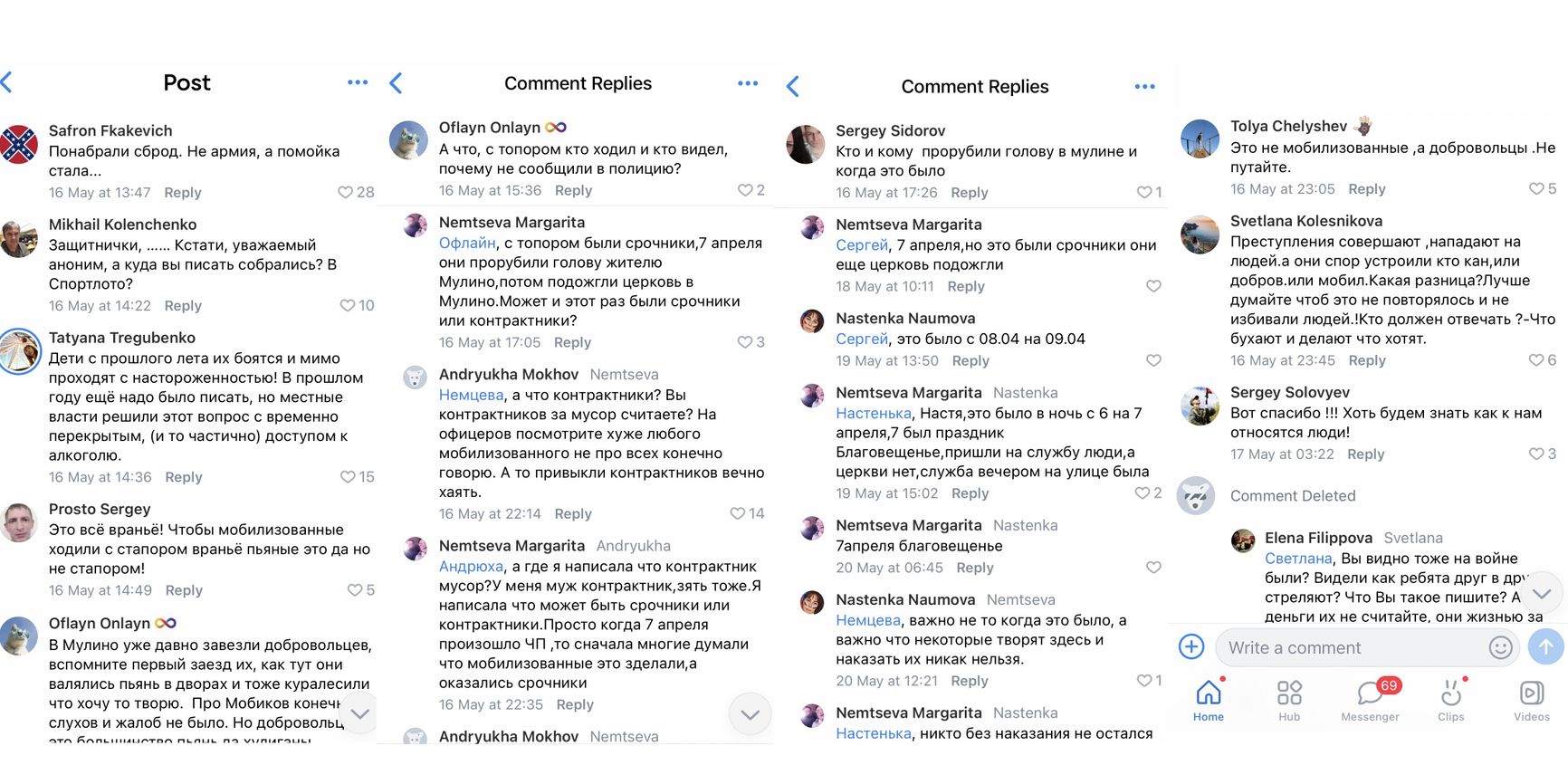

However, in the district social networks, residents discussing the behavior of the military call the mobilized more disciplined than the volunteers.

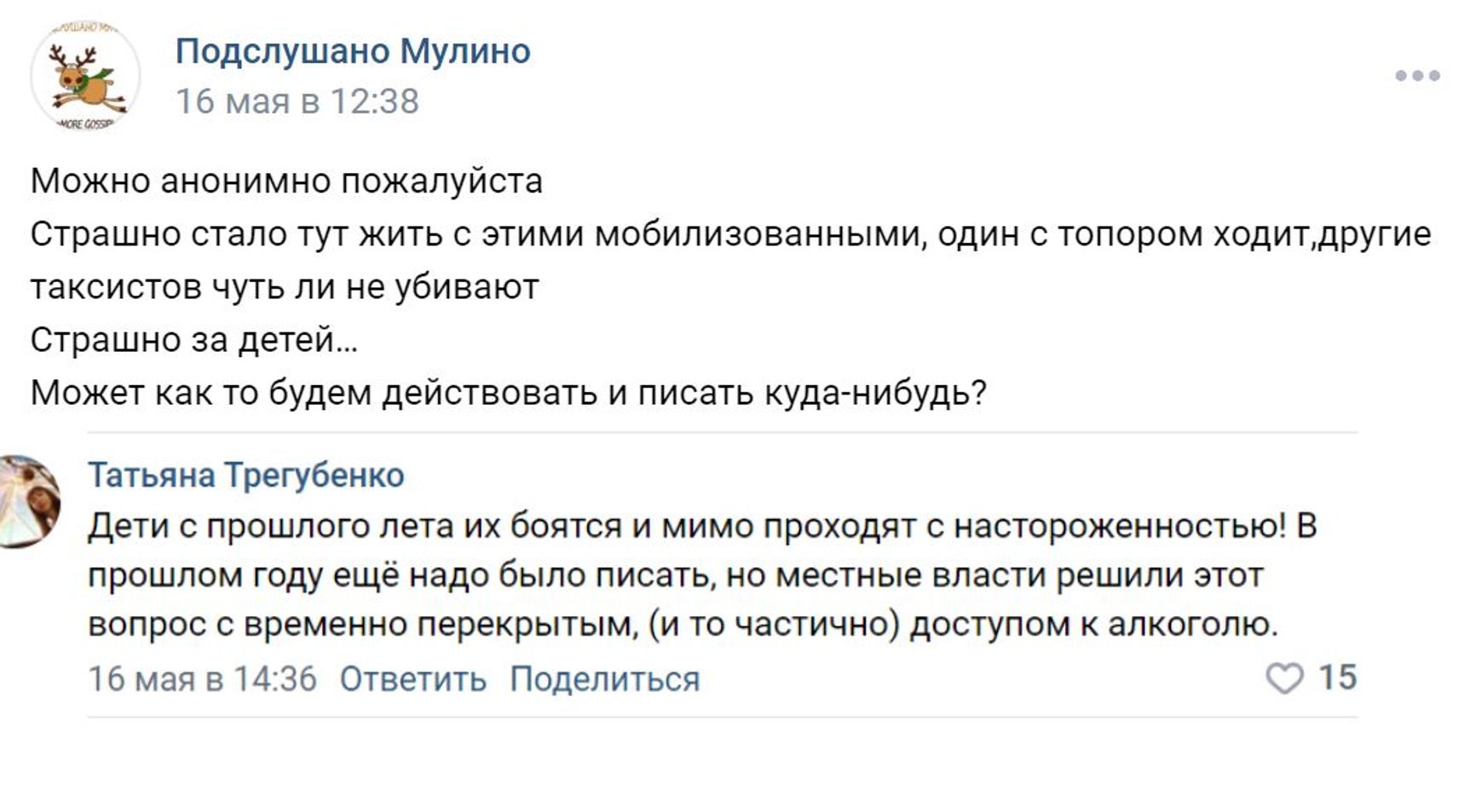

The third wave of soldiers arrived in Mulino in the spring of 2023, made up of contract soldiers recruited from various parts of Russia. Once again, complaints surfaced about the presence of drunk military men “bringing out vodka and cognac.” In May 2023, one of the residents took to the social network VK, and appealed to the head of the region, Gleb Nikitin, requesting the prohibition of alcohol sales in Mulino once more.

“Summer vacations are coming up, and we fear for our children's safety if they go out alone. I've witnessed drunk individuals harassing young mothers and children multiple times, and I had to threaten them to back off. We lack proper law enforcement here, and it's frustrating to see the behavior of some volunteers and mobilized personnel. They should focus on their duties in the [‘special military operation’] rather than causing trouble in our community.”

A soldier in Mulino's “new town”

“Children have been afraid of them since last summer, and pass by them with caution,” echoed resident Tatyana. Despite the appeals, authorities in Nizhny Novgorod did nothing to restrict alcohol sales, and the military freely bought booze from local stores.

“Graveyard for soldiers”

Military-related emergencies in Mulino are a regular occurrence. In October 2022, a 45-year-old mobilized man lost his life during exercises at the training ground. According to documents, he died from multiple fractures caused by “compression between objects.” His son claims that the military ignored safety procedures and towed the stalled tank while his father was on its turret. The tank hit a bump, causing the turret stopper to come off.

“Two crew members managed to jump off, one was injured, and my father died on the spot. He, as we think with my mother, fell into the space between the muzzle and the tank's armor... But only the officers know the whole truth.”

Another serviceman, a contract soldier from Chelyabinsk, died in Mulino on February 23, 2022 — the day before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. At the time, Russia’s Defense Ministry claimed 21-year-old Pyotr Bochkarev was poisoned by surrogate alcohol. But the soldier’s mother believes her son was poisoned with antifreeze, as he wanted to go public about the abuse he had experienced in the army.

21-year-old Pyotr Bochkarev, died in Mulino on February 23, 2022

“The rotten army killed my son, he was poisoned at his unit in the rotten Mulino in the Nizhny Novgorod region. [The army] kept him there for twenty-four hours, covering their asses; when they realized they couldn't save him, they took him to a hospital in Moscow in an ambulance for five hours. Everything happened on January 23, and on February 4 at 23:50 my little angelic son was gone,” wrote his mother Olga Bochkareva on social media.

Before his death, her son spoke about chaos and violence in his military unit, says Olga, and was going to quit, but could not do so in time. “Mulino is a graveyard for soldiers,” Olga tells me. “They took away their things, and forced them to make money transfers from their accounts to some girls.”

Coverage of the anarchy in Mulino even made it to Russian pro-war Telegram channels:

“Contrabasses [a nickname for contractors in the Russian army — The Insider] and officers of the 26th Tank Brigade at military base 52562, Mulino, you don’t need to take equipment and first aid kits from the mobilized — which they bought at their own expense. Have you gone completely mad?” — wrote the author of the channel Arkhangel Spetsnaza (“Archangel of the Special Forces”), which has over 900,000 followers.

“We came to pray, but the church was torched by the military”

In Mulino are trained mobilized, volunteers, contract workers, according to some reports, there were also mercenaries from the Wagner Private Military Company — in Nizhny Novgorod, students at Minin University complained to the governor in June that the Wagner mercenaries had moved into their dorms.

In June, students at Minin University complained to the governor that Wagner mercenaries had moved into their dorms

Conscripts are also present in Mulino, and are generally seen as the least problematic group. However, according to residents, it was conscripts who set fire to a small church in the village — the Church of the Great Martyr George — on the night of April 7. Two servicemen went AWOL and sneaked into the church building at night. It is unclear as to how the altar caught fire — perhaps the alcohol the soldiers had already drunk was not enough to keep them warm. One of them was so drunk that he did not wake up and died in the fire.

Aftermath of the fire at the Church of the Great Martyr George in Mulino

“We came to the service on the Annunciation, and the church was gone. The service ended up on the street in the evening,” says Svetlana, a Mulino local.

After every incident involving military personnel, whether it's theft or harassment, disputes arise among Mulino locals on who is to blame: conscripts, contract servicemen, or volunteers. The authorities conceal all emergencies involving the military, providing only limited and vague information. Locals often find out the details through online chat rooms or directly from each other.

The authorities conceal all emergencies involving the military, providing only limited and vague information

“It turned out that it was the conscripts — on April 7, they split the head of a Mulino local, and then torched the church,” — says Mulino resident Margarita. “At first, many people thought it was contract soldiers, but then they figured it out.”

“What difference does it make if it was the mobilized or volunteers? It’s dangerous to live in Mulino! Dog attacks happen in broad daylight, and people seem to have lost all sense of reason, attacking without fear, as if they’ve seen it all. It's time for patrols, it's a military town, after all!” — user Ruslan Fedotov wrote in a local social media group.