Russia is supported in its war against Ukraine by a coalition of rogue nations. Iran supplies combat drones, North Korea provides shells and missiles, while Venezuela and Nicaragua unabashedly endorse and justify the Kremlin’s unprovoked aggression. Myanmar, a relatively small state in Southeast Asia, is not often mentioned in the company of the international rogue’s gallery—this despite its extensive history of arms and military equipment purchases from Russia. Now, however, the ruling junta in Myanmar has begun sending a portion of that military hardware back to Moscow, along with mines of their own production.

Content

USSR and Burma, brothers in arms

From Chinese tanks to contracts with Russia

Communists, minorities, and other rebels

Playing the democracy card

Not the highest level

Re-export of weapons from Myanmar to Russia

USSR and Burma, brothers in arms

In 1955, Roman Karmen, a luminary of Soviet documentary filmmaking, unveiled “On the Hospitable Land of Burma,” which chronicled the visit of Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev and Prime Minister Nikolai Bulganin to the country now known as Myanmar. The film features a notable scene, set in the residence of Burmese Prime Minister U Nu, in which the silent presence of U Ne Win, Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese Armed Forces, is clearly visible. Little did anyone present in the opulent residence anticipate that U Ne Win would emerge as the orchestrator of a new political epoch in his country’s history — one that would outlast both the protagonists of the film and its creators, and which would ultimately extend to its direct military support of a future occupant of Khrushchev's Kremlin office.

In 1958, U Ne Win assumed the helm of the Burmese government through ostensibly democratic means, backed by free elections and the patronage of the retired U Nu. However, the nuances of functioning within the confines of electoral democracy — contending with an active opposition, coupled with the perpetual threat of losing power — seemed incongruent with U Ne Win's disposition. Consequently, by 1962, the general masterminded a coup, preemptively consigning his predecessor, towards whom he had smiled so amicably in the Soviet film, to imprisonment.

From Chinese tanks to contracts with Russia

In 1988, the Burmese junta’s brutal crackdown against peaceful protesters demanding the democratization of the state resulted in the imposition of international sanctions against the regime. Neither Gorbachev’s fading Soviet Union nor Boris Yeltsin’s fledgling Russian Federation were prepared to go against the wishes of the international community for the sake of the impoverished, authoritarian state that, in an attempt to whitewash its international image, in 1989 officially change its name to Myanmar.

Neighboring China, however, was prepared to fill the void left by the political changes in Moscow. Beginning in the early 1990s, large quantities of tanks and howitzers began flowing across the border, but with one unpleasant condition for Myanmar’s ruling generals: in exchange for military supplies, Beijing demanded concessions for Chinese companies in Myanmar, coordination with the PRC on various foreign policy issues, and even the elimination of the Dalai Lama (whom the Chinese leadership considers to be the leader of Tibetan separatism) from Myanmar’s information space.

The nominally Buddhist Burmese generals reluctantly complied. However, in addition to the political and economic dependence that came with every new package of Chinese military aid, Myanmar's generals were also displeased with the lower-than-expected quality of Chinese tanks and armored vehicles. As a result, in the early 2000s Myanmar began procuring weaponry from Israel, the states of the former Yugoslavia, and India. The country also partnered with Ukrainian specialists in order to establish its own armored vehicle production facilities.

However, the junta's efforts to break free from Chinese dependence brought the lion’s share of benefits to Russia. In the first decade of the 2000s, Myanmar received Russian MiG-29 fixed-wing aircraft along with Mi-35 and Mi-17 helicopters. The junta funded the training of thousands of its officers in Russian military academies, and defense enterprises in the Russian Federation secured orders for the production of ammunition and spare parts for the distant Asian country. Over the twenty years from 2001 to 2021, Myanmar officially paid Moscow $1.7 billion for the fulfillment of military contracts. For a country where the average monthly wage barely exceeds $300, this is quite a significant sum.

From 2001 to 2021, Myanmar officially paid Moscow $1.7 billion for the fulfillment of military contracts

Communists, minorities, and other rebels

The weaponry — along with the cadres of officers trained in Russian academies — proved indispensable to Myanmar’s military authorities as they grappled with insurgent movements still unwilling to accept the eradication of all political freedoms. In the years immediately following the 1962 coup, Chinese-backed communists largely headed up the insurgency, but within a few years, Beijing ceased its support for the red partisans in exchange for political concessions from the junta, along with lucrative economic contracts. The waning support from China did not halt the ongoing jungle warfare, however, and the role of communists as leaders in the armed struggle against the state authorities was swiftly assumed by militias comprised of members of ethnic minorities.

Myanmar is a diverse country, with the titular Burmese making up a minority in some regions. Nevertheless, in the corridors of power, no other group is adequately represented. Discontent with this situation soon after the junta's takeover led to the resurgence of separatist sentiments that had smoldered since colonial times (from 1824 to 1948, Burma was part of the British Empire). Separatists from the peripheries found support from various pro-democracy forces and even armed groups of students. Consequently, sporadic bloody conflicts flared up throughout the country.

The 1988 protests compelled the junta to break from the practice of controlling the country through unconditional violence and instead to attempt dialogue with the opposition. Over two million people participated in these protests across the country, posing a real threat to the military's power for the first time in its entire rule.

The 1988 protests in Myanmar

Although the protest wave was ultimately suppressed by the regime’s long standing weapon of choice — force, which killed anywhere from several hundred protesters to several thousand, depending on the source — the military still had to make several concessions to forestall any new attempts at a popular uprising. It was for this reason that the head of the junta, the same U Ne Win who made the cameo appearance in the 1955 Soviet documentary, resigned, giving his consent to conduct the country’s first multi-party parliamentary elections since the 1962 coup.

Playing the democracy card

The elections took place in 1990, and the victory went to the National League for Democracy (NLD), a political force led by one of the iconic figures of the protest movement, Aung San Suu Kyi. However, the military refused to allow the NLD to take power. Instead, the junta simply annulled the election results and arrested or sent into exile the most active opposition figures. Aung San Suu Kyi herself remained under house arrest for many years. She was not even released to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, awarded to her in 1991. In total, the politician spent about 15 years of her life in confinement, a period marked by intermittent releases followed by subsequent re-arrests.

Aung San Suu Kyi

Throughout these years, the world pressed the junta with demands to release the opposition leader. Even the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, flew in for negotiations with the generals.

Under pressure from external actors and internal circumstances, the generals ultimately allowed her to return to politics. Aung San Suu Kyi was even permitted to form a government based on the parliamentary election results of 2015, which the NLD won with over 57% of the vote.

However, it was not the victory of democracy over the military junta that many at the time were hoping for. The officers did not retreat from politics, but remained in parliament, in government, in crucial administrative positions, and in control of Myanmar’s myriad security forces. Not just the army but also the police answered not to civilian officials but to the generals. And Aung San Suu Kyi herself, as subsequent events revealed, could only operate within the limits permitted by the military.

Aung San Suu Kyi herself could only operate within the limits permitted by the military

Thus, when the military began the forcible deportation of predominantly Muslim Rohingya people in 2016–2017, the civilian government did not stand up for the victims of the rampages organized by the generals. At that time, there were even calls to strip Aung San Suu Kyi, who to all appearances turned a blind eye to the ongoing genocide, of her Nobel Prize. Internationally, notably less noise was made about the junta’s use of Russian aircraft in its attacks on Rohingya villages.

The deportation of the Rohingya was labeled as genocide

Despite the humanitarian catastrophe it nominally presided over, the civilian government did not collapse until 2021, after parliamentary elections in 2020 delivered the NLD an even larger majority than it had received five years earlier. This time, however, the military was not prepared to share power. Rather than acquiescing to the results, it staged yet another coup, declaring that the vote had been falsified and thereby stripping away even the facade of democracy. Aung San Suu Kyi and her associates were thrown into prison, and their supporters were outlawed. The standoff quickly escalated into a full-fledged civil war, one that shows no sign of ending in the foreseeable future.

Not the highest level

Leading the new military government is the Army Commander Min Aung Hlaing. Mere weeks after the coup, the general gave an interview to the Russian newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets in which he praised the leadership of the Russian Federation and promised that the friendship between the two countries would last forever.

A couple of weeks after the coup, the general gave an interview to the Russian Moskovsky Komsomolets newspaper, praising the leadership of the Russian Federation

The leader of the junta, whose relationship with Moscow began well before the coup that brought him to power. turned out to be a genuine Russophile. Between 2013 to 2020, Min Aung Hlaing visited Russia four times, returning with signed contracts for the supply of new aircraft, missile systems, and armored vehicles. Given that history, it is not surprising that one of the general’s first foreign visits in his new capacity was to Moscow. He made a second trip there just a few months later.

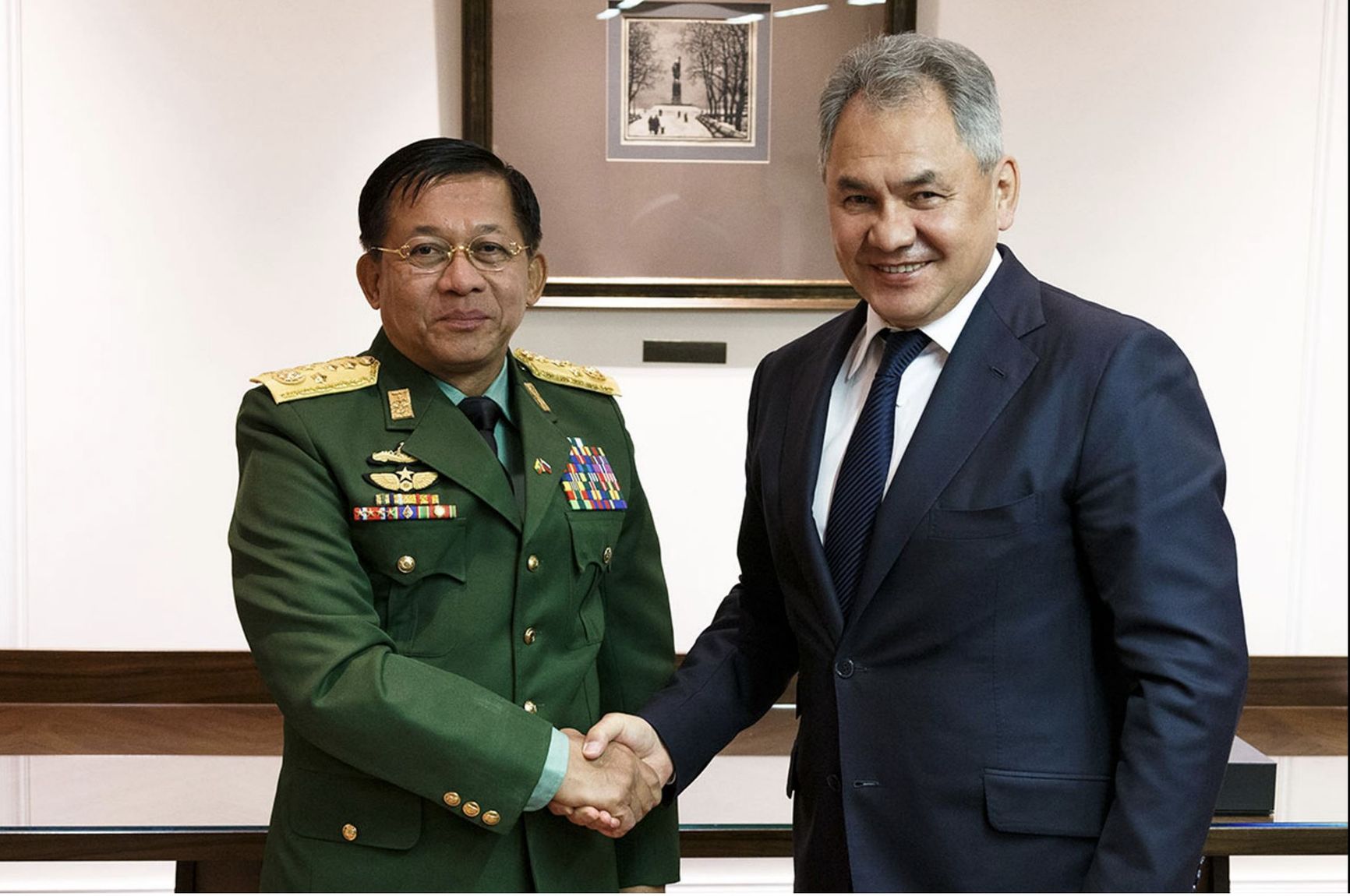

In Russia, Min Aung Hlaing was received at a fairly high level, but still not the highest. He spent time with the Foreign Minister and the Defense Minister, but not with the President. Presumably, the difference in the status of the two leaders played a role. Min Aung Hlaing was an obvious usurper of power, unrecognized by the international community and suffering, among other political handicaps, from personal sanctions.

At that time, Putin could still behave as if he were the legitimately elected leader of a major world power. For the former intelligence officer in the Kremlin, the Burmese general was certainly an ally, but not a figure of utmost importance. Besides, their official ranks did not even match. Although Min Aung Hlaing was the de facto head of government back home, de jure Myanmar’s head of state was the puppet president Myint Swe, a retired general who was temporarily installed in power following the February 2021 coup. Perhaps Putin simply disdained to meet with someone who was lower than he in the political hierarchy.

Min Aung Hlaing and Sergei Shoigu.

Vadim Savitsky

Re-export of weapons from Myanmar to Russia

Everything changed with Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which, unsurprisingly, the junta supported wholeheartedly. Throughout the civilized world, the events of February 2022 quickly turned Putin into an outcast. By March 2023, the Russian president-for-life had even became the subject of an international manhunt,, wanted on suspicion of organizing the mass deportations of Ukrainian children from the territories Russian forces still illegally occupied. Perhaps Min Aung Hlaing could not elevate his status sufficiently to become an equal of the Russian leader, but Putin nevertheless managed to diminish his own standing to the extent that the head of the junta became a dear guest for him.

Putin managed to diminish his own to the extent that the leader of the junta became a dear guest for him

The two finally met at the Eastern Economic Forum in September 2022 in Vladivostok. Officially, the conversation between the pair of usurpers revolved around democracy. Following this exchange of ideas, the Russian side even undertook the commitment to assist the Asian junta in its efforts to conduct future elections, a fact reported by Myanmar's official media without any hint of irony.

As for the unofficial discussions between representatives of the two regimes, one can infer their contents from subsequent events.

By the fall of 2022, even Vladimir Putin understood that the war against Ukraine would not end quickly or easily. Perhaps he even warned the general that, due to immense amounts of Russian military equipment being destroyed by the Ukrainian army, Moscow would be forced to cut back on its military cooperation with Myanmar, which had only increased since the latest coup. Between the overthrow of Aung San Suu Kyi's government on February 2, 2021, and the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the Kremlin supplied weaponry and military equipment to Myanmar worth a whopping $276 million. For comparison, China’s military contracts with Myanmar over the same period totaled only $156 million.

At the time of their meeting in the Russian Far East, however, it is plausible that Putin was already beginning to agitate for the return of some of the Russian military hardware that had been sold to the junta over the years. In any case, the existence of such an initiative came to light very soon thereafter. Faced with mounting battlefield losses and an inability to evade international sanctions sufficiently to modernize many of the tanks and armored vehicles it still had in storage, Russia began buying back some of the matériel it had previously exported to Asian countries.

In June 2023, the Japanese publication Nikkei reported that Russia had paid India $150,000 in order to buy back Russian-made guidance systems for anti-aircraft missile complexes. The first known re-export sale occurred in August 2022, one month before the Vladivostok meeting between Putin and Min Aung Hlaing.

The Russians repurchased thousands of tank sights, which they themselves had previously supplied to Myanmar

By December 2022, Russia was already on its way towards buying back at least $24 million worth of tank sights that had previously been exported to Myanmar. Notably, the components were sent back to the same enterprise from which they had initially been exported — Uralvagonzavod, home to warehouses that store thousands of old tanks capable of returning to service after modernization.

Moscow’s military buyback spree could not be kept in secret for long. In March of last year, the Ukrainian Chief of the Main Directorate of Military Intelligence, Kirill Budanov, started making public claims that Russia was attempting to make up for ammunition shortages by turning to third countries. Among the trading partners Moscow was negotiating with, Budanov said, was Myanmar.

While the junta denied that such talks had even taken place — arguing that it is Russia, not Myanmar, that is one of the world's largest arms producers — the generals claim seems highly dubious. By the time of Budanov's statement, Russia had been already been bombing Ukrainian civilian infrastructure for several months with Iranian kamikaze drones and had also reached an agreement with North Korea to purchase artillery shells. In fact, just a few months after Budanov's statement, the first mortar shells from Myanmar were “exposed“ in videos captured by Russian forces themselves located somewhere along the front line in Ukraine.

These deliveries were occurring — and, for all we know, have continued — against the backdrop of the escalating civil war in Myanmar, where the junta's forces do not always enjoy the advantage. Why the generals proved so willing to part with scarce military resources remains a question without a clear answer. But, then, anyone who has followed the decisions of the Russian regime over the past two years likely already understands that a junta like the one in Southeast Asia is fully capable of acting to the detriment of its own side’s interests on the battlefield.